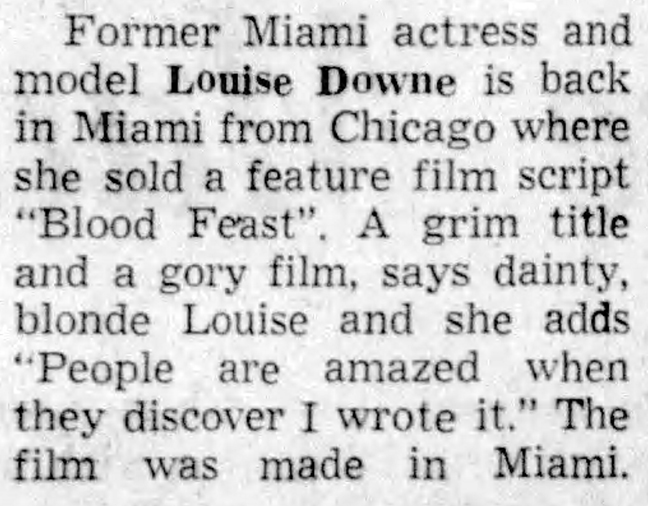

Last week, we concluded our series on the impact of Cuban immigrants on the Florida exploitation films industry in the 1960s and 1970s. One of the peripheral characters in the wider story was Louise ‘Bunny’ Downe, a model and actor, who went on to be an important figure behind the scenes in the films of Herschell Gordon Lewis, the so-called ‘Godfather of Gore.’

This week, we feature a guest essay from Janna Jones that analyzes the life and career of Downe. In addition to writing this article, Janna has also written a screenplay loosely based on Downe’s life and work, called ‘Cheap, Sexy and Shocking,’ which has won 30 screenwriting awards — including awards from Paris, London, Sydney, New York, San Francisco, Montreal, and Hollywood.

Janna Jones is a professor of Creative Media and Film in the school of Communication at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona. She is the author of the books ‘The Southern Movie Palace: Rise, Fall, and Resurrection’ (University Press of Florida); ‘The Past is a Moving Picture: Preserving the Twentieth Century on Film’ (University Press of Florida) and ‘The Spirit of the City: Marshall Fredericks Sculptures in Detroit’ (Michigan State University Press). She has also published many essays and book chapters about film, architecture, design, and preservation which include articles in the Journal of Curatorial Studies, Liminalities, The Moving Image, and the Michigan Historical Review. In addition to her books, she has won more than 300 awards for her feature and short screenplays.

We are indebted and grateful to Janna for allowing us to present this essay in a public forum for the first time.

*

Janna Jones writes:

Louise Downe played a significant role in the exploitation cinema movement in the 1960s and early 1970s, and her take on abortion in particular was forward thinking and is extremely timely. Her contributions as an actor, screenwriter, assistant director, and designer are a noteworthy chapter in twentieth century cinema history. Her efforts have been routinely overlooked, as she has been overshadowed by her moviemaking partner, Herschell Gordon Lewis.

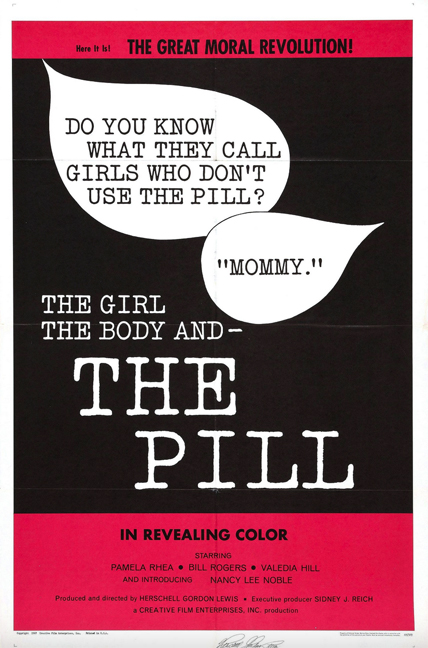

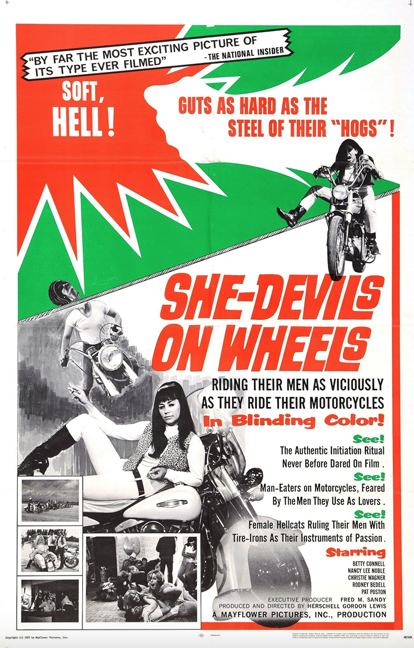

This essay details her early years living in Miami and explains her work as an actor in nudie-cutie movies and her role as an assistant director and designer in a variety of exploitation movies. I then analyze some of her contributions as a screenwriter by analyzing two ground breaking exploitation movies that she wrote: The Girl, the Body and the Pill (1967) and She-Devils on Wheels (1968). Working within the constraints of the low budget exploitation movie genre, Downe manages to shift two significant boundaries directly related to women’s bodies on the cinematic screen, and for this alone, her work is important.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Louise Downe – Introduction

