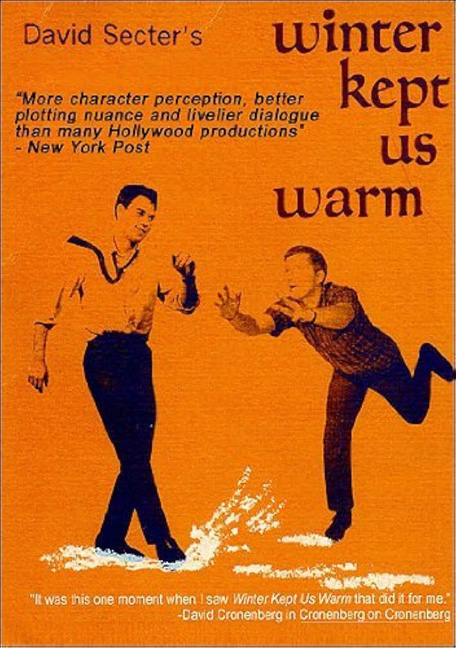

It’s 1965, and a twenty-two-year-old student at the University of Toronto, David Secter writes, directs and funds a ground-breaking feature film, Winter Kept Us Warm (1965).

A gay-themed independent movie, it was covered by influential film journals, including Sight and Sound and Cahiers du Cinéma, and featured in mainstream publications such as Variety and the New York Times. It became the first English-Canadian movie ever screened at the Cannes Film Festival, and is widely considered a key milestone in the development of the Canadian film industry.

In 1975, ten years after making such an impact, Secter was in a communal-living, clothing-optional, sex-positive, drug-friendly, interior-decorating, urban-renewal, film-making, kibbutz-family of thirty young people in the lower East Side of New York, and making a pornographic film, Blowdry.

The Rialto Report tracked down David Secter to find out what happened.

With special thanks to David Secter, Joel Secter, Joey Asaro, Bob Foreman at Vintage Theater Classics and Allan Tannenbaum.

———————————————————————————————————-

1. Total Impact

In 1971, after having made two films in Canada, David Secter left his home country and moved to New York to pursue his filmmaking career.

How did a movie director from Canada, who’d made a pair of successful, critically-acclaimed films, end up in New York in 1971?

‘Winter Kept Us Warm’ had been a hit in New York where it played for six weeks. As a result, I was signed up by the New York office of the William Morris Agency. There was no real film industry in Canada in the 1960s, so I had to leave if I wanted to make movies, and I liked the idea of living in New York.

Had you been to New York before you moved there?

Yes, in 1969. I wrote the book and lyrics for an off-Broadway musical called ‘Get Thee to Canterbury’ which was based on Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’. It played at the Sheridan Square Playhouse in January and February 1969.

How did the William Morris deal work out?

I was asked to direct Cher’s 1969 film ‘Chastity’, but that fell through.

Then they lined me up to direct something in Spain called ‘The Fly Girls’ for Cinemation – who’d had big success with films like ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss’ Song (1971), ‘Johnny Got His Gun’ (1970), and ‘Female Animal (1970)’ – but that didn’t happen either.

But by that stage, I wanted to try something completely different.

Which was what?

I’d started living at 231–235 Second Avenue at 14th Street in the Lower East Side of New York. It was a beautiful, big five‐story walk‐up building with about 35 apartments.

I fantasized about creating a film commune of artists who owned their own production company, a cooperative group that would share each other’s talents and… each other.

I found other people who liked the idea, so we formed Total Impact.

What did you see as the benefits of making films in this way?

For a start, it would integrate filmmaking with a whole different way of living. It was a utopian vision for the future – an alternative way to make movies as well as an alternative solution to living.

Plus, I thought we could make films in a more cost-effective way.

How did you get everyone to live together in the same building?

After I moved in, I saw that the landlord needed a new superintendent for the building, so I suggested that our new group take over the maintenance duties – plumbing, water, electrics, everything. The landlord liked the idea, and in return, he gave us a break on the rent.

That meant that we were the first to know when apartments came available, so pretty quickly we had everyone living together in the building.

