Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Previously on Chasing Butterflies – Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida:

Dolores Carlos was from a fiercely Cuban family, even though she was born in Tampa, Florida in October 1930, and never visited her country of origin. Her Cuban heritage and good looks, not to mention her patriotism, came from her father, Gus, and grandfather, Carlos, who had run the family’s cigar making business.

Growing up was complex for Dolores: she was close to her family, but she dreamed of breaking free and having a glamorous life as an actress, seduced by the silver screen and the movies of 1940s that she cut school to watch. At 17, she broke away, but found herself swapping her strict family home for married life – and being a stay-at-home mother after she gave birth to her daughter, Marcy.

The marriage ended in divorce, and Dolores needed to support herself – which she did by modeling: she modeled for Webb’s department store, newspapers, pin-up photographers and local businesses. Her career quickly took off, aided by winning beauty contests and making personal appearances at fairs, carnivals, and balls. Within no time, her pictures were appearing all over the land – even in other countries. She became close friends with a Miami model, Louise Downe, also known as Bunny, and they often worked together.

Most of all though, Dolores wanted to work in films: she introduced herself to every producer she could find and turned up at every audition, but when she turned 30 without any offers, she figured that her dream was probably not going to happen.

Then in 1958, Doris Wishman contacted her. Doris had had a career in film distribution, but following the death of her husband, had decided to make a nudist camp film, ‘Hideout in the Sun’, and wanted Dolores for the lead role. Dolores accepted with a degree of nervousness given the subject matter – and her fears were realized when Doris and Dolores were both arrested filming a nude scene on the beach in Miami, and Dolores was found guilty of indecent exposure. It was a scandal that was splashed across the newspapers and shocked her family.

For Dolores however, the arrest, and the subsequent success of the film, proved to be a watershed moment: she finally felt independent and decided to double down and move to Miami where she could pursue the new film and modeling opportunities that were now coming her way. She appeared in several more nudist camp films, countless newspaper photo spreads, and became a local celebrity, appearing on stage to introduce visiting Hollywood stars, like Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis when they brought their shows to town. Her life was made even happier when she was joined by her teenage daughter Marcy, who moved to Florida to live with her.

Dolores was often accompanied on her film and modeling jobs by her friend, Bunny Downe, and together they decided to produce their own nudist movie, and so they arranged meetings with various impresarios in Miami. One of these was with K. Gordon Murray, a legendary carny entrepreneur, who was a hugely successful importer of Mexican children’s films which he would skillfully dub for the American market.

But Dolores had another outlet for her talents: on January 1, 1959, Fidel Castro’s communist rebels had seized control of Havana, Cuba’s capital. Many Cubans, fearing the consequences of the new revolutionary government, fled to Miami looking for work and a new life. Among the influx were many who’d worked in Cuba’s film and television industry. Dolores’ passion for helping Cubans and her newly acquired network of film contacts was ideally suited to helping these immigrants find work in the new sex film industry in Florida.

Over the last twenty years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to many of these people. Their overlapping personal histories reveal an untold chapter of adult film history and the hidden role that Cubans played in shaping it.

These are some of their stories. This episode is Part 1: Manuel Conde’s story.

You can listen to the Prologue: Dolores Carlos’ story here.

With thanks to John Minson, Tom Flynn, Ronald Ziegler, Leroy Griffith, Veronica Acosta, Mikey Bichette, Bunny Downe, Mitch Poulos, Sheldon Schermer, Ray Aranha, Manny Samaniego, Barry Bennett, Randy Grinter, Herb Jeffries, Tempest Storm, Chester Phebus, Michael Bowen, Norman Senfeld, Richard Falcone, Lynne O’Neill, Something Weird Video, and many anonymous families and friends who have offered recollections, large and small, over the years.

This podcast is 40 minutes long.

*

1. Manuel Conde – Cuban Beginnings

Manuel Conde was an improbable playboy: at 5’6” and bald as a polished billiard ball, he wasn’t often mistaken for Tony Curtis.

What made Manuel a ladies’ man was a combination of circumstantial factors: for a start, he lived in New York in the 1940s and 50s, where he ran a successful – and glamorous – photographic business, specializing in portraits of wealthy dowagers and Cuban movie stars. You could always spot his pictures: each one was embossed in the corner with his impossibly elegant and unique imprimatur, ‘Conde of New York.’ He got his start in the business after befriending another photographer, a Jewish man Maurice Seymour, who became a mentor to him. Manuel’s business took off, and before long, his photos were ubiquitous.

‘Conde of New York’ photographic portrait

‘Conde of New York’ photographic portrait

Then there was Manuel’s jet-setting lifestyle, splitting his time between Cuba and the Big Apple – in an era when both locations were the playgrounds of the rich and famous.

And finally, there was his enigmatic and mysterious background. Manuel had actually been born José Conde Samaniego in 1917 in Galicia, a fiercely independent kingdom in the north of Spain. For centuries, Galicia had pressed for self-government and for the recognition of its own unique culture, and in 1936, it finally won the right to self-determination by establishing a Statute of Autonomy. The people had got what they had wanted for generations – but this new beginning was frustrated by General Franco. His fascist coup d’état in the same year kick-started a long dictatorship throughout Spain, and so Manuel, barely twenty at the time, fled with his family to Cuba.

But by the mid 1950s, Manuel was bored of the photography business. He loved working with cameras but had grown tired of the high-maintenance prima donnas who posed for his studio portraits. He wanted to start a new career – and he wanted to make films. New York was a closed shop due to the strict unions, so he turned to the nascent film industry in Cuba where he found work as a cameraman on a variety of projects.

In 1956, he teamed up with an aspiring director, Mario Barral, and they made Cuban Confidential (aka ‘Backs Turned’). It was a drab, black and white, pseudo neo-realist drama notable only for the depiction of the pre-Castro Havana streets (“People are real…” – the disclaimer read at the beginning – “any resemblance is a happy or bitter reality.”) Manuel took a producing credit in return for taking the film back to New York with him and seeking U.S. distribution, but it was slog and he would struggle to make any progress in selling the movie in the years ahead.

Nevertheless, encouraged by the experience, Manuel established a small film studio in Havana and shot newsreels of the Cuban political situation for Movietone, the New York newsreel company. He also made an upbeat musical comedy ‘Around Cuba in 80 Minutes’ (1957), featuring entertainers who appeared at show spots on the island, such as the Tropicana in Havana. The movie premiered in 1958 in Cuba, and would later achieve a second life in the U.S. as a nostalgic view of Cuba for homesick compatriots.