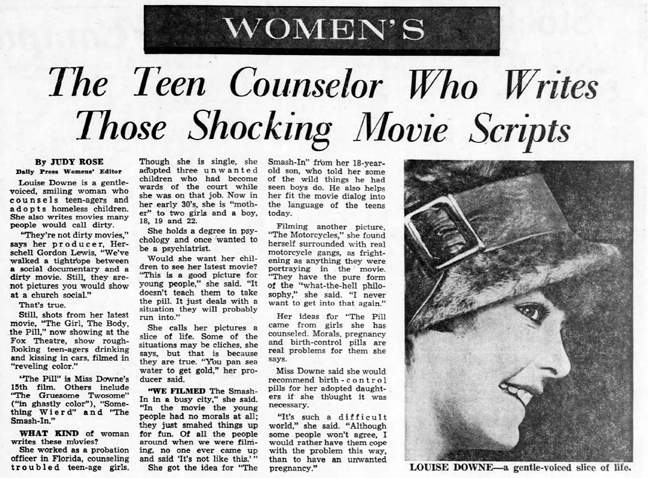

Researching Detroit’s Fox Theatre, the city’s premiere picture palace, I stumbled upon a 1968 article in the Women’s section of the Detroit Free Press. The headline read ‘The Teen Counselor Who Wrote Those Shocking Movie Scripts,’ and accompanying the article was a photo of a stylish young woman wearing a charming hat. The young woman in the photo was a screenwriter whose recent exploitation movie, The Girl, the Body, and the Pill was showing at the Fox Theatre. Exploitation movies, low budget, B-movies that contain sexual, violent or gory content, helped picture palaces, like the Fox Theatre, from closing their doors in the 1960s and 1970s. Most of the young adult fans of racy, low budget exploitation movies were not concerned with the deteriorating conditions of the theaters, nor were they afraid to go downtown after dark.

In the article, Louise Downe, the screenwriter of ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ is described as a “gentle-voiced, smiling woman who counsels teenagers and adopts homeless children.” The article also explains that “She also writes movies many people would call dirty.”[1] Her producer, who is also quoted in the article, is none other than Herschell Gordon Lewis, a pioneer of gore and exploitation cinema. “We’ve walked a tightrope between a social documentary and a dirty movie,” Lewis states in the article. “Still, they are not pictures you would show at a church social.”[2] Lewis is a well-known and celebrated figure of exploitation cinema, but Downe, who worked with Lewis for over a decade, has gone unnoticed and her contributions to the exploitation movement barely have been recognized. Because Downe and her movie making efforts have been overlooked and little has been written about her, I begin this essay by detailing her early years living in Miami and explaining her role as an actor in nudie-cutie movies and her role as an assistant director and designer in a variety of exploitation movies during the 1960s. I then analyze some of her contributions as a screenwriter by analyzing two ground breaking exploitation movies that she wrote: ‘The Girl, the Body and the Pill’ (1967) and She-Devils on Wheels (1968). Both of these movies challenge long held views of women’s bodies on the screen that had been in place since the beginning of the motion pictures. ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’, a progressive movie that promotes sex education in high schools and advocates for the use of birth control pills, portrays one of the first abortions ever shown on screen in the United States. ‘She Devils on Wheels’ though not particularly progressive, is a women-centered movie partly focused on women’s sexual desires. It realigns cinematic boundaries of gender by simply omitting men altogether for nearly the first twenty minutes of the movie. When men do appear, they are mostly objectified and treated as secondary characters that have little to no influence or consequence. Working within the constraints of the low budget exploitation movie genre, Downe manages to shift two significant boundaries directly related to women’s bodies, and for this alone, her work is important. Her contributions as an actor, screenwriter, assistant director, and designer are a noteworthy chapter in twentieth century American cinema history.

*

Growing up in Miami

Alma Louise Downe was born in Miami on August 12, 1937. Her parents, Hector Downe Schlossberg and Alma Louise Hamby did not stay together for long, and Downe spent most of her childhood and young adulthood in Miami, living with her mom. Through the years, Downe also went by Allison Downe, Bunny Downe, Bunny Downs, Bonnie Downe, Alma Hamby, Alma Mertz, Alma Thorne, Vicki Miles, and Vickie Miles, but she went mostly by Alma as a young girl.[3] A 1941 Miami Herald Sun article about her mother explains that Mrs. Downe had recently returned to Miami after a decade away. The accompanying photo shows Mrs. Downe with her young daughter “Alma Louise” who was four at the time. The article states that Mrs. Downe, who was once Alma Hamby, is a painter and had lived in Panama and New York since leaving Miami.[4]

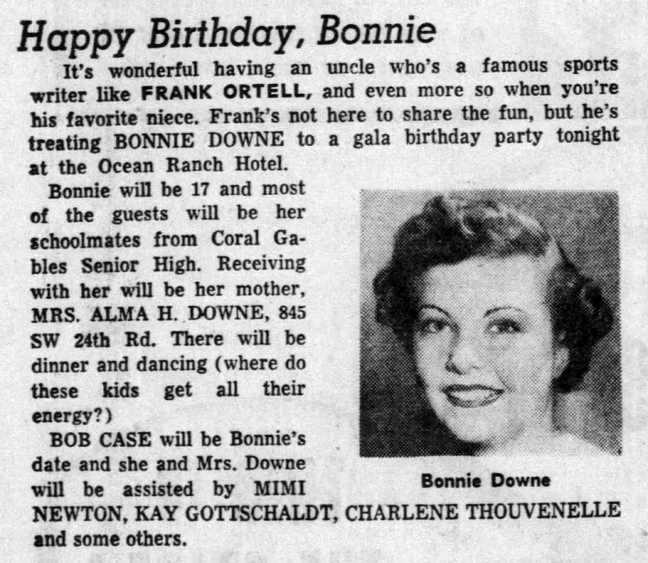

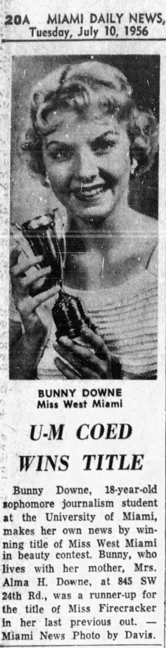

Downe went to Shenandoah Junior High in Miami where she was involved in the Red Cross and speech contests.[5] [6] She then attended high school at Coral Gables High, where she maintained her interest in the Red Cross.[7] When in high school, Downe was also called Bunny and Bonnie.[8] In 1955, she graduated from Coral Gables High School and enrolled in the University of Miami. There she became a member of the Delta Zeta sorority.[9] In her sophomore year at the University of Miami, Downe won the Miss West Miami Beauty Contest and was runner up in the Miss Firecracker contest.[10] She also competed for the Miss Miami title, but did not win the contest. [11] By 1957, Downe was a model and owned her own modeling agency.[12] In 1957, she eloped with her first husband, Lewis Mertz, who was also a student at the University of Miami.[13] Their marriage was short-lived as they divorced in 1959. Seven months later, she married her second husband Petrie L. Thorne who was a student at the University of Miami. In their wedding announcement in The Miami Herald, it states that Downe, who was using the name Louise, had won 25 beauty titles and had attended the University of Miami.[14]

