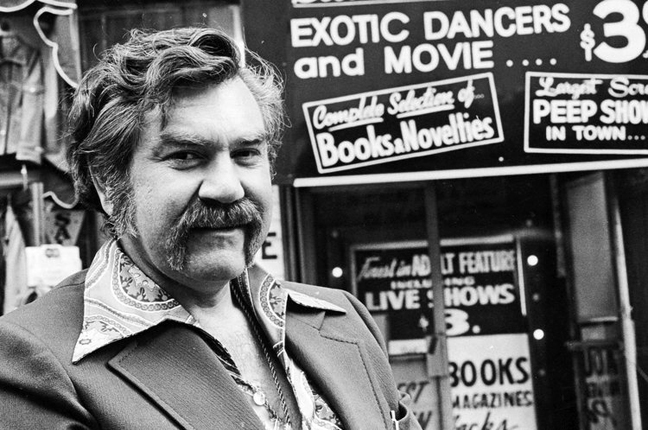

Arthur Morowitz may not have been a famous director or star of adult films, but it could be argued that he was more important than that.

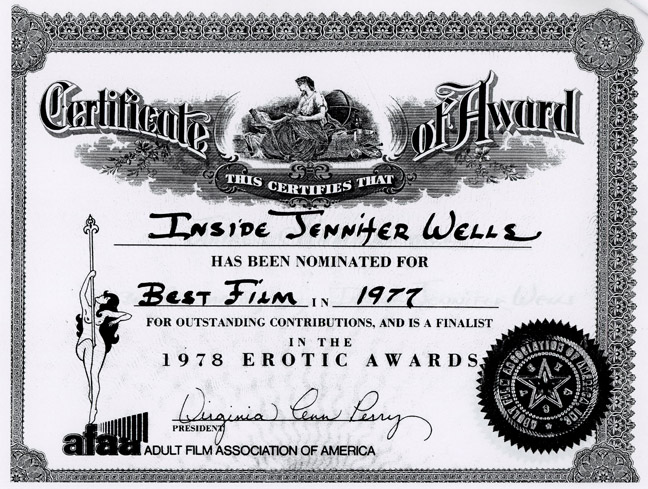

In 1965, Arthur founded Distribpix, one of the first New York adult film distribution companies in the country. Arthur and Distribpix were responsible for distributing Joe Sarno‘s films as well as those of many other rising adult film directors, in addition to fighting court battles, producing high-budget box office hits such as Inside Jennifer Welles (1977) and Inside Seka (1980), and helping organize and coordinate the industry – thereby giving it much-needed respectability.

His later business interests expanded to owning a series of adult theaters in New York and founding Video Shack, one of the country’s first video stores – before he branched into other fields such as wrestling videos and his Champion Stamp Company, which specialized in collectible stamps and world currency business.

Arthur is one of the success stories of adult film. A natural entrepreneur, he was able to understand the business dynamics of the film market, and exploit them shrewdly. So much so, that when I asked Gloria Leonard about him, she commented that if she ever wanted to kill herself, she would just have to jump off Arthur’s wallet.

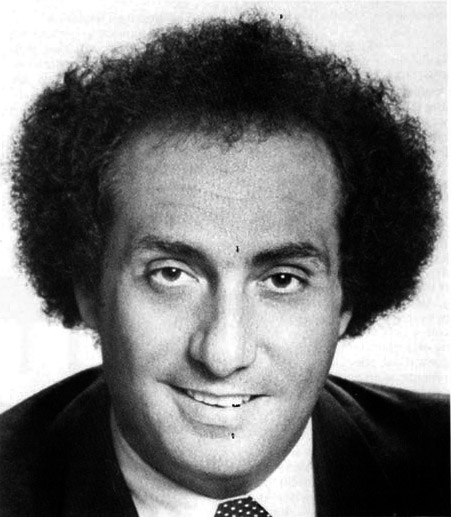

In the early days of the internet, though I hadn’t spoken to him, I’d seen a picture of him online which showed him to be a tanned, jovial, larger than life figure.

And then in 2004, I was in an airport departure lounge, traveling back to New York from Memphis, when I became aware of a figure in one of the chairs. He was fast asleep and drawing a modest amount of attention to himself by breathing heavily (aka snoring). When I looked over, I realized that the dormant giant was Arthur Morowitz, who I later learned was returning home after a stamp convention.

After he woke, I introduced myself and told him that I’d interviewed a number of people who’d directed or appeared in films in which he had been involved. He was bemused as to why I was interested in actors or filmmakers: he said that if I had an interest in, say, banking, I wouldn’t speak to the people who worked in the office cafeteria. He said that the story of adult film can only be told by those who owned the means of production, of distribution, and of exhibition.

When I asked him if I could interview him about his role as the Godfather of New York adult film, he laughed at the description. He agreed, and over the next years, I interviewed him several times about different parts of his career.

I filmed some of the interviews, and when I looked back at one of the release forms that he had signed, I noticed that he had written: ‘Arthur Morowitz, Godfather of New York adult film. (And cafeteria worker.)’

Arthur died on September 11th, 2023.

These are some highlights of my conversations with him.

——————————————————————————————

1. Arthur Morowitz – Beginnings

Let’s talk about the first years of your life.

Not much to tell: a simple New York Jewish upbringing on Long Island. Nothing remarkable. I did well in class, and was at law school when I ended up in the dirty movie business.