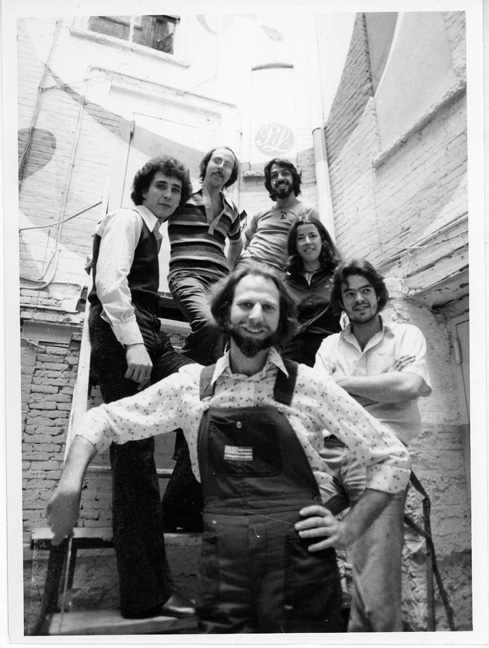

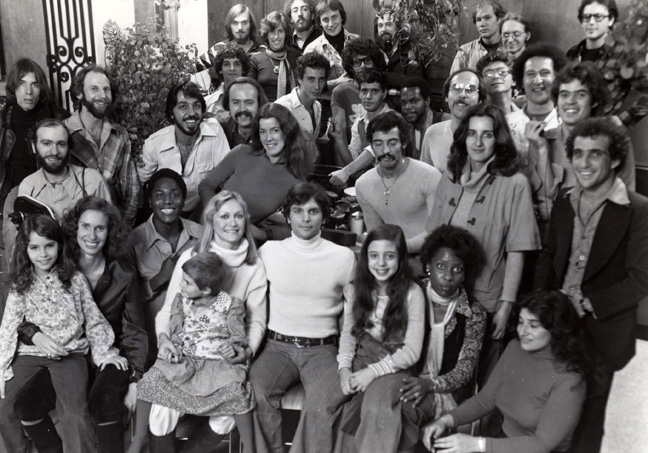

How many people were part of the group?

Around 25-30 at any stage.

The key members were Avery Klauber, Joey Asaro, Sam Kitt, and Ted Hammer.

Joey Asaro, in the 2nd Avenue commune building

Joey Asaro, in the 2nd Avenue commune building

What kind of person joined the commune?

It was a mix: some were attracted by the group filmmaking; others liked the idea of communal living. They were young people, mostly in their 20s and 30s.

How did the commune work?

Everyone had an equal share in the collective, so everything was jointly owned – such as the apartment leases – and no one received a salary. We pooled everything and shared it together.

We’d take turns to cook meals and clean the place, and we all lived and worked in the same space.

How about the personal relationship part of living together?

I was personally involved with men and women at that time and I wanted a solution which allowed us multiple relationships – combined with making movies. It would be a media group marriage.

The idea was that there would be no boundaries. I was getting people together that I thought would be together forever.

Can you tell me about the physical space?

There were two apartments on the ground floor which we used for the main office and the commissary. Then we had seven or eight other apartments in which we lived and used for our communal dining room and storage for our equipment, props, and clothes.

Before we arrived, the basement had been used by junkies as a shooting gallery so it was like an urban renewal project as well. We turned it into a screening room, an editing room, a recording studio, laundry, a lounge area…

There was a dark courtyard in the center of the building which we used a lot – we painted it to brighten it up – and the building had a roof garden too.

It was like a mini-Hollywood studio!

Roof garden at the 2nd Avenue commune building

Roof garden at the 2nd Avenue commune building

How did Total Impact work as a business?

Money was always the biggest problem, so we had to take side jobs to keep the whole thing afloat.

Film jobs?

Some were film-related. For example, we shot commercials and industrials. We did a commercial for the Guinness World Record Museum in the Empire State Building – and we won a National Clio award as one of the best commercials of the year.

Other times we did completely different work: for example, we had two trucks so we had a moving service. We also had a contract to deliver the Soho Weekly News every week, which was a local New York newspaper.

How did the communal living ideal work in practice?

The concept of a group marriage seemed like a good idea, but some people dealt with it better than others. So it had its ups and downs – as you would expect from any group of 25 people living together. There were a lot of happy moments as well as a fair amount of drama and volatility too.

It’s strange, as it was my concept and idea, but with hindsight I don’t think I was well suited to living with other people. I hadn’t had many close relationships with people, and then suddenly I was in a relationship with… all these people. For some people it worked well – they played board games, watched films, and did group activities. I wasn’t really interested in all that.

How did other people in the building react to Total Impact?

We were good for the building because we took care of any problems immediately, so in that respect we were popular and well-liked. Phillip Glass, the composer, was one of the residents in an apartment upstairs.

Sometimes, when we were shooting in the building – and we did a lot of that – it created difficulties.