Then two major events happened that turned Manuel’s life upside down: first he met Maria Maury, a woman almost twenty years his junior, who became his wife. And then, in 1959, Castro overthrew the Batista government and enforced Communist rule over Cuba. Manuel, having already fled one dictatorship in Spain a few years earlier, wasn’t in the mood to stick around and try life under the new boss. The only things keeping him in Cuba were family, which he could take with him, and his new studio film business which, under the newly-enforced trade embargos, could not be transferred to the U.S. So, to get around the restrictions and to have something to bring as a calling card, Manuel decided to make one last movie – an exciting, commercially attractive feature that he would take with him as he left Cuba behind, and that could he could sell in the U.S.

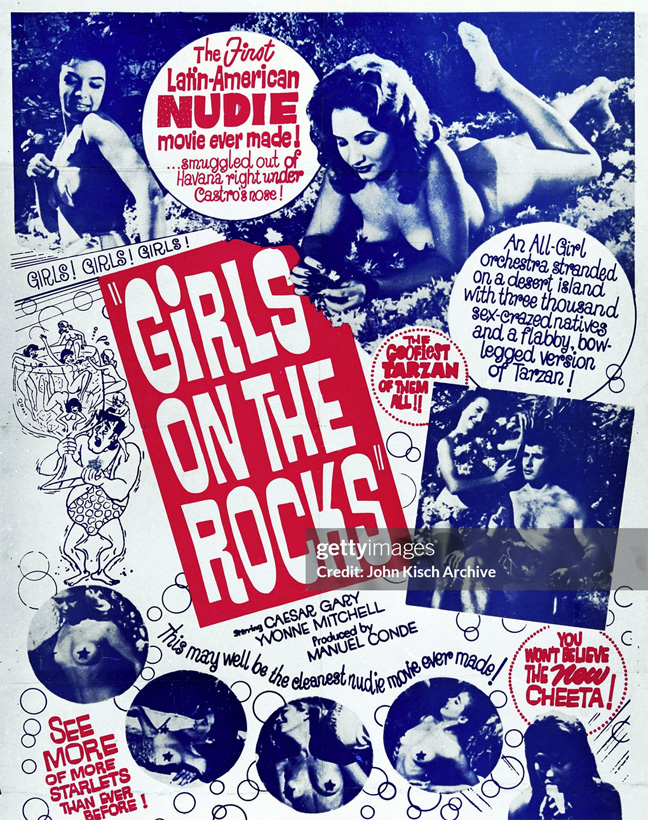

In early 1961, Conde shot a sexploitation film, Girls on the Rocks (originally titled ‘Drums of Cupid’), in a week-long shoot on the outskirts of Havana. It could have been a risky venture given the repressive nature of the new regime, but with his usual combination of charm and obstinacy, he made the film, even getting support and help from some of the communist revolutionaries.

But making the film was only half of the problem: the more dangerous part was getting it out of the country. In late 1961, Manuel arrived at the Havana airport to leave the island for good, with the film reels for ‘Girls on the Rocks’ as well as his comedy ‘Around Cuba in Eighty Minutes’ ready to smuggle both into the U.S.

Conde’s wife, Maria, later explained: “Manuel was flying in and out of Cuba all the time with the newsreels he shot. He had a permit to go to New York to develop color film because there were no color labs in Cuba at the time. So one day he gathered up the family and everything we could carry, and said it was time to leave.”

Not so fast, said the customs officers when they saw the film reels in Manuel’s luggage. Manuel explained that it was just newsreel footage of Castro, but the officials didn’t buy it. They insisted that he needed to leave the footage behind. Manuel called their bluff: he told them to phone Castro’s personal office and experience the dictator’s reaction when he found out that they were trying to restrict news of Castro’s achievements from reaching an international audience. The customs officers balked at the idea, reconsidered, and let Manuel leave with all his film reels. Manuel had won the battle against the dictator he despised, and when ‘Girls on the Rocks’ was eventually released in the U.S., the ads gleefully proclaimed, “Smuggled Out of Havana Right Under Castro’s Nose!”

As for the film itself, in truth, Manuel had missed the boat: the nudie cutie that he’d made wasn’t nudie or cutie enough by American standards of the early 1960s, just showing shapely girls in skimpy bikinis. The nudist films in America had already become more daring. The ads admitted as much: “The Cleanest Dirty Movie Ever Made!” they boasted.

*

2. Manuel Conde moves to Miami

Manuel Conde first met Dolores Carlos in late 1961, just after he’d arrived in Miami, accompanied by his wife Maria and son, Manuel Jr., who’d been born just weeks before they left Cuba.

Dolores quickly became friends with Manuel and his family. It was a symbiotic relationship: Dolores showed them around Miami, taking them to Cuban restaurants in Little Havana and burlesque shows in Miami Beach, and introduced them to other Cubans looking for work in the local film business. Manuel, six years older than Dolores, was like an older brother to her, and was more worldly, advising her and encouraging her career aspirations.

Dolores Carlos, photographed by Bunny Yeager

Dolores Carlos, photographed by Bunny Yeager

Like many of his exiled compatriots who’d worked in television or movies, Manuel considered himself a serious filmmaker. He was intent on finding work shooting documentaries or industrials and showcasing his abilities as a cinematographer, but without a readily-accessible filmography to show off, it was a tough sell to the small pool of Florida producers.

Dolores saw Manuel’s sexploitation film ‘Girls on the Rocks’ and told him about the nudist film craze in Florida. She suggested that perhaps, after documentaries, sex films were the next most authentic form of movie-making. She argued that Manuel should make another movie, an American film this time, that would act as a more up-to-date calling card, as well as a way of making some money – and that Dolores could help him put it together and could star in it as well. It was a tongue-in-cheek suggestion and Manuel was skeptical, but he relented when no other news or documentary work materialized.

The resulting nineteen-minute nudie short, Playgirl Models, shot in December 1961, was a strange hybrid. Two disparate motivational forces were at play: on the one hand, the film was supposedly titillating, featuring five nude (or semi-clad) Florida models (including Dolores and Bunny Downe, of course) shown working on cheesecake photo shoots. But rather than being intent on filming arousing footage, Manuel was more interested in demonstrating the role of the cinematographer to the viewer, showing different types of lighting equipment and explaining how various black & white effects are achieved. The film’s tagline was as accurate as it was unsexy: “A Factual Study of Glamour Lighting and Photography”

Despite Conde’s technical pretensions, ‘Playgirl Models’ was released into grindhouses in April 1962 – specifically the 79th St Art Theater, as the supporting feature for Eve or the Apple, the Dolores feature that she’d made with K. Gordon Murray. Friends recalled her pride in having two films playing in the same theaters, and she made regular appearances in the lobbies to promote the ‘Eve’/’Playgirl Models’ double bill at playdates all over Florida.