*

Downe’s Acting Career

By July 1960, her second marriage appeared to be in trouble. In an article in The Miami News, Downe (who was going by Bunny once again) was acting in a movie entitled Naked Island and was reportedly living at the Gold Dust Motel. “I have gotten a lot of experience,” Downe explained, “and have met some terrific people, among them Sepy Dobronyi, over whom I have flipped.” Dobronyi was a Hungarian-American sculptor who, according to his obituary was “an unrepentant playboy” and was “Miami’s Hugh Hefner.” Downe’s feelings for Dobronyi most likely helped to end her marriage, and Thorne and she were divorced in December of 1960. The movie ‘Naked Island’ which was released in 1961 (as Pagan Island ) is a story about a shipwrecked sailor who lands on an island inhabited by topless women (their breasts are covered by leis). Downe, plays Malia, one of the topless maidens and goes by the name ‘Bunny Downs’ in the movie’s credits. Directed by Barry Mahon, Downe would go on to act for him on three other movies: Bunny Yeager’s Nude Camera (1963), International Smorgas-Broad (1965), and the iconic The Beast that Killed Women (1965).

Bunny Downe (far right), Pagan Island (1961)

Bunny Downe (far right), Pagan Island (1961)

Between 1961 and 1965, Downe acted in 13 movies; most of them were nudie-cuties. As the name suggests, nudie-cuties are low budget movies that feature nude young women in humorous and generally non-sexual situations. Of the 13 movies Downe acted in, sans clothing, five of them took place at a nudist camp, a common setting for nudie-cuties. Low budget filmmakers took advantage of a 1957 court ruling that deemed movies about nudist colonies to be educational. On July 3, 1957, Judge Charles Desmond in the Court of Appeals of the State of New York issued a landmark ruling that nudity, per se, was not indecent. He wrote, “There is nothing sexy or suggestive about it… nudists are shown as wholesome, happy people in family groups practicing their sincere but misguided theory that clothing, when climate does not require it, is deleterious to mental health by promoting an attitude of shame with regard to natural attributes and functions of the body.”[15]

Downe’s first starring role in a movie, the 1962 nudie-cutie, Nature’s Playmates, which was mostly shot at the Tropical Gardens nudist camp in Miami. It was also her first time acting under Lewis’ direction (he is called Lewis H. Gordon in the credits). Downe plays Diana Scott, a private investigator who works with her boss, Russell Harper (Scott Osborne) in Chicago. The movie, narrated by the sensible and attractive Diana Scott, begins in their office where a client asks for their help locating her husband, who she suspects is living in a nudist camp in Miami. Russell Harper and Diana Scott agree to take the case, and in the next scene, we see Diana Scott shopping for clothes for her trip to Miami Beach. She walks out of five clothing stores (that look like they are in Miami rather than Chicago) with her arms full of boxes. Diana Scott, aka Louise Downe, certainly looks like a fashion model. She is a tall, thin, blonde who looks elegant in a white dress and heels. After she and her boss arrive in Miami, they rent a red convertible, and we are afforded a tour of Miami, as they drive with the top down. Finally, they reach a nudist camp, the place where they suspect their client’s husband is living.

Naturally, Diana Scott and Russell Harper must be nude to be amongst the people at the nudist camp. After she checks in to her well-appointed room, we watch Diana Scott hesitantly but gracefully take her clothes off–for a full five minutes. Her high heels are the last item she takes off before she goes outside to meet Russell Harper, who is also sans clothing (we see nothing below his waist). Diana Scott and Russell Harper tour the camp, looking for their client’s husband, but they cannot find him, so they put their clothes back on and jump into the red convertible to find another nudist camp, Paradise Gardens. Diana Scott and Russell Harper check in, and the concierge lets them know there this is going to be a twist contest.

Diana Scott gets ready for the dance contest by taking a shower—of which we are privy to, and then she takes off for the contest, while her partner goes searching for evidence of their client’s husband. When the arm goes down on the record player, and the music for the contest begins, we see a dozen or so people, in the nude, begin dancing the twist for two minutes. As one can imagine, the camera focused mostly on Dianna Scott’s and other young blondes’ breasts. When the dance was finished, a young man escorted Dianna Scott around the grounds. We see nude young women and a young boy taking turns jumping on a trampoline, nude men playing chess, and a group of nude volleyball players playing in a pond, and a group of nude folks swimming and sunbathing by a pool, and a young woman taking an outdoor shower.

Finally, Dianna Scott and Russell Harper find their client’s husband, Mr. Elliot—who does not wish to return home to his wife. Dianna Scott calls her and convinces her to come to Miami to the nudist camp to see her husband. Mrs. Elliot comes Miami. She takes off her clothing at the nudist camp, and discovers she likes be a nudist, and she and her husband happily reunite. When Russell Harper commends Dianna Scott for her great PI work, she tells him she is quitting the job because she will be getting married. They walk off arm in arm, as apparently working on the case at the nudist camp helped foster their love for one another.

Bunny Downe in ‘Nature’s Playmates’ (1962)

Bunny Downe in ‘Nature’s Playmates’ (1962)

*

Herschell Gordon Lewis and Louise Downe’s Work Together

Downe acted in four other movies that Lewis directed between 1962 and 1968. She starred in two other nudie-cuties: the silly 1962 Boin-n-g, a movie about an inexperienced producer and director who audition naked women for a movie they want to make, and the first nudie-cutie musical, Lewis’ inane 1963 Goldilocks and the Three Bares, which is set in the same nudist camp as ‘Nature’s Playmates’. Downe also starred in two of Lewis’ dramas. His 1963 melodramatic Scum of the Earth which has a far more serious tone than the nudie-cuties. Her character, the brunette Kim Sherwood is blackmailed and threatened after she does some scandalous modeling to help pay for her college tuition. In Lewis’ 1968 melodrama, Suburban Roulette — Downe, who does not have the starring role, plays the red-headed, slightly older, seen-it-all Margo, in a movie about wife swapping in suburbia. ‘Suburban Roulette’, a lesser- known Lewis movie, was the last film Downe acted in. Interestingly, Downe never acted in any of Lewis’ gore movies, the movie genre he is most well-known for.