You saw the rise in adult film business in the 1960s – and spotted a commercial opportunity. What was happening?

Three major social changes: Consumer desire. Legal progress. And economic changes.

What do you mean by economic changes?

In the post-World War II years, the population in America started to leave the big cities and move to the suburbs. And when that happened, the large theaters – that had played most of the movies up to that time – suffered and started to face competition from smaller, more efficient operations.

At the same time, Hollywood went from releasing films using a roadshow concept, meaning that one big movie played in one city at a time for many weeks, to a wide area where they started putting out a new film in a thousand theaters at one time and just played it for a week or two. So that created more competition for the downtown theaters.

In addition, the population didn’t want to drive into a city after having worked there most of the week: they didn’t want to pay for gas for their car, an expensive restaurant, and the babysitter for all their travel time as well. So people started to go to the movies near where they lived, and that gave the theaters in the suburbs an advantage over the ones in the city.

These factors combined to create problems for the old-school, large theaters.

Why didn’t the inner-city theater owners just re-purpose the buildings for something else?

Movie theaters are not built for quick change. They’re elephantine buildings, they’re very specific in terms of being built for one purpose. They have shorter fronts than they do lengths: that means that if you try to chop them up into small stores, you get small, long, skinny and inefficient stores. It’s also hard to raise a demising wall when you’re going up 60 or 70 feet, especially if you have multiple balconies – and some of the old theaters did. Plus, they also had extensive plaster work and gargoyles and all that kind of ornamental stuff that tends to fall if you’re not careful, so they were heavier maintenance buildings.

It wasn’t easy to change their purpose.

What effect did adult films have on these theaters when they came along?

It was very positive. The adult films provided fuel that could run these old theaters in city centers.

The people that produced the adult films didn’t need a lot of money – because their budgets were so low. A Hollywood studio would want a 4,000-seat house. An adult film producer only needed about 300 seats to make his money back.

And that’s because those theaters would grind all day long: they’d open at 10:00 in the morning, close at 12:00 or later at night, and they’d run the films continuously non-stop. In other words, if you walked in the middle of the feature, who cared? Customers didn’t have wait for a film to start or for it to end – they could just walk in and out whenever they wanted. Many of the audience did exactly that.

And the advantage of all this was that the operators continually had a reliable, steady flow of funds.

*

2. The Birth of Distribpix

So if that was the background to the business, how did you get started?

I started in 1965 – with what was called an Investment in States Rights.

That doesn’t exist anymore, but what happened was that when somebody produced a movie, it would be sold off through exchanges. These exchanges were formed by arbitrarily drawn lines around the country: for example, the New York Exchange was the whole state of New York plus the northern half of New Jersey. The southern half of New Jersey was serviced out of the Philadelphia exchange. The twelve western states were all rolled into one exchange at one point. I think there were about a dozen exchanges across the country.

So people would produce a movie and sell it to a group of independent distributors rather than a major studio. The independent distributors would then sell the product to local theater owners. And that’s what happened with us: we were presented with an opportunity to buy States Rights to what was then an adults-only film.

How was it classified as an adult film?

The rating system didn’t start until 1968, so there was no X, R, XX, XXX. This film was just ‘Adults Only.’

What was the film?

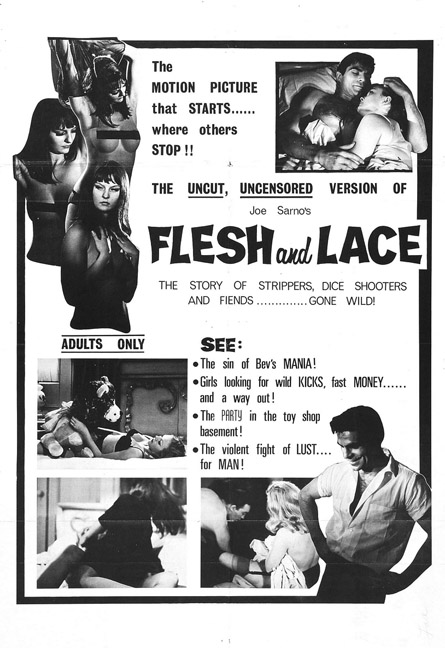

Flesh and Lace (1965). It was an early Joe Sarno film.

Where did you get the money for the investment?

I had a partner, Howard Farber, but the investment was my Bar Mitzvah money, or what was left of it. It wasn’t too much money, but it was enough to make an investment.

What did you do next?

The person who sold us the States Rights hadn’t sold us the advertising campaign… he hadn’t even created one. That’s the posters, the one-sheets, the stills… all the things that we learned you needed to sell a movie.

When did you realize that?

Only after we’d bought the rights. We didn’t know what we were doing, so we got thrown into the pool and had to do it all ourselves. We created all the stuff for a small area where we were selling the movie.

In actual fact, the seller then used our materials for a bigger area. But it wasn’t so bad, it was a learning experience. It was like going to the race track for the first time and picking nine winners out of nine races: we did everything wrong, but we still managed to come up with the right formula to sell the film successfully.

Where did ‘Flesh and Lace’ play?

It opened at the Tivoli theater in Manhattan – and it broke the house record at that time. In one week, we got back 75% of the money that we’d invested. Everybody was congratulating us, saying this would run forever.

How racy and explicit was the film for 1965?

In terms of total nudity, ‘Flesh and Lace’ contained… perhaps three minutes. And, of those three minutes, two and a