*

2. ‘Getting Together’ (1976)

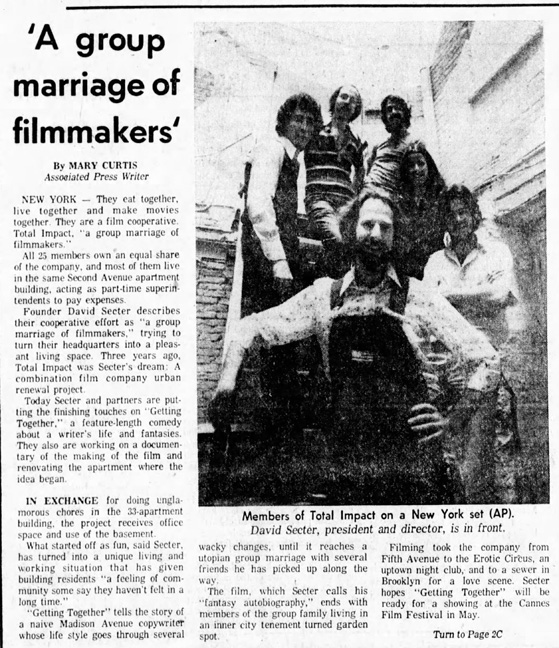

With Total Impact established as a film-making collective group, attention turned to actually making movies.

How did you decide what films Total Impact was going to make?

We decided that our first venture would be a comedy, Getting Together, which would parallel the real-life communal living collective that we had on 2nd Ave. I called it a ‘fantasy autobiography’. And the second film would be a documentary about the making of the first.

So the fictional film would be based on your real life, and the second film would be a real-life account of the making of the fictional film?!

Yes! And we shot both of them in our apartment building, so the basement, the courtyard, and the apartments that we lived and worked in all feature in both films.

Documentary footage shot by Total Impact

Documentary footage shot by Total Impact

From the New York Times (1975):

Total Impact is a communal enterprise: it is organized somewhat differently from its highly individualistic forebears, but is scarcely less diversified than its monster‐sized competitors.

“We may be the first janitors ever to win an Oscar,” said Avery Klauber, the 28-year‐old production manager of the three‐year‐old organization.

What was the budget for the two films?

At first it was $25,000, but we had endless delays because it took years to make both films.

Why was that?

The script went through endless re-writes which reflected the ups and downs of the communal situation. It took so long that our money reserves – which were never that good – started to run very low.

Were drugs an issue as well?

Not so much an issue, but it’s true that we were high a lot of the time.

David Secter directs, in documentary footage shot by Total Impact

David Secter directs, in documentary footage shot by Total Impact

*

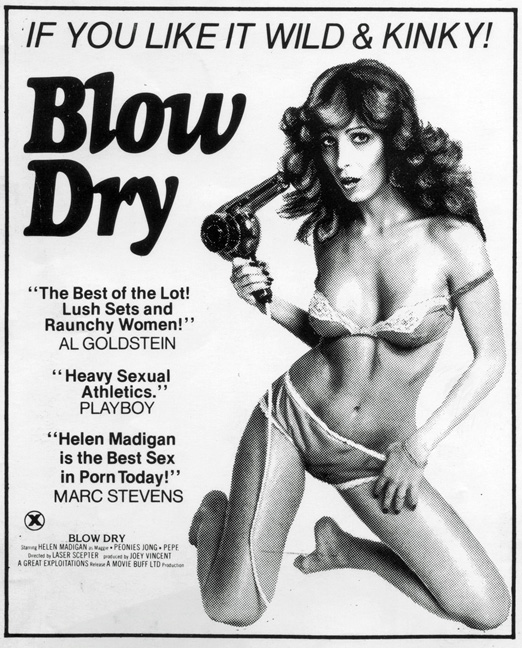

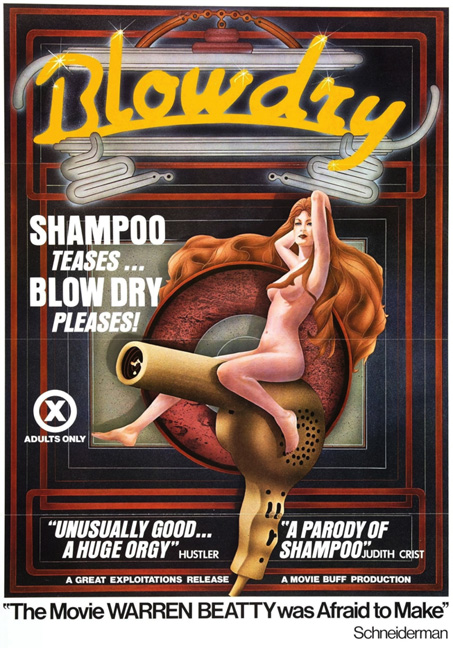

3. ‘Blowdry’ (1976)