Bunny in Goldilocks and the Three Bares (1963)

Bunny in Goldilocks and the Three Bares (1963)

It is impossible to make sense of Downe’s work in the movies, without recognizing the significance of the director Herschell Gordon Lewis. Well known for his exploitation movies of the 1960s and early 1970s, Lewis directed 37 exploitation films in twelve years. Jeffrey Sconce explains that Lewis’ “…oscillation between sexploitation ‘roughies’ and gore-soaked drive in horror in the 1960s is a sleazeography without peer, a body of work that confronts the entire spectrum of sensationalism with a uniformly leaden style.”[16] Known as a showman who mostly wanted to make money by making cheaply made movies, Lewis remains popular with fans and scholars of exploitation cinema. Lewis is credited with inventing the genre of gore as well as making great contributions to the nudie-cutie genre. As Eric Schaefer explains, Lewis movies Blood Feast (1963), 2,000 Maniacs (1964), and Color Me Blood Red (1965) “…include special-effects scenes of torture and dismemberment in graphic color that provide the spectacle for a new class of exploitation films.”[17]

Downe was an indispensable to Lewis’ film career, though she has not been recognized as a key player. She worked with Lewis, as I mentioned, as an actor, in five of his movies, and she also served as his assistant director in six of Lewis’ movies: A Taste of Blood (1967), The Gruesome Twosome (1967), The Girl, the Body, and the Pill (1967), Blast off Girls (1967), The Wizard of Gore (1970), and The Gore Gore Girls (1972). Not only was she an actor and an assistant director, she also did makeup (she has five makeup credits); created the gory special effects (she has four special effect credits) and did costume design (she has one special effect credit) for a variety of Lewis’ films. Downe also wrote six of Lewis’ movies. Besides the ground-breaking screenplays, ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ and ‘She Devils on Wheels’, she is also credited for writing the screenplays for ‘Blood Feast’ (1963), ‘The Gruesome Twosome’ (1967), and Linda and Abilene (1969), though Lewis in 2012 would discredit her for ‘Blood Feast’ and ‘Linda and Abilene’.

Downe and Lewis worked closely together for a decade, and then went their separate ways, never to work together again. In 1972, when Downe and Lewis both quit the movie business, Downe left public life entirely, and Lewis quickly made a new name for himself as an author of instructional books about writing copy for direct mail and later the internet. Late in his life, when his films were being rediscovered by film geeks, Lewis resurfaced to direct Blood Feast 2: All U Can Eat in 2002. When Lewis was 86, in 2012, the book ‘The Godfather of Gore Speaks: Herschell Gordon Lewis Discusses his Films’ was published. In the book, Lewis talks about the memorable moments about each of his films. For whatever reason, in ‘The Godfather of Gore Speaks’, Lewis routinely dismisses Downe’s contributions to his films.

First, he incorrectly explains that Downe’s real name was Louise Povoromo, and that she was valuable beyond her acting because “…she knew everyone in the business in Miami. Which we did not. If we wanted to shoot in the Deauville Hotel, which was absolutely impossible, it would then become possible thoroughly some possibly subterranean connection she had.”[18] Lewis also states that the script for ‘Blood Feast’ was credited to Downe, “…but, in reality the script came together piece by piece as we shot the script.”[19] Finally, Lewis explained that Downe was credited with writing the screenplay for ‘Linda and Abilene’, “…but we gave her credit for a lot of the scripts. The truth is that the scripts for every Tom Dowd film were made up on the fly.” [20] In Lewis’ book, there were only a few mentions of Downe though Lewis and she had an extremely productive decade of making films together. Interestingly, exploitation movie fan sites on the internet, routinely maintain that Downe and Lewis were married. While this is not true, it does suggest that they are closely linked to one another in the public imagination of exploitation movies. It is unclear as to why Lewis, at the end of his life, wished to diminish her contributions, but it certainly helps us to understand why she remains an obscure figure in the 2020s. Lewis died in 2016, and while Downe is still alive, she does not discuss her decade-long movie career, which also contributes to her obscurity.

As I have maintained, Downe contributed to the exploitation movie movement as an actor, assistant director, designer and screenwriter. Lewis claims that Downe did not write ‘Blood Feast’, nor the Tom Dowd movies — which include ‘Nature’s Playmates’, ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bares’, The Alley Tramp (1968), The Ecstasies of Women (1969), and ‘Linda and Abilene’. Lewis, however, did not suggest she was not responsible for scripting ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ or ‘She Devils on Wheels’. The movies that Downe is credited with writing are distinct from the rest of the movies she worked on with Lewis; in part, because the stories are not Lewis’ typical fare of gore and sex. Instead, her scripts focus on the conflicts and pressures young adults face, living in the modern world. In addition, the resist some of the ways women’s bodies were shown on the screen.

Bunny in Goldilocks and the Three Bares (1963)

Bunny in Goldilocks and the Three Bares (1963)

*

The Girl, the Body, and the Pill (1967)

‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ is the more socially conscious than ‘She Devils on Wheels’. Besides writing the screenplay, Downe was also the assistant director for the 1967 movie that advocates for sex education, including education about birth control. The Federal and Drug Administration first approved oral contraceptives in 1960, and by 1967, the year ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ was produced nearly 13 million women in the United States were taking birth control pills. ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ documents some of the anxieties around sex, pregnancy and contraception that young adults were facing in the late sixties.