*

3. Leroy Griffith

In the wake of ‘Playgirl Models’, Manuel set up a production company, M.S. Conde Productions, with offices at 236 W Flagler St in Miami. One of the people that Dolores had been keen to arrange an introduction with was Leroy Griffith. Griffith was a relative newcomer to Miami, who’d been living and working there for less than a year, but he’d already become a theater mogul in the city.

Griffith was an energetic, entrepreneurial force of nature. Barely over five feet tall but, as film producer Dave Friedman recalled, “most everyone in the business may call (Leroy) ‘midget’ but he had the balls of a burglar.” In a recent interview, Griffith recalled the two pillars on which he built his business empire: “Firstly, I found theaters that were going bust. Regular, legit family theaters that were about to go under. This was because, in the 1960s, everyone was moving out of town into the suburbs… so they left behind a lot of theaters in trouble. I bought them and turned them all into burlesque places.”

“And secondly, I saw the value of concessions: popcorn, candy, drinks, t-shirts, anything you could sell in the lobby. I learned this from the very first job I had when I was a kid when I worked concessions at the Grand Burlesque Theater in St. Louis. I sold candy and trinkets to audiences before and during the intermission. At the end of the night, I noticed something strange: I’d earned more than anyone else. More than the dancers, comics, and comedians!

“I realized then that concert venues were not in the business of putting on shows. Not really: they were in the business of selling alcohol. Just like theaters were really not in the business of exhibiting films: they were in the business of selling refreshments. When you realized the value of concessions, you could really start making money.”

In 1961, Griffith visited Miami Beach and noticed the Paris Theater was for sale. He leased it, then bought it, staging burlesque shows, including many with his favorite dancer, Tempest Storm: “She was a firecracker with a dynamite stage act. We made a big profit with her every time.” Griffith’s success was controversial, and he fought off multiple legal challenges from city authorities who tried to shut the sex trade down, before deciding that South Florida would be the base for his theater business empire. Over the next years, he continued to open new venues throughout South Florida, from Broward County, north of Miami, right down to Key West in the south.

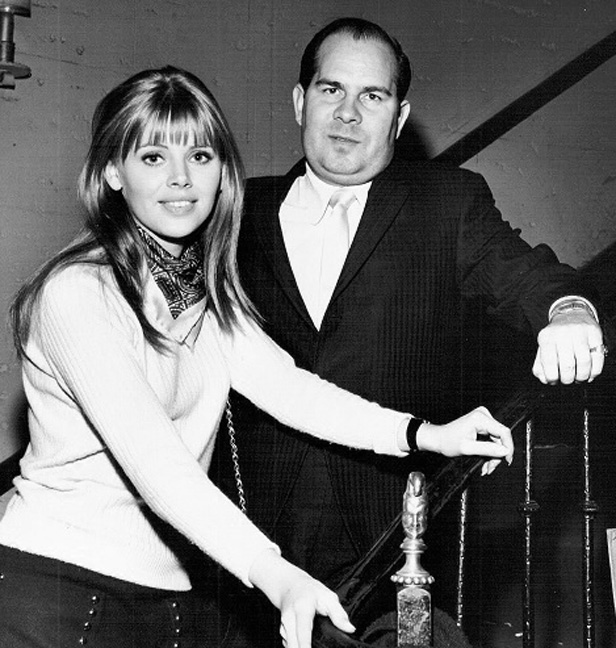

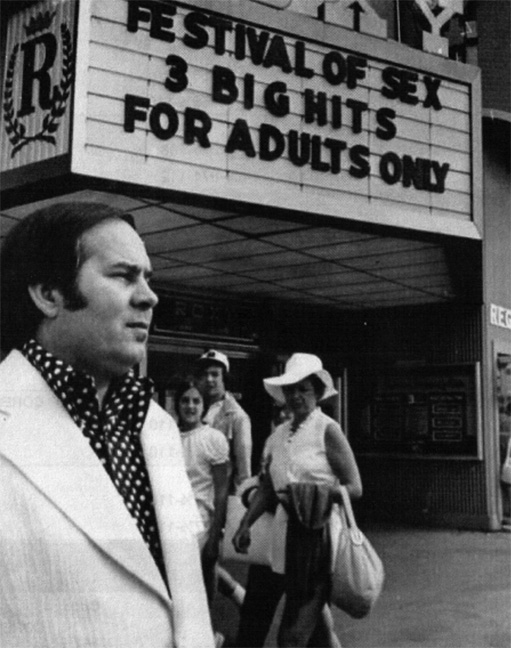

Leroy Griffith, with Britt Ekland

Leroy Griffith, with Britt Ekland

As his portfolio of theaters grew so did his overheads – and he was hit by the expensive staging cost of the burlesque shows. Even worse was the fact that he was getting busted all the time: “Every week they came up with a new reason,” Griffith grumbled. “They said I didn’t have the right license, or the right permits, or I hadn’t paid my taxes, or the shows were too permissive… Once I paid thousands for a license for a burlesque show, and then they told me that they’d decided burlesque was prohibited: it was constant harassment.”

So Griffith hit upon a new, more profitable business model: as he explained, “Burlesque started dying in the 1960s, so I started to switch the theaters into adult movie houses. They were cheaper to run, and the audiences couldn’t get enough of the new sex films. And then, you know, pretty soon after that… I decided to make my own movies.”

Griffith already knew of Manuel and Dolores because he exhibited ‘Eve or the Apple’ and ‘Playgirl Models’ in his theaters across the state, so he was happy to take a meeting with them. Griffith had just produced his first effort, a nudist camp film called Bell, Bare and Beautiful (1963), directed in four days by future gore specialist, Herschell Gordon Lewis. It starred burlesque queen Virginia Bell, a frequent headliner at Griffith’s theaters. It was a crude and inept cash-in on an earlier Doris Wishman nudism-meets-burlesque vehicle, Blaze Starr Goes Nudist (1962), but it played well in Griffith’s theaters and so he was ready to make more along the same lines.