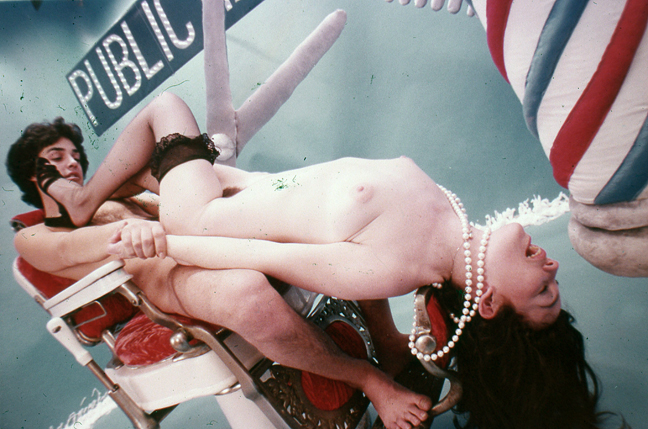

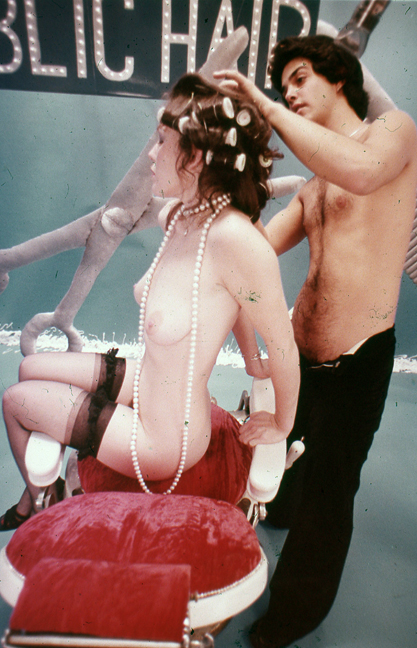

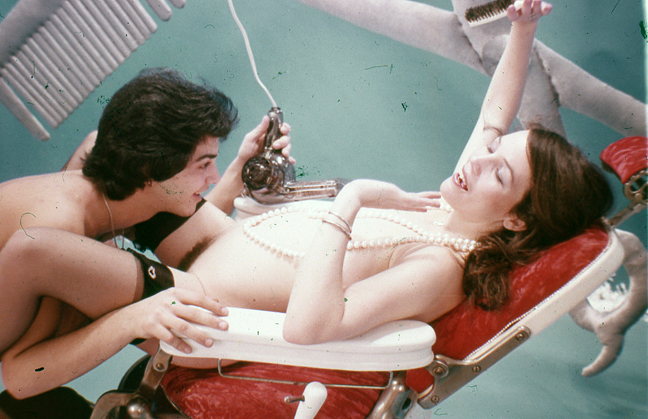

After several years of struggling to finish ‘Getting Together’ and the documentary, the Total Impact collective decided to make a third film: an X-rated sex movie, ‘Blowdry’.

Where did the idea to make a pornographic film come from?

It was a get-rich idea to keep working on ‘Getting Together’ – and to keep Total Impact alive.

Where did the money for it come from?

We all invested everything we had in it. My family invested in it as well. They came down to Canada to give us the money.

Had you seen any adult films before then?

Not really. I might have seen Deep Throat (1972) and Devil in Miss Jones (1973), but I wasn’t an aficionado. If I’d had any interest, I would’ve gone to see gay porn, but no, I didn’t know much about adult films.

So we all went to theaters to see some examples, and we tried to find the ones that were at the upper end of the quality spectrum.

And who was the creative force behind ‘Blowdry’?

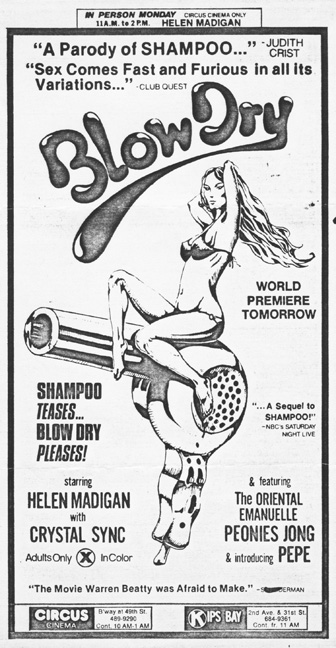

Sam Kitt had just seen Hal Ashby’s ‘Shampoo’ which starred Warren Beatty, and so he wrote a script which was a parody.

You hired many well know performers on the adult film scene, including Helen Madigan, Pepe, Jamie Gillis, Ultramax, Crystal Sync, Robert Kerman, and Michael Gaunt. How did you go about finding them?

Someone put us in touch with Jamie and Robert Kerman. Jamie brought in Helen and Pepe, and Robert brought in two acting friends, Crystal Sync and Michael Gaunt.

We wanted to hire an actress named Bree Anthony for the main role, but she was too expensive, so we went with cheaper options…

What was your experience like working with them?

They were fun. I liked Pepe Valentine who was the lead actor. He was able to sing a song for the movie because he was in a band at the time.

The strange thing was that we hired Jamie Gillis – who was a well-known name who we cast as a gay hairdresser – and he didn’t have sex at any stage in the film.