The movie begins with the young and fashionable Miss Barrington (Marcia Rhae) teaching hygiene classes at an unnamed high school in the Chicago area. She is directed to meet with Mr. Price (Otto Schlesinger), who is the principal. He tells her that she must stop teaching her hygiene lectures, which include information about using birth control pills. Miss Barrington earnestly believes that such education is important and decides to continue her hygiene lectures at her home. The students provide Miss Barrington with permission letters from with their forged parents’ signatures. Meanwhile, one of Miss Barrington’s students, Randy, (Nancy Lee Noble) decides to steal her single mother’s birth control pills and replace them with saccharine tablets. Another one of Miss Barrington’s students, Alice (Kay Ross), has fallen for Roy (James Nelson), a boy in her class. Unfortunately, Alice’s father, Mr. Nichols (Bill Rogers), who has complained about Miss Barrington’s hygiene lectures, forbids her to date Ray or anyone else because at 16, she is too young to date boys (and because he and his wife had sex before marriage, she got pregnant with Alice, and Mr. Nichols was resentful that he had to marry her).

Mr. Nichols goes to Randy’s home so that her mother, Mrs. Hunt (Valedia Hill), can show him Randy’s hygiene lecture notes. The notes suggest that the hygiene lectures have not stopped, and while Mr. Nichols is angry, he is also aroused. Within five minutes of being at Mrs. Hunt’s home, he and Mrs. Hunt begin kissing each other passionately. Later, Mr. Nichols goes to Mr. Price’s office and angrily confronts the him for allowing Miss Barrington to continue teaching sex education. Mr. Price defends Miss Barrington, but it does not take long for him to discover that indeed she has been teaching sex education at her home. Even though she didn’t know the parents’ signatures were forged, Miss Barrington is suspended from her teaching position.

Meanwhile, Mr. Nichols discovers that Alice is seeing Ray, and he explodes and makes Alice breaks up with Ray. Ray loves Alice but starts dating Randy, who is happy to have casual sex with her classmates. Mr. Nichols and Mrs. Hunt are in the throes of a passionate love affair, but unfortunately Mrs. Hunt gets pregnant because she has been taking saccharine pills while Randy has been taking her birth control pills. When she has an abortion at home, Mr. Nichols stops by to say he is truly sorry and then goes home to his wife (Eleanor Vaill) and daughter. A deranged student, Pike (Roy Collodi), breaks into Miss Barrington’s home and rapes her. Her dopey doctor boyfriend (George Brown) rushes over to her house to save her, though it is a little too late because she has already been assaulted.

When someone calls the Nichols’ home, Mrs. Nichols picks up and expresses concern about the subject of the phone call. When Mrs. Nichols asks if the person died, Mr. Nichols falls apart because he thinks Mrs. Hunt has died from her abortion. When Mrs. Nichols gets off of the phone, Mr. Nichols is so distraught that he tells his wife that he will give her a divorce if that is what she wants, but he still loves her. As the call to Mrs. Nichols was about Miss Barrington’s rape, not about Mrs. Hunt’s abortion, Mr. Nichols confesses unwittingly to his affair with Mrs. Hunt. For reasons that are not clear, Mrs. Nichols forgives him. Surviving the crisis, Mr. Nichols becomes a new and better man and allows his daughter to begin dating Ray. He also finally understands Miss Barrington’s reasoning for teaching sex education. After her rape and Mr. Nichols’ raised awareness about the importance of her hygiene classes, Miss Barrington is reinstated at the high school. The principal explains to Mr. Nichols that Miss Barrington’s rape has nothing to do with her lectures; the rapist’s depravity was an exception not the rule. At the end of the movie, Miss Barrington marries her goofy doctor boyfriend, and Ray and Mr. Nichols have a nice chuckle together after the wedding.

Obviously, ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ is far from a light hearted and gentle nudie-cutie, the kind of movie that Downe starred in, just a few years earlier. In some ways, her story subscribes to the blueprint of exploitation movies—namely, by the portrayal of Miss Barrington’s rape and Randy’s casual attitude toward sex. However, Mrs. Hunt’s painful at- home abortion is not typical exploitation fare. In fact, the depiction of an at-home abortion in ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ is cinematically ground breaking, as it was one of the first portrayals of abortion (immediately following the abortion) exhibited on a movie screen in the United States. Most women in American movies who became pregnant accidentally, either birth the child or kill themselves.[21]

The image of Mrs. Hunt, who is left to bleed on her plastic covered sofa after her abortion, is powerful and provocative. By portraying a woman and her blood immediately after she has had an abortion, Downe’s script subverts a cinematic boundary regarding a woman’s body that had been in place since the beginning of commercial movie making.

Interestingly, Lewis does not mention the abortion scene in his recollections of the movie. All he remembers about the movie is that “’The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ performed adequately at the box office, but it didn’t knock them dead the way I had hoped it would,” Lewis writes. While much of what Downe thought about her participation in the exploitation movie movement remains a mystery, thanks to the 1968 Detroit Free Press article, we know for certain the Downe believed in her movie’s message. “This is a good picture for young people,” Downe explains. “It’s such a difficult world,” she says. “Although some people won’t agree, I would rather have them cope with the problem this way, than to have an unwanted pregnancy.” ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’, aims to educate young adults that if they use birth control they need not endure either unhappy marriages nor abortions. The movie’s abortion scene is a critical moment in disruptive cinema, and as such, The Girl, the Body, and the Pill deserves far more cinematic recognition than it has received.

*

She Devils on Wheels (1968)

‘She Devils on Wheels’ is not a socially progressive movie like ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’. It is, in fact, a pretty raunchy story about a women’s motorcycle gang that appeared on movie screens in 1968, a year after ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’. It was shot in the rural town of Medley, which is in Miami-Dade County, not far from where Downe grew up. At the beginning of the movie we see a nicely dressed Karen (Christie Wagner) leaving her house, carrying an overnight bag. She gets in her car and drives away; when she finally arrives at a garage in a warehouse district, she pulls in the garage and the door closes behind her. When the door opens again, Karen is on a motorcycle, wearing short shorts, knee high boots and felt vest sporting a pink cat head and the word ‘Man-Eaters’ on the back. The statuesque Karen takes off on her motorcycle to meet with her friends who are a part of the women motorcycle gang, the Man-Eaters. They spend time in an abandoned house and race their motorcycles at an abandoned airport runway. When the leader of the Man-Eaters, Queen (Betty Connell), asks Karen if she is going to race or watch, Karen seems ambiguous about the winning prize, which is first pick of the guys who hang out with the Man-Eaters. “You treat men like they are slabs of meat, hanging at the butcher shop,” Karen explains. “It’s about as romantic as buying a hunk of bologna.” Queen replies laughing, “That’s me, the original Man-Eater.”