When I spoke to him, Griffith said he was skeptical when he first met Manuel and Dolores: “A nudist broad and a Cuban without a history walk into my office pitching a sex movie? Sounds like a bad joke, right?! Damn right, I didn’t trust them! But we got to talking, and they weren’t asking for much, so we put something together.”

The deal they put together consisted of a couple of episodic short films – both to be directed by Manuel and both to feature Dolores. Griffith threw in a couple of extra sweeteners: he would make Virginia Bell available to co-star, and he also offered them the use of his Miami Beach burlesque theater as a filming location, with other interiors to be shot at Flamingo Studios just down the road.

Manuel turned over the two short films but their running time only added up to 57 minutes – barely adequate for a feature release. Dolores came to the rescue with another recent Cuban immigrant friend that she’d met at (where else?) the Freedom Tower: this one was an aspiring filmmaker called Frank Malagon.

Malagon was a colorful Cuban character, a chameleon with various identities: he was a ceaseless grifter, a benevolent con-man, and a snake oil salesman man who could sell you anything. His only problem was that couldn’t stay focused on any one venture for long: he juggled a dozen hats, but every time he caught one, another was flying off his head. Malagon had started out in public relations in pre-Castro Cuba, parlaying his large network of contacts into handling the publicity for Carol Reed’s Our Man in Havana (1959) starring Alec Guinness, which had been shot in the capital. Avowedly anti-communist, Malagon fled Cuba after the revolution and settled in South Carolina, where he established himself as an outspoken critic of Castro, and the architect behind the effort to set up a symbolic alternative government, La Nacion en el Exilio (‘the Cuban Nation in Exile’). He quickly developed a high profile making several appearances on U.S. television – including the Mike Wallace Show in 1960 – to talk about what he described as the Cuban outrage. His stated plan was to connect exiled Cubans and carry out the overthrow of the Castro government.

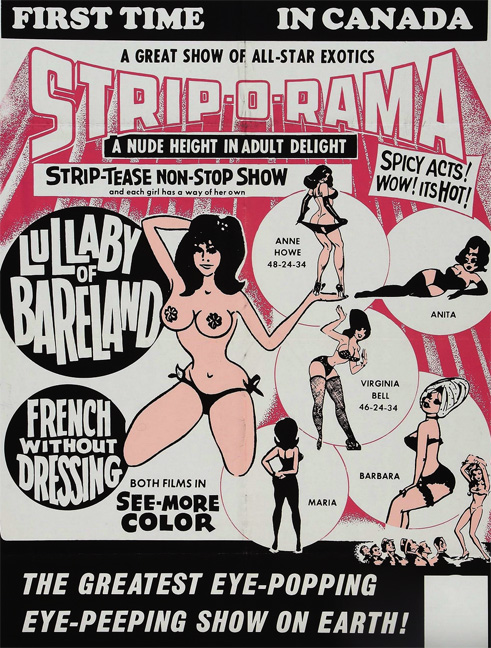

Malagon even set up a film studio to make films as a way of funding his anti-Castro activities, before moving to North Miami in 1963, where he leased the former Channel 10 studio at 21st St and Biscayne Blvd, with a local builder, Dick Flink. At that point, Malagon’s passionate political intentions were somehow sidetracked in favor of low budget sex filmmaking. Malagon and Flick announced a slate of sex and horror films. Dolores encouraged Malagon to shoot a short, ‘The Super Dreams’, as their first film – and it was ‘The Super Dreams’ that Leroy Griffith added to Manuel’s other two short to create a full-length feature. It was called Lullaby of Bareland (1964), and billed as ‘3 Units of Fun!’

Malagon went on to make a couple more films using crews largely composed of Cuban talent provided by Dolores. And that was the extent of Malagon’s film career. A postscript about his colorful life however is worth adding: after the movies, Malagon set up a show-biz talent agency called ‘Shooting Stars’. Then he sold his film equipment so that he could build an anti-poverty city in South Dade County that he wanted to call ‘Youth City’. When he failed to obtain adequate funding, he moved onto a new career in hypnosis and became a mind-control doctor, eventually forming his own church in 1977 – called the Chapel of the Transformer (COTT) – which supposedly helped people find their perfect mate. In the 1980s, he switched gears again, and ran the Miss Miami Beauty pageant, before changing lanes once more to run the National AIDS Awareness Foundation. By the mid 1990s, he was working quietly as a realtor in Palm Beach. Malagon died, presumably exhausted by all his creative endeavors, aged 72, in 1999.

*

4. Home Life

Despite the upheaval of previous years, Manuel settled well in Florida. His son Manuel Jr., born in Havana just before their departure, had been joined by a daughter born in 1963. Dolores’ daughter, Marcy, would often babysit for them. The family lived in the affluent Miami neighborhood of Coral Cables, and Manuel Jr. remembers they lived in the best house in the area, despite the fact it had barely any furniture: “Our life always seemed to be like that! I could never work out why we had the most beautiful homes… without anything in them. But he was a good father, even if he was strict: if he liked you, you were fine. if not, then you were the dog’s dick.”

Not that life had become uneventful: Manuel loved boats and invested in a motorboat with fellow Cuban friends which they used to make illicit nighttime trips back to Cuba. The principal purpose of the sorties was to rescue family and friends who were still stranded in the country – as well as bring back contraband. It was a venture that was fraught with risk – both in terms of making the crossing, and being apprehended by U.S. coastguard, or worse, the Cuban authorities. They souped up the craft so that it could outrun anyone pursuing them – but it didn’t always work. On one occasion, on the eve of another secret trip to Cuba, Manuel slept through his nighttime alarm and missed the boat’s scheduled departure time so they left without him. That night the boat disappeared, his three friends never making it back – their fate still unknown. A reminder of the potential dangers of trying to gain access to the island.

On the work front, Manuel still wanted to find work in the world of newsreel and industrials as he viewed it to be a steadier and more reliable source of income than features. He was reasonably successful – cameramen with their own equipment were always in demand – and he found work for several auto companies, such as American Motors. One notable short in particular, Shelby Goes Racing (1965), saw Manuel shooting Carroll Shelby, one of the finest sports car drivers of his generation.