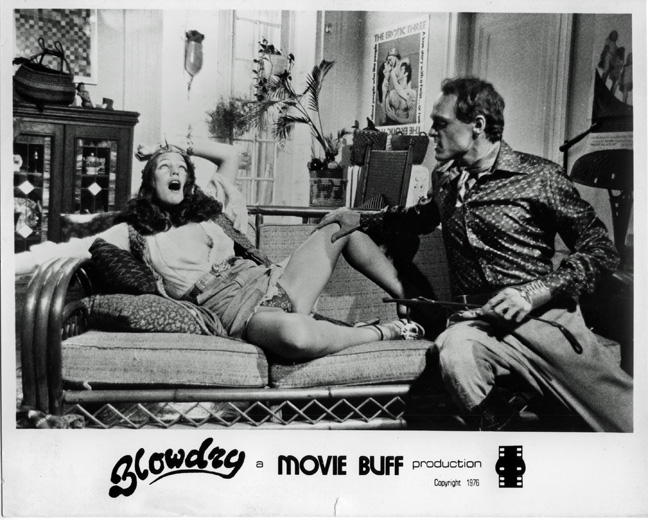

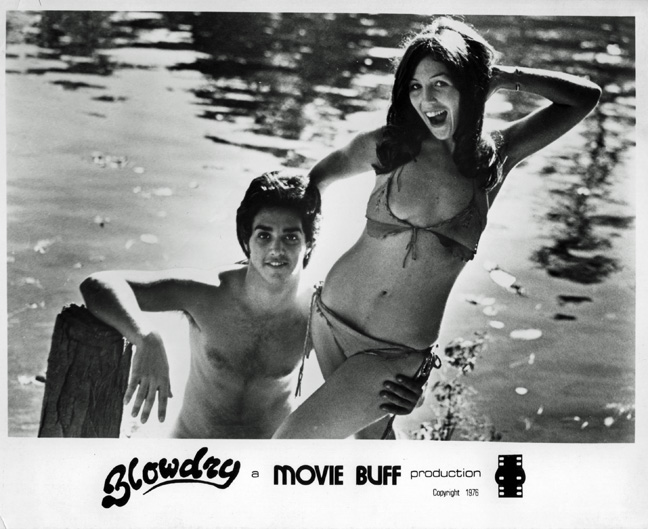

Pepe Valentine and Helen Madigan in ‘Blowdry’

Pepe Valentine and Helen Madigan in ‘Blowdry’

You used the name ‘Laser Scepter’ as the director…

Yes, Laser was the name of my great grandfather, and I thought that ‘Laser Scepter’ sounded magical, as well as a good porno name!

Was ‘Blowdry’ shot in the commune building?

Yes – mostly. We created sets there, and also shot in the basement, on the roof, and in the courtyard.

The two exceptions were the hair salon where we rented a real salon. And then there was the big country house where the film ends in an orgy. That cost us a lot – and of course, we didn’t tell the owners what we were shooting.

Did ‘Blowdry’ suffer from the same sort of delays that affect the other two films you were making?

No – it was a smooth production, and it was fun to make.