In the next scene, eight Man-Eaters sitting on motorcycles and one apprentice Man-Eater sitting on a scooter are ready to race at an abandoned air strip. The countryside is quintessential Florida in the mid twentieth century—the land is flat and sandy, with scrubby vegetation here and there. Queen, who is not on a bike, is in charge, checking everyone’s bike before the race starts. She wears tight tan pants, a pink turtleneck and matching pink knee high boots, with the requisite Man-Eater vest. She tells the Man-Eaters that she is going to judge who wins the race, but some of the women object because she has to race just like the rest of them so to choose her man. Finally, it is determined that the intern Honeypot (Nancy Lee Noble) who will judge the race because she has to apprentice before she gets to participate in the Man-Eaters’ racing and the subsequent romps with men.

Most of the Man-Eaters in She Devils on Wheels were in all-woman Miami motorcycle gang. While their acting skills are somewhat limited, many of the women on screen could really ride a bike; thus, the racing scene looks fairly legitimate. We are able to see more of old rural Florida as the Man-Eaters race down the abandoned air strip. After the race is finished, Honeypot tells the young women the order of crossing the finish line. They joke about the men they are going to ravish once they reach their clubhouse. After they climb back on their bikes, we see more rural landscape as the young woman ride down deserted roads, with nary a building in sight. When the Man-Eaters finally arrive at their clubhouse, they dismount their bikes and head into the clubhouse where there are young men waiting for them. For the first eighteen minutes and forty-five seconds of She Devils on Wheels, nearly a quarter of the movie’s runtime, not one man is on the screen.

‘She Devils on Wheels’ may be crass, but like ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’, the movie manages to disrupt the male-centric boundary that had been in place since the beginning of commercial movie making–while working with the confines of the exploitation genre. Prior to ‘She Devils on Wheels’ there were only a few commercial sound films produced in the United States that came close to being as female centered: ‘Stage Door’ (1937), ‘The Women’ (1939), and ‘The Trouble with Angels’ (1966).[22] Prior to the production of She Devils on Wheels then, there were three movies out of the roughly 26, 192 sound films (from 1930-1967) produced in the United States, that were as female-centric as ‘She Devils on Wheels’. In other words, out of all the movies produced in the United States from 1930 to 1968, one out of 8,730 of them had predominantly female casts, with female driven stories. Downe’s formula of omitting men on the screen seems simple enough, but when we look at how unusual the omission of men actually is, we can see that Downe was realigning what film viewers saw on the screen.

The Man-Eaters enter their clubhouse, following Queen, who rides inside on her motorcycle. There is a dozen or so men waiting inside for them. Queen inspects them and then tells the crowd that Karen gets first pick. “What will it be, honey?” Queen asks Karen. “A stud? The crowd laughs. “A bronc?” They laugh again. “Or maybe you will really join the club and pick a filly.” The Man-Eaters and the guys laugh uproariously, but Karen chooses Bill, who smiles broadly and tells her he is flattered. Queen gets second choice and grabs “the stud” by his belt and says, “I think I’ll try a little of that old hard Rock.” Everyone laughs and she says, “It’s up to you, Papa.” He replies, “Let’s get it on Mama, I’m ready,” The Man-Eaters continue down the line choosing men, and subsequently they begin frolicking about the clubhouse. It is a fully clothed, lighthearted affair, with lots of shenanigans, wrestling, and laughter.

In a room separate from the rest, Karen asks Bill (David Harris) if he would like to sneak out of the clubhouse and go for a walk, just for a change. Bill balks at the suggestion and convinces Karen to stay in the room with him. When she lies down with him, she asks Bill if he likes her more than the rest of the Man-Eaters. As he starts to take off her shirt, he says without conviction, “Sure I do, Babe. Sure, I do.” The next morning, events take a sinister turn when the Man-Eaters (sans Karen) discuss Karen’s attachment to Bill. Because she has romantic feelings for Bill, one of the Man-Eaters suggests they “work her over a little.” The next evening, Karen meets the rest of the Man-Eaters on the racing strip. Queen, who is dressed in a spectacular silver suit and matching hat, pulls up on her motorcycle with Bill hanging over the back of the seat. Karen screams when she sees him. As he falls to the ground from the motorcycle, Queen tells Karen to cut the dramatics. “We think you are sweet on this gutter bum, and that’s against the rules, lady.”

The young women in ‘She Devils on Wheels’ are not looking to fall in love with men, like most single women in Hollywood movies are trying to do. Rather, the Man-Eaters’ doctrine is to use men for sex, with no emotional attachments. That they punish Karen because she is romantically attached to Bill crudely flips the Hollywood script. Queen tells Karen that if she is not sweet on Bill then she won’t mind dragging his body behind a motorcycle. If she cannot do it because she is romantically attached to him, then she will get dragged down the strip instead. Crying she gets on her bike, and the Man-Eaters tie Bill’s hands to her bike. Karen sobs as she drags Bill down the abandoned runway; his bloodied and mangled face and hands are reminders of the gory effects Lewis is famous for.

After the gooey initiation of Honeypot (the Man-Eaters taste her blood, kiss her, and spread oily substances on her), the guys the Man-Eaters hang out with surround her, and Honeypot (who in her bra and underwear looks like Carrie after the blood is poured over her) says to them, “All right fellas this is what I’ve been waiting for. Come on and have a taste of Honey.” Thankfully, we don’t see what comes next, as She Devils on Wheels cuts to the next scene in which the Man-Eaters harass the locals and the police. Then the women encounter some young men who are driving their cars on the Man-Eater’s racing strip. The young women are furious with this encroachment, and they get into a brawl with the men; using tire irons, knives, and chains, the young women overpower the men, leaving them bloodied and on the ground. The strength and cunning of the Man-Eaters overwhelm the young men, who mostly look like models.