*

5. Nudie Cuties

In his spare time, Manuel could often be found at the Gayety Theater on Miami Beach, courtesy of new friend and sometime producer of his films, Leroy Griffith. Griffith admits his theaters were always at the heart of it all: “One time Sammy Davis Jr., Frank Sinatra, and Belle Barth came into the Gayety. We had a Chinese dinner together, and then started watching the coming attractions for an X-rated film that was going to be running. For fun, we shut the sound off and the three of them – Frank, Sammy, and Belle – improvised the sexual sounds to go along with the scenes. They were all moaning and groaning and making funny noises. It was hysterical.” Dolores even managed to convince Griffith to convert one of his sex film theaters, the Dixie at 222 NE First Ave, into a Spanish language revue and film venue.

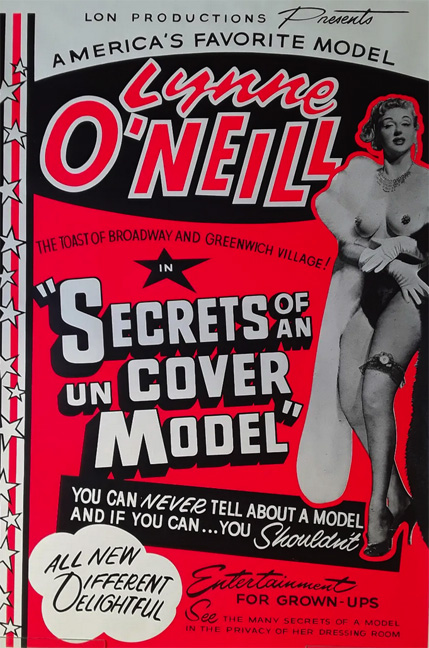

In 1963, Manuel saw burlesque star Lynne O’Neill at the Gayety Theater – and he was smitten. Not smitten in the leave-your-wife kinda way, but rather smitten in the inspired-to-make-a-film way.

Lynne O’Neill was a pneumatically-endowed blonde powerhouse, known as ‘The Original Garter Girl’ because her signature routine consisted of bestowing garters to audience members at the end of her shows – a gimmick suggested by, of all people, her mother, who accompanied her on the road. By the time Manuel first saw her, Lynne was already a veteran performer in her mid 40s, but she was still a big draw. Everyone had heard of her at that time because of a highly-publicized arrest in March 1960, when Lynne had been accused of distributing nude photographs of herself through the mail. She was convicted and served four days of a ten-day jail sentence in a case that received national media coverage.

Manuel figured he could capitalize on the publicity and so he approached Lynne, suggesting a nudist film, Secrets of an Uncover Model (1965). Lynne was enthusiastic. When I spoke to her years later, Lynne remembered: “Manuel was a persuasive and seductive man. He came up to me after my show, and told me that he wanted me to be the star in his new film… But, more than that, he wanted me to contribute artistically as well. I liked that. I was tired of men promising me the world and then disappearing. So, we drove around a selection of South Florida nudist camps, and he let me choose the one I was most comfortable with. You see, I was a dancer, and I had a sexy routine, but I still didn’t know anything about this nudist lifestyle. I found the nudist people to be sweet and friendly, and they invited me to play volleyball with them. I liked it and we had fun.”

Chester Phebus, frequent collaborator of Manuel in the 1960s, remembered that Manuel suggested someone different should be the director of the movie: “He offered the directing gig for ‘Secrets of an Uncover Model’ to his former mentor in the portrait photography business back in the old New York days, Maurice Seymour.

Actually, there were two Maurice Seymours. Two brothers, Maurice Zeldman and Seymour Zeldman, had left Russia in 1920 and settled in Chicago, launching their own studio in 1929 atop the St. Clair Hotel. As the brothers remembered years later, “We were in business together but combining our first names into ‘Maurice Seymour’ sounded better than Zeldman, so that’s how we named the business.” Then, after years of photographing ballet dancers, musicians, and entertainers, Seymour Zeldman legally changed his name to ‘Maurice Seymour’ and moved to New York to establish the company’s New York City studio, where years later he met Manuel Conde.

According to Chester Phebus: “Maurice was a great photographer but he had no experience in directing a feature film. Manny stepped in and made it happen.”

In truth, even Manuel couldn’t save the film: the resulting effort was a mundane account that is part travelogue set on the streets of Miami and part Lynne O’Neill stripping by the Coral Lakes Health Resort nudism camp swimming pool. It was largely unremarkable, but it did make money with playdates across the state.

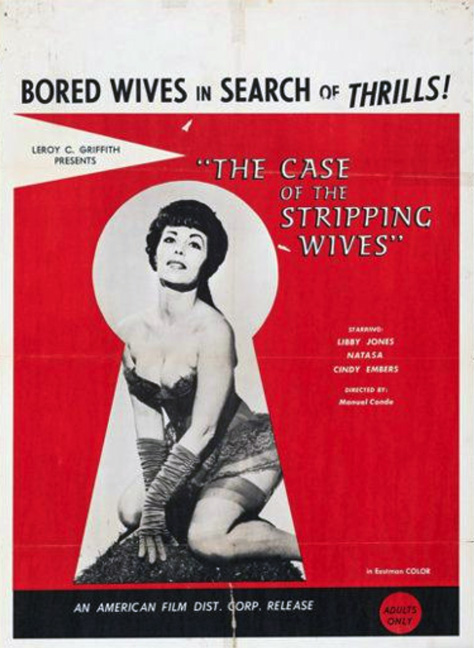

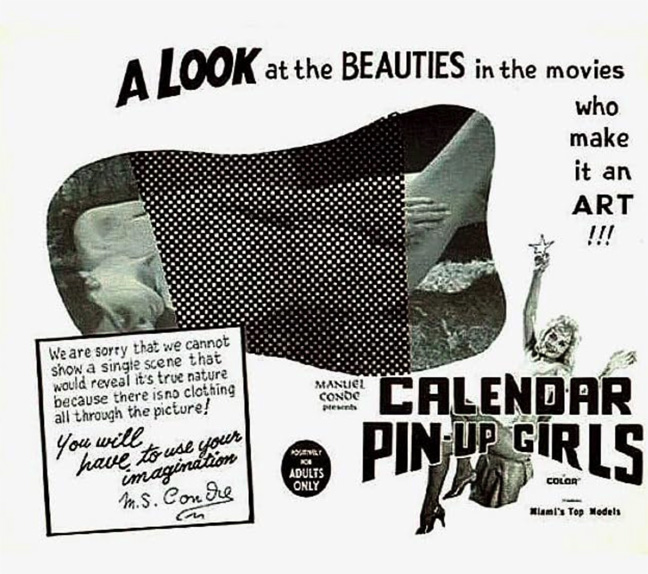

By 1966, Manuel was determined to put himself on the map. He had his eye on directing two films that he hoped would make his name: The Case of the Stripping Wives (1966) and Calendar Pin-Up Girls (1966).