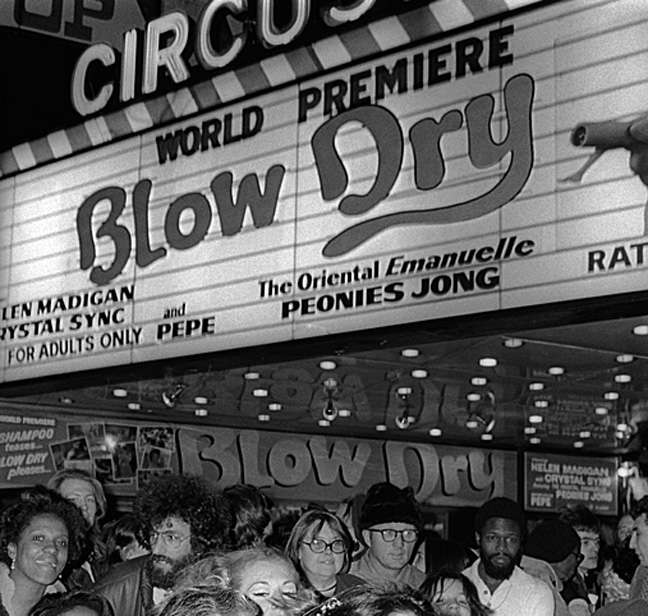

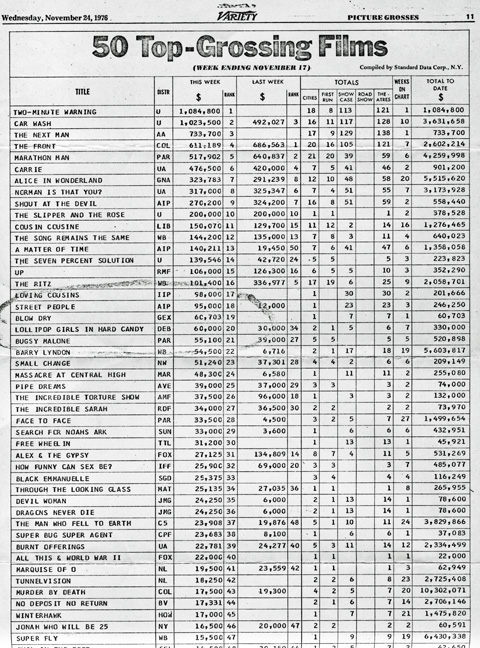

‘Blowdry’ premiered on November 8, 1976: what do remember about that event?

It was worthy of a Hollywood premiere! It was a black-tie affair, and everyone involved came along. We hired a restaurant to have a big party afterwards – and we filmed everything of course.

Blowdry taglines:

Shampoo teases… Blow Dry pleases!

She’s Coming To Blow You Away!

Pepe Valentine, at ‘Blowdry’ premiere

Pepe Valentine, at ‘Blowdry’ premiere

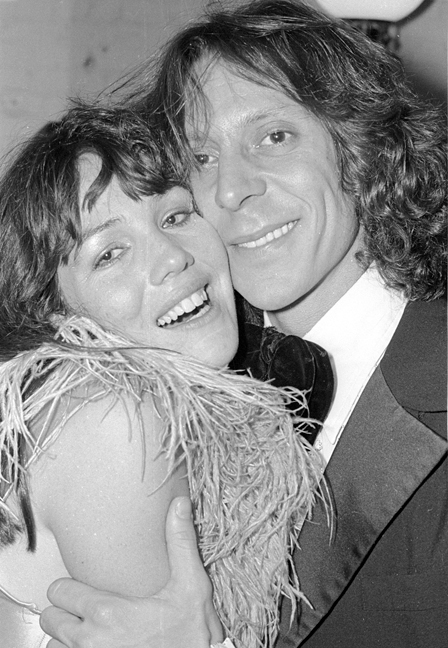

Helen Madigan and Marc Stevens, at ‘Blowdry’ premiere

Helen Madigan and Marc Stevens, at ‘Blowdry’ premiere

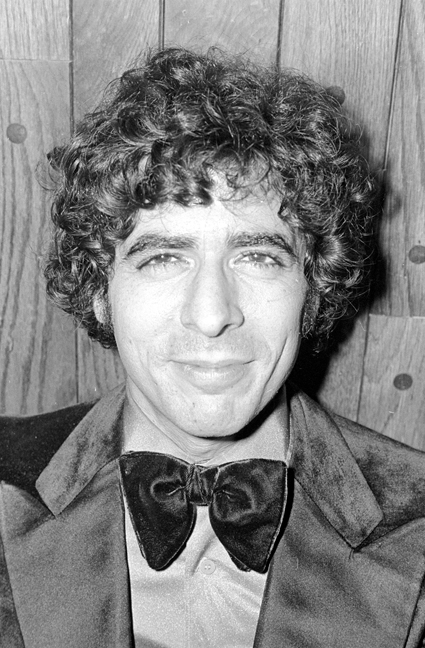

Jamie Gillis, at ‘Blowdry’ premiere

Jamie Gillis, at ‘Blowdry’ premiere

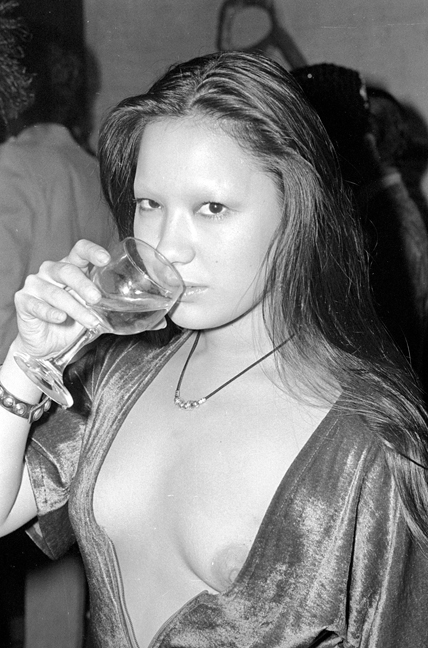

Ming Toy, at ‘Blowdry’ premiere

Ming Toy, at ‘Blowdry’ premiere

David Secter (center) interviews Helen Madgian and Pepe Valentine at Blowdry premiere, documentary footage shot by Total Impact

David Secter (center) interviews Helen Madgian and Pepe Valentine at Blowdry premiere, documentary footage shot by Total Impact

How was ‘Blowdry’ distributed?