Interestingly, the scene following the hyper-masculine affray, is a more traditional view of women, for Karen getting out of the shower. She has a towel wrapped around her head and another wrapped around her body. She looks in the mirror and winces at the bruises on her face, when the phone rings. We discover that it is Ted and Karen agrees to meet him for a cup of coffee. Ted (Rodney Bedell) turns out to be a handsome young man in a cardigan that Karen used to date. He tells Karen that his brother’s gang is out to get the Man-Eaters—to snuff them out. Karen does not seem surprised to hear the news, and she tells Ted that the Man-Eaters know how to handle themselves.

When Ted shows up unexpectedly at the clubhouse, he tells Karen that Joe-boy and his gang are going to tear their place apart. Ted tells Karen he will take her away by force- if he has to- because he is afraid for her welfare, but Karen does not believe there will be trouble and does not leave the clubhouse with Ted. Meanwhile the Man-Eaters kiss and hug the guys that have gathered at the clubhouse. Everyone except Honeypot and the man she is kissing (they are in a private room and their shirts are off) is fully clothed. The women even wear their felt Man-Eaters vests as they playfully make out with the young men.

Honeypot puts her shirt back on, and she wanders outside, only to get abducted by Joe-Boy (John Weymer) and his gang. We do not see what they do to Honeypot, only that they return her the next day, unconscious and bloodied. Queen gathers the Man-Eaters so that they can take revenge on Joe-Boy and his gang. The women look for them at a local bar, but to no avail, so Queen devises a plan. In the next scene, we see some of the Man-Eaters wrapping thick wire around two telephone poles that bookend a road, and then we see the same women arriving at Joe-Boy’s hangout. The Man-Eaters provoke Joe-Boy and then take off on their motorcycles. Livid, he takes off after them. Regrettably, Joe-Boy is decapitated when his head hits the wire wrapped between the two telephone poles. His head goes flying. The Man-Eaters laugh and cheer as Joe-Boy’s head lands on the ground. Later, Ted asks Karen to leave the Man-Eaters and come with him so she can lead a more virtuous life, but she walks back to the Man-Eaters and gets on her motorcycle. Flipping the script once more, Karen chooses the Man-Eaters over the cute boy who drives a Corvette. When the Man-Eaters head back to the decapitation site to look for Queen’s garrote, a cop shows up. He holds the garrote in his hand; it is the evidence he needs to arrest the Man-Eaters. Quite out of character, they follow him without protest—presumably to his police car and then to a jail cell.

*

Conclusion

Lewis explained that ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ and ‘She Devils on Wheels’ were a mixture of documentaries and dirty movies. While he was likely more interested in the dirty movie part of the equation, both movies do document the zeitgeist of the late 1960s, in ways that are historically significant and worthy of our attention. To begin, both movies document daily life in the late 1960s. Because they were low budget productions, there were no elaborate sets constructed. We are privy, instead to authentic suburban neighborhoods, the interiors of middle class homes and a high school with its traditional 1960s classrooms, complete with a 16mm film projector. ‘She Devils on Wheels’ documents the riding talents of a real women’s motorcycle gang in the late sixties, commercial buildings in the Miami-Dade area in 1968, and Miami’s rural landscape before its over-development began. ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ and ‘She Devils on Wheels’ also document the anxieties that young people routinely faced both in the 1960s (and today): the perils of romantic commitment, the potential bodily and emotional risks of sexuality, the joy and complexities of trying to fit in with peers, and the potential for public exile if group assimilation is not done properly.

Both movies, however, do more than document the artifacts and anxieties of daily life in the 1960s. They both significantly disrupt the way women and their bodies had typically been presented on the movie screen in the United States. The abortion scene in ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ is a monumental moment in American twentieth century cinema because it is the first abortion scene depicted on a movie screen in the United States. When we see Mrs. Hunt lying on her plastic covered sofa immediately following her abortion, her body is neither sexualized nor domesticated; rather, Mrs. Hunt is portrayed as a woman in pain; one who bleeds right after her at-home illegal abortion. Produced prior to legal abortions in the United States, ‘The Girl, the Body, and the Pill’ still remains relevant in 2024, as conservative courts work to dismantle women’s right to choose. ‘She Devils on Wheels’ also unsettles traditional boundaries of cinema by the simple exclusion of men. We see only fully clothed, strong, motorcycle-riding women for the first quarter of the movie. Without a man in sight. Prior to ‘She Devils on Wheels’ there were only a few commercial sound films produced in the United States that came close to being as female-centric.

Louise Downe’s contribution to American cinema is significant, and her work deserves our attention. She was a screenwriter and moviemaker ahead of her times. Few women in the 1960s and early seventies cinema had as much influence as Downe did, and she was a pioneer in subverting the way women and their bodies were typically seen on the screen. Hopefully, this essay will provoke others to research and write about Downe and her work, so we can have a fuller understanding of her many contributions to American moviemaking in the 1960s and 1970s. In addition, it is likely that other women who worked in the exploitation movement have also been overlooked. Their contributions also deserve to be understood, so we have a deeper understanding of American twentieth century movie history.

*

Notes:

[1] “The Teen Counselor Who Wrote Those Shocking Movie Scripts,” Detroit Free Press, January 5, 1968, p. 5.[2] Ibid.

[3] I use the name Louise Downe because this is the name she went by in the 1968 Detroit Free Press article.

[4] “Lives at Beach After Decade,” The Miami Herald Sun, April 13, 1941, p. 21.

[5] “Shenandoah Speech Event Finalists Listed,” The Miami News, May 18, 1951, p. 27.

[6] “New Appointments Listed by Red Cross Chapter,” The Miami News, August 31, 1952, p. 12.

[7] “Red Cross Unit Picks Students for Convention,” The Miami News, June 9, 1953, p.20.

[8] “Happy Birthday, Bonnie,” The Miami News, August 14, 1953, p. 17.

[9] “Formal Rush Ends for UM Sororities,” The Miami News, October 14, 1955, p. 20.

[10] “U-M Coed Wins Title,” The Miami News, July 10, 1956, p. 19.

[11] “Title Lovelies Tell Why They Try,” June 8, 1956, p. 1.

[12] “Dateline Miami, Herb Rau,” Miami Daily News, June 24, 1957, p. 18.

[13] “Summer Begins in a Social Way,” The Miami News, May 28, 1958, p. 15.

[14] “Downe-Thorne,” The Miami Herald, May 17, 1959, p.113.