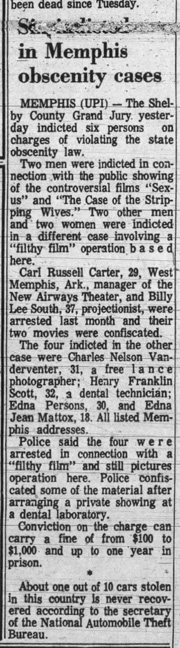

‘The Case of the Stripping Wives’ featured local Miami strippers – including a part for Dolores and jobs for some of her Cuban coterie. It became the focus of a high-profile obscenity case in Memphis but Manuel was untroubled, figuring that all publicity was good publicity. He was proved correct and the film was still playing dates into the 1970s.

‘Calendar Pin-Up Girls’ was a return to the didactic documentary-style nudie film more typical of Conde, depicting the behind-the-scenes process of making a girlie calendar. It took the viewer inside the Miami studio of Conde Productions – including an encounter with “M.S. Conde, nationally known photographer and technical director.” Sadly, it wasn’t the man himself as Manuel remained behind the camera, having an actor portray him, but once again Manuel found a part for his friend Dolores (as Miss September with arms bound by jewelry), as well as other models from the Florida skin-flick business.

The films were virtually one-man affairs with Manuel doing most things himself: he raised the money (invariably from Leroy Griffith), found the talent, wrote the script, shot the footage, edited it all together, and took an active role in their distribution. No matter that his wife was credited as co-director or scriptwriter (using her maiden name ‘Maria D. Maury’) or the editor was listed as ‘Sam Aniego’ (a bastardized version of Manuel’s actual second name), he took full responsibility. Manuel Jr. today says that his mother handled the admin and paperwork. In truth, both films were tame and pedestrian by 1966 standards, with limited nudity, and they didn’t set the world on fire.

Remembers Chester Phebus: “It took Manny some time to figure out how to make a sex film. It was like he was playing catch-up. That was probably because he started off with a Cuban mindset – which was years behind the U.S. in terms of sexual permissiveness. By the time he worked it out each time… the sex film business had moved on and changed again. That frustrated him. He just wanted the chance to make a film with a decent budget – and that eventually came along with Mundo Depravados.”

*

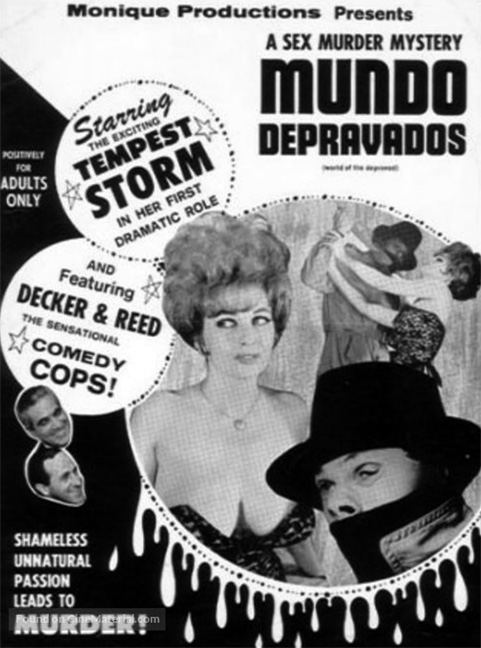

6. Mundo Depravados

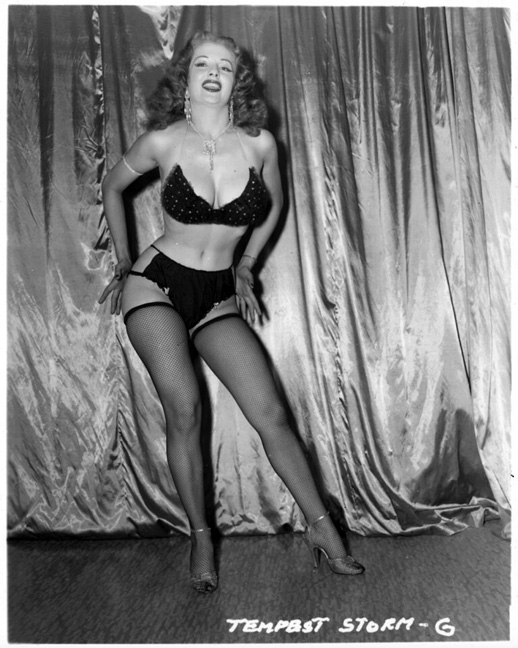

Manuel Conde’s next film, ‘Mundo Depravados’ (1966), was to prove his last in Florida. It was another for Miami theater kingpin, Leroy Griffith. According to Chester Phebus, the story behind the film was more interesting than the film itself: “The idea was hatched one night at a burlesque show at one of Leroy Griffith’s theaters. We were at the Gayety, I think. It was a big night because Tempest Storm was headlining again, and that was always a big night.”

Tempest Storm was one of the country’s best-known burlesque performers of the 1950s and 1960s, a fire-haired dame with impossible curves and an improbable past. She’d been born Annie Blanche Banks in Georgia 38 years earlier on February 29, 1928. She dropped out of school in seventh grade and at 14 was working as a waitress. Her home life was troubled so, to emancipate herself from her parents, she married a U.S. Marine. To call it a short-lived marriage would be an understatement: she had it annulled after just 24 hours.

She married again the following year – at the age of 15. This time the bridegroom was a shoe salesman from Columbus. The marriage lasted six months: “I just left one day. I just had it in my mind to go to Hollywood so I walked out.”

And so, by 1945, at the age of 17, with two marriages already behind her, Annie Blanche Banks was working In Los Angeles as an underage carhop waitress at Simon’s Drive-In. A patron suggested she find work as a chorus dancer at the Follies Theater and, so she did. Three weeks after being hired, she was promoted to the lofty position of stripper. This meant she needed a stage name. The theater manager suggested ‘Tempest Storm.’ As Annie recalled years later: “I asked her if she had any other suggestions. She said, what about ‘Sunny Day’? Ok, I said, I guess I’ll be Tempest Storm then.”

In the twenty years that followed, Tempest Storm became a genuine sensation, a regular performer at the El Rey, a burlesque theater in Oakland, California, but also at clubs across the country. She was splashed across men’s magazines and appeared in burlesque movies, such as Striptease Girl (1952) and Teaserama (1955). She married again – this time to a suitor who bought her a burlesque theater, the Capital Theater in Portland, Oregon – and then she got divorced again.

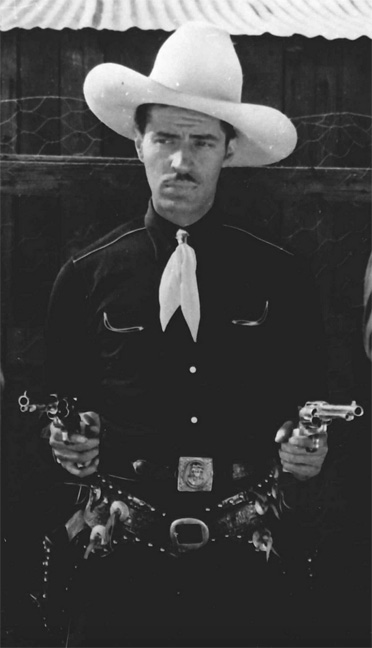

In 1959, she married Herb Jeffries, a suave and seductive film and television actor and popular jazz singer-songwriter. Herb’s life was just as startling as his new wife’s.

Herb had been born Umberto Alexander Valentino in Detroit back in 1913 – which made him 15 years older than Tempest Storm. His mother was a white Irish woman and his father, whom he never knew, was a mix of French Canadian, Italian and perhaps northern African roots. All of which meant that Jeffries was fair-skinned, a feature that attracted racism from both white and black people when he was growing up. To avoid trouble, Herb chose to be white most of the time.

In 1929, he dropped out of high school to earn a living as a singer. He had a smooth, rich voice, and he began performing in a local speakeasy where he caught the attention of Louis Armstrong. Armstrong recommended him to Erskine Tate’s orchestra at the Savoy Ballroom in Chicago. The problem was that Tate fronted an all-black band, so at the audition, Herb pretended to be a black Creole from Louisiana. It worked, and he was offered a position as the featured singer three nights a week playing to black-only movie theatres. Jeffries was a big hit, and he went on to record albums for major labels aimed solidly at the black market.

Herb had film ambitions too, and his first love were the western movies he’d grown up with. He resolved to create a cowboy hero geared specifically for a black audience. Though the silent era had seen a number of films starring only black actors, they had all but disappeared with the arrival of the talkies, so Herb decided to produce sound cinema’s “first all-Negro musical western.”

The problem was that many didn’t find Herb black enough. His dilemma at the time was unique: unlike many actors of color at the time who attempted ‘to pass’ as being white in an effort to broaden their commercial appeal, Jeffries had to go in the opposite direction and darken his skin with make-up in order to be a credible star in a black western. The ploy was successful, and he starred in a string of successful low-budget, so-called ‘race’ Western feature films, aimed exclusively at black audiences, such as ‘Harlem on the Prairie’ (1937) and ‘Rhythm Rodeo’ (1938). They earned him the nicknames ‘The Bronze Buckaroo’ and ‘The Sepia Singing Cowboy.’

Jeffries’ career in film and music flourished. And then in the late 1950s, he met and fell for Tempest Storm. It was always going to be controversial relationship: one of the nation’s biggest female sex symbols, a lascivious stripper from the deep south, engaged to a successful singer/actor from the north, who’d been marketed exclusively to an African American audience. According to the New York Times, the marriage “broke midcentury racial taboos, costing Tempest Storm work” and dimmed both their stars. This time, Jeffries faced the opposite variation of his racial problem: now, he chose to identify as white, stating that his ‘real’ name was in fact ‘Herbert Jeffrey Ball’ on an application to marry Tempest Storm in 1959. Jeffries spoke to Jet magazine, saying: “I’m not passing, I never have, I never will. For all these years I’ve been wavering about the color question on the blanks. Suddenly I decided to fill in the blank the way I look and feel. Look at my blue eyes, look at my brown hair, look at my color. What color do you see?”

In 1966, an unlikely meeting took place in Miami: Tempest Storm – the scandalous veteran stripper, Herb Jeffries – her husband and controversial mixed-race star of black films and music, Leroy Griffith – the millionaire owner of numerous burlesque theaters, adult cinemas, not to mention sex film producer, Dolores Carlos – so-called Queen of the Nudie Cuties, and Manuel Conde – the Cuban emigre’ turned adult film director.

Chester Phebus, Manuel’s friend and frequent collaborator, was there as well, and remembered the evening well: “Tempest (Storm) was getting older: she wasn’t the big star that she had once been – and part of the reason for that was that she’d married a guy, Herb Jeffries, that most people considered black. Anyway, Tempest was still a big draw, and the place was packed that night.

“Leroy suggested a film to Tempest and Herb. Leroy said he’d fund it but he wanted it to be a big film, not another nudist camp thing: a thriller with a plot and lots of characters. He wanted Tempest and Dolores to star, and he wanted Manny to direct. Herb looked pissed: he said he’d made hundreds of films and he should be the director. That annoyed Manny because he longed to make a bigger film. In the end, it was Dolores who acted as a mediator. It was always Dolores…”

Tempest Storm and Herb Jeffries sign contracts for ‘Mundo Depravados’ with Leroy Griffith (seated)

Tempest Storm and Herb Jeffries sign contracts for ‘Mundo Depravados’ with Leroy Griffith (seated)

The compromise reached was that Herb would write and direct the film, and Manuel would shoot it and act as assistant director. The script that Herb Jeffries wrote, originally titled ‘Meet Me Under The Bed’, was a flimsy story of two police detectives assigned to investigate the murders of several young women at a health club. Leroy Griffith secured the presence of other people to appear in it, like Decker and Reed – a double act who’d appeared on The Dean Martin Show – as well as various of Miami’s strippers and nudie-cutie stars, including one Bunny Ware, a favorite of Griffith. Bunny’s main claim to fame was having been arrested eighteen times on consecutive nights in St Louis a few years earlier. Bunny had taken the cops to court, and won a claim of harassment on the basis that her act wasn’t obscene – just “not very good.”

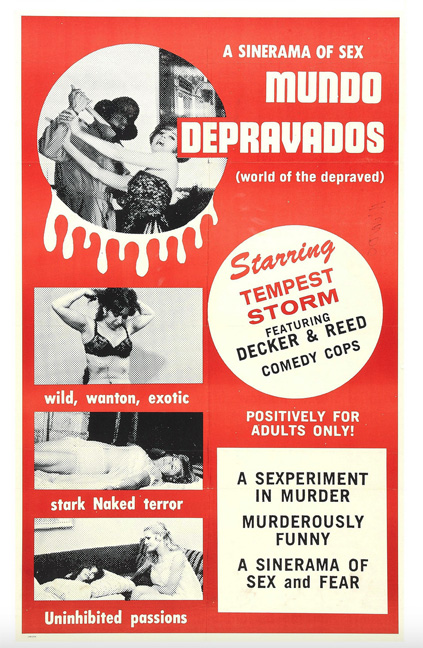

Mundo Depravados was released with eye-catching promo material: “A Sexperiment in Murder – Murderously Funny – A Sinerama of Sex and Fear!”

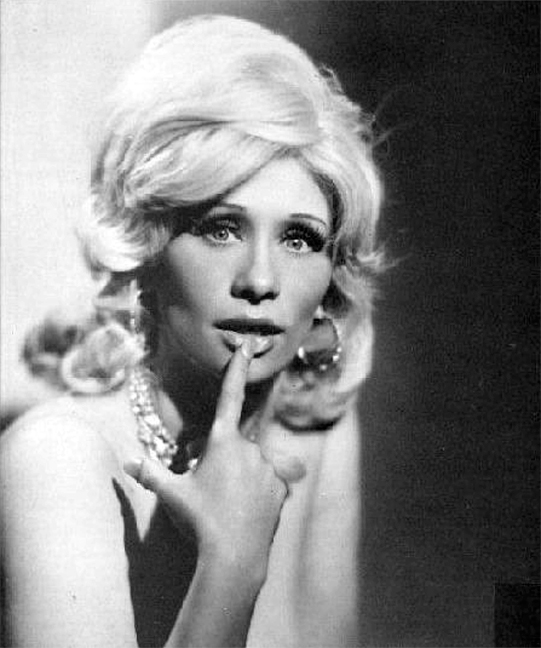

The resulting film, well photographed by Manuel in black and white, is one of the most bizarrely entertaining film experiences you can have. Tempest Storm stars as the stripper whose coworkers are being murdered: she’s a sight to behold, her high beehive hairdo being even more difficult to believe than her acting. The collected Miami strippers offer much bumping and grinding, there are several sex scenes, and Dolores makes a touching appearance as a stripper who meets her end being stabbed by the killer in an alleyway.

Dolores Carlos, in ‘Mundo Depravados’ (1967)

Dolores Carlos, in ‘Mundo Depravados’ (1967)

When I contacted Herb Jeffries a few years ago to ask him what he remembered about ‘Mundo Depravados,’ he was full of enthusiasm for the experience though he admitted the resulting film didn’t set the world on fire: “We had a lot of fun making it,” he said. “But I wished it had done better at the box office. But if life is about having fun, then this was a crazy highlight.”

I sent Chester Phebus a copy of the film, and he watched it for the first time in fifty years. It made him nostalgic for the old days too, and he remembered they were all disappointed the film wasn’t a bigger hit.

Chester believed that perhaps part of the problem was that Tempest Storm and Herb Jeffries’ marriage was coming to an end, and their relationship on set was frosty: “Herb had his mind on other things – mostly the strippers and so Manny ended up directing most of the movie himself, but never got any of the credit.”

I also contacted Tempest Storm before she passed to ask about her memories of the movie, but she recalled little: “Herb and I were finishing our thing, so it wasn’t the happiest time. When we first got married, he adored and idolized me. Of course, I warned him that being married to a burlesque star like me would be difficult. I had a lot of attention from men who came to see my show, and I saw that many of my boyfriends found that difficult to deal with. Herb said he could handle it. But then we got married, and all of a sudden, he wanted me to wear conservative dresses covering every part of my body. Same old story, I guess.”

As for Manuel, Mundo Depravados proved to be the end of his Florida adventure. After a life that had started in Spain before moving onto adventures in New York and then Cuba, Manuel was ready for a new start. He’d had a good time in Florida amongst the Cubans, and the lessons he’d learned in Miami would be useful to him in the next stage of his career. But now, just as he’d done in Cuba, he packed his bags and told his family they were moving west again. Their next stop was Hollywood.

As for Dolores and Leroy Griffith, they were ready for the next Cuban chapter of their lives.

*

Tune in next time for the story of another of the Cuban Immigrants.

This new series shows the quality of The Rialto Report: a sex-business related subject – but told in a factual and intelligent way, wrapped up into an engrossing story, and with a social conscience.

It is a joy to engage in this subject, and not emerge feeling in some way dirty. A rare feat indeed.

I feel dirty, but I’ve dealt with that. 😉

If these “marginal” films had no value, they wouldn’t be championed today.

Thank you so much Chris!

This site is the soundtrack to my Sunday nights – and that makes Sundays my happiest night of the week.

We really appreciate that Tony!

Please don’t ever stop with these articles!

Thanks.

Thank you Yarris!

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work

Thanks as always Jeff!

It’s staggering the number of crazy movies made in Florida. Your impeccable research helps to ALMOST understand why. 🙂

Thanks JWP!

Artists to my mind are the real architects of change, and not the political legislators who implement change after the fact. – William S. Burroughs

Journalistic art of the HIGHEST influential level. This is stunning, thought provoking, and throroughly sexy.

The added characterizations of Tempest and Herb just complelety blew my Sunday state of mind. As a very young woman, I dipped my toes in the Golden Age pool and found myself at the doors of the Mitchell Brothers O’Farrell Theatre (San Francisco, CA).

The Brothers’ beloved “Tempie” was a show stopping Feature Act who never failed to pack the house. Her charisma, kindness, and genuine care for her “little girls” is still a big part of who I am.

For one of her stunnning appearances, “Tempie” talked the Brothers into featuring her and her daughter (Herb’s child) on stage together. The show was a complete sell-out and I remember watching from the wings in utter sensory overload… Trying to take it all in while at the same time wondering why I couldn’t have a Mom as fuckin’ cool as Tempest Storm.

Love the Rialto Report beyond measure…. Totally concur with Yarris: I’m with Yarris… “Please don’t ever stop.”

– Thelma

We so appreciate this Thelma!

Excellent!

Thanks CJ!

Intelligent, thoughtful, and insightful. It becomes easy to take this for granted but the standard of research here is light years better than anything available elsewhere… much of which is frankly embarrassing.

Keep up the great work!

Thank you so much Pauline!