We hoped that the big premiere would get some distributors interested, but… nothing. So Sam Kitt took on the distribution. He did a good job, and ironically, that really launched his career. He went on to work for Universal, and then he headed up Spike Lee’s Los Angeles production office. He’s done very well as a result of ‘Blowdry’!

And did the film make money for you?

It got good reviews and did ok, but it didn’t make a lot of money.

*

4. ‘Feeling Up!’ (1976)

The additional money from ‘Blowdry’ enabled the Total Impact collective to complete ‘Getting Together’. The next problem was selling it.

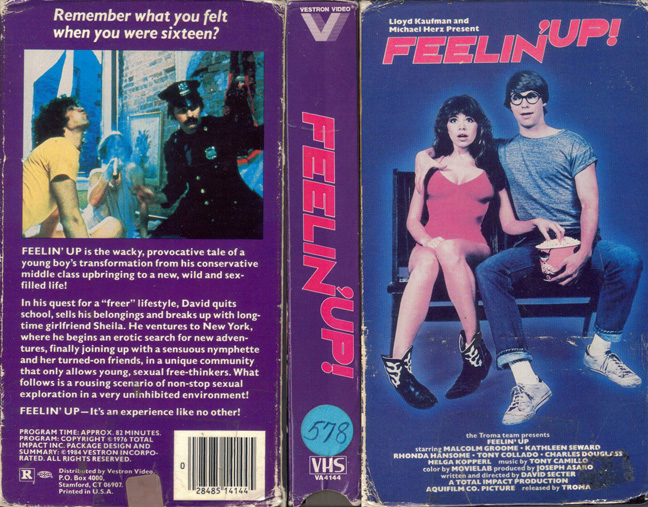

How did ‘Getting Together’ get released?

We eventually made a deal with Troma. The problem was that that they made significant cuts to the film, and put it out as a teen sex comedy with the title ‘Feelin’ Up!’

What scenes did Troma cut?

Two lengthy scenes: one was a bicycle scene where the actors ended up in a bathhouse in the Village, and a scene that we shot in St Mark’s church – which had some flagellation.

What was the effect of the cuts?

It ruined the film, and didn’t make it any more successful.

David Secter directs cut scene from ‘Getting Together’

David Secter directs cut scene from ‘Getting Together’

What happened to the original version?

I wish I knew. I’d love for it to be restored. The original was a good film and I’m still convinced it would find an audience – even today.

I had a 3/4-inch tape of it that I lost over the years after moving house. But I live in hope that the original will still be found.

And what happened to the documentary that you’d been making from the beginning – and all the footage of the commune living and working that you shot?

It all survived: it’s with my nephew who made a documentary about me 25 years ago. We never made the documentary sadly, so that film never got made.

*

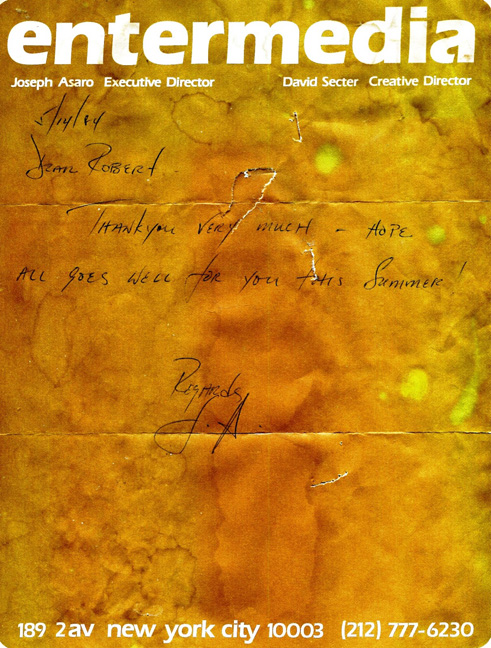

5. Entermedia

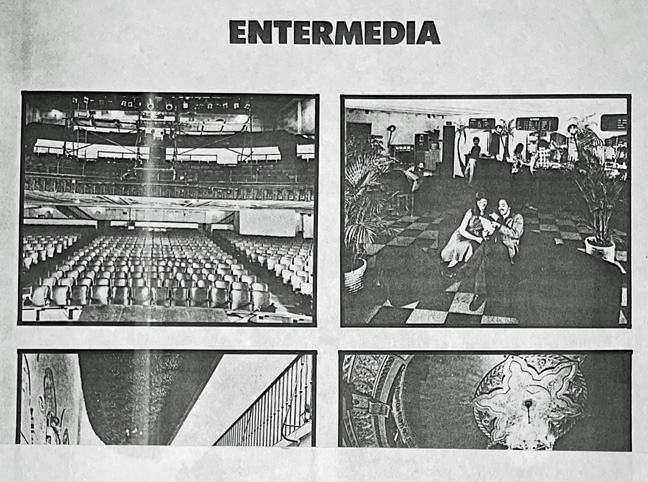

In 1977, Total Impact changed strategy and took over an East Village movie theater, the 12th Street Cinema, which it renamed the Entermedia Theatre.