[15] In Matter of Excelsior Pictures Corp. v. Regents of Univ. of State of NY (3 N.Y.2d 237, 240)

[16] Jeffrey Sconce, Sleaze Artists: Cinema at the Margins of Taste, Style, and Politics, ed. Jeffrey Sconce (Durham and London: Duke University Press), 2007, p. 5.

[17] Eric Schaefer, “Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!”: A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959, (Durham and London: Duke University Press), 1999, p. 289.

[18] Herschell Gordon Lewis, The Godfather of Gore Speaks: Herschell Gordon Lewis Discusses His Films, (Duncan Oklahoma: BearManor Media), 2012, p. 37.

[19] Ibid., p. 49.

[20] Ibid., p. 116.

[21] While portrayals of abortion in the movies and on TV increased after abortion was legalized in the United States, prior to 1973, there were very few portrayals of abortion on the screen—primarily because the Production Code forbade movies from depicting abortions or discussing the practice of abortion. Nevertheless, the low budget 1962 The Shame of Patty Smith is about a young woman who was raped and is pregnant, and must seek a back-alley abortion because she has nowhere else to turn, and in the highbrow 1964 The Pumpkin Eater, the main character (Ann Bancroft) has an abortion but we do not see it on screen. The popular British 1966 movie, Alfie, helped to effectively change the ban on portraying abortions on screen, as Jack Valenti, the MPAA chairman, not only gave Alfie an exemption but also at the same time circulated a memo calling for a major overhaul to the Hays Code. The motion picture rating system that replaced the Hays Code went into effect in 1968. The Girl, the Body, and the Pill was exhibited in theaters after the memo went out and before the motion picture rating system went into effect.

[22] While there are two men in the frame in the first scene of Stage Door, male characters with speaking parts do not appear until twenty minutes into the film. Adolphe Menjou who plays a casting couch producer is critical to the narrative of Stage Door. There are no men characters in The Women; though there is a photo of a man in a magazine that Peggy (Joan Fontaine) looks at. In The Trouble with Angels there are a few men (pedestrians, a train conductor, a crew member, and several passengers) who appear in the first minutes of the movie, and there are several secondary male characters in the second half of the movie.

*

Bunny in Goldilocks and the Three Bares (1963)

Bunny in Goldilocks and the Three Bares (1963)

*

This is a real treat – and the icing on the cake after the epic recent series. Indispensable!

Thank you, Nicole!

Very interesting and fresh take on the HGL’s career. Good to see it re-evaluated in this way.

Always challenging history – and well-written too.

Thank you, Tom.

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work

Thank you so much, Jeff.

Great article! Question to those “in the know”: is Downe still alive? If so, has anyone attempted to interview her in regards to her film career??? Also, the issue as to why H.G. Lewis didn’t speak much about Downe after “The Gore Gore Girls” was supposedly she had something to do with his brief bankruptcy in the mid 1970s.

Hi Chris–she is still alive, but isn’t interested in speaking about her past, unfortunately. I believe her work was important, and hopefully there will come a time when she is willing to speak about it.

Interesting. I’m surprised she doesn’t want to talk about her film past; is she aware of the cult fandom of Herschell Gordon Lewis for her to at least offer a few tidbits. I’d love to hear her side of the story in regards to her split from Lewis and the bankruptcy situation; it seemed that once Lewis went thru his financial and legal situations, Downe made a hasty retreat.

The two pictures of Bunny from Goldilocks and the Three Bares looks like actress Sherilyn Fenn

Also to add: Sepy Dobronyi is the guy who has a “Coke” problem and gets blown by Linda Lovelace in “Deep Throat”! Dobronyi ended up in that film because director Gerard Damiano shot that scene in Sepy’s basement den. Dobronyi was also briefly interviewed in the documentary “Inside Deep Throat”.

thanks so much, always been “DOWN” with her. ha ha oh my. Tangentially if you are interested in female genre screenwriters Pat Fielder is pretty interesting. Not Rialto material per se but a peer of sorts to Downe.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pat_Fielder

Thanks for the tip about Pat Fielder.

Janna welcome please check out “the vampire”. it is seething with repressed sexuality, oedipal lust. I mean cringe isn’t that a bit too on the nose omigod I can’t look at this level.

I had always thought they were married at one point as well. Where did that rumor start?

GREAT guest article – I wish Janna all the best with her script as this would be amazing to see on the big screen, and would certainly attract much attention to this topic.

Thanks Janna!

Thank you so much, Lee.

I hope Louise reads this and sees how important her contribution has been – and grants an interview to Janna and The Rialto Report.

Hi Carlton, I hope so too!

Every one should read the synopsis for she-devils on wheels! The plot is insane! Theses have been fantastic thank you Rialto!

Great essay. It’s sad that HG Lewis diminished her contributions once his films gained a cult following, especially considering that she was involved in so many of his productions. I think she did the hard work and vanished from the public eye after not being recognized for it. I read a quote from HG Lewis claiming that there was no actual script for Blood Feast, which is ridiculous considering that any feature, particularly one with a tight budget, has a detailed screenplay, if only so actors get their lines right, thereby conserving film and maintaining continuity and for logistical purposes such as locations and actor schedules. Writing even not-so-great writing (and I’ve done some) is arduous work. This is another example of a woman getting shut out of the boy’s club. I hope she consents to an interview. She deserves recognition. FYI—she and Lewis were never married. Rialto rocks.

Insanity – in the best way!

I prize my copy of ‘Herschell Gordon Lewis And His World Of Exploitation Films’ , signed by HGL.

HG’s skills seemed to deteriorate the more films he made, but we can’t all be Orson Welles, right?

Louise is one of the keys to the whole era – and an interview with her would be so important. I hope she consents because this history – and her memories – are vital to preserve!

Louise is one of the keys to the whole era – and an interview with her would be so important. I hope she consents because this history – and her memories – are vital to preserve!

It would be so interesting.

She is gorgeous! She reminds me of a young Sherilyn Fenn from the film Two Moon Junction!

Hello all,

I am Bunny/Alma’s 2nd cousin. Sadly, I am reporting that she passed away earlier this summer-June 24, 2025. I only knew here for 4 years, but am glad I got to know her.