Why did you change direction and decide to take over a theater?

The movies we made hadn’t earned enough money to support the collective, so we needed a different direction. We formed a new group called Entermedia, which was mostly comprised of the Total Impact collective.

What did you know about the 12th Street Cinema?

It had been the local neighborhood theater for the previous 70, 80 years near where we lived. In the 1960s it was the Casino East Theatre, which was mainly a burlesque establishment, and then in 1965, it became a burlesque house called the Gayety Theatre. In 1969, it changed into the off-Broadway Eden Theatre which presented the musical, ‘Oh! Calcutta!’

How big was the theater?

1,200 seats.

How did you convince the landlord that you could take such a big establishment over? After all, you didn’t have much money…

What we had was Total Impact: a group of hard-working people who were willing to take responsibility for a big space, and totally revive and transform it – just like we had done with our apartment building.

But a theater is rather different proposition…

We convinced the landlord that we could turn it into an arts center, and he liked that. For example, there were two lofts which we turned into small theaters. We put on a production of ‘Hess’ starring Michael Burrell – that won an Obie award.

What was the state of the theater when you took it over?

Terrible! We had a lot of work to do to refurbish it. We took furniture donations from local businesses, and it turned out well.

And everyone in Total Impact took part in the renovation?

Yes, we did everything together.

It was however the beginning of the end of the collective. People still stayed in our building but one by one, they took their own leases, and so the vision of us all being one family broke apart.

Entermedia were also involved in music production and the theater saw concerts by the likes of Talking Heads and the Stranglers.

How did your involvement with the theater end?

The landlord got an offer from a movie theater chain to convert it into a multiplex cinema. We couldn’t compete with that… so we had to give it up.

After closing in 1988, the theater became the Village East Cinema. Angelika rebranded the theater in 2021.

*

6. After New York

After Entermedia Theater was sold and the Total Impact collective group came to an end, David left New York and moved to Los Angeles in 1989, where he lived in Long Beach with his partner Patrick. In 1997, he made his next film Cyberdorm.

In 2005, David directed and released a documentary film on the Gay Games, titled Take the Flame! Gay Games: Grace, Grit, and Glory.

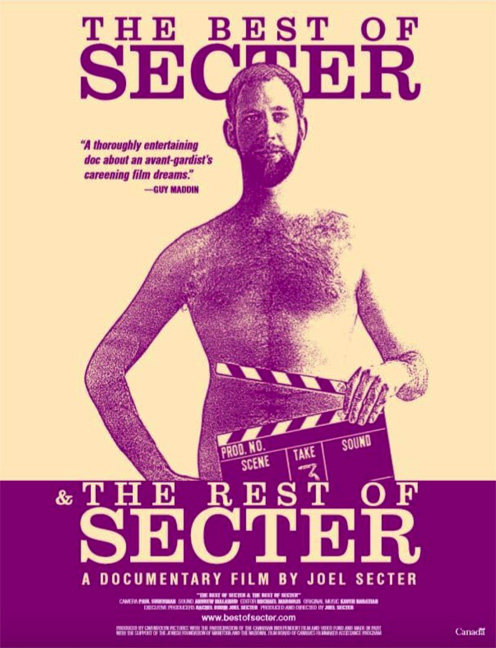

In 2005, David’s nephew, Joel Secter produced a Canadian documentary about his uncle titled The Best of Secter & the Rest of Secter, featuring interviews with many of those involved in Total Impact, and also filmmaker David Cronenberg and composer Philip Glass. The film contains some of the documentary footage that Total Impact shot back in the 1970s.

Today David lives in Kona on the Big Island of Hawaii with his husband Patrick Montana, where he is completing the book and lyrics for Rule of Fire: A New Musical In Old Hawaii, collaborating with Nashville-based composer Ruben Estevez.

*

*

A first class story and an excellent interview from the always brilliant Rialto Report.

This is a beautiful rise and fall of an ideal, perfectly told.

Nobody does it better, as someone else once said.

The pictures and artifacts are staggering. This film was made almost 50 years ago, and yet the high quality of the written content is enhanced by the images you have uncovered.

This site is a true gem.

Thank you for what you do.

thanks so much for the archives and appreciation of all of the work! My dad would be happy to see it all on lives on in a way.

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work

Don’t have the words, RR, but floored as always.

Happy New Year, Rialto Report. May 2025 be your best yet.

Fantastic History. You have done it again, Rialto!

Amazing history of this film and collective. So thankful we used to have artists willing to take such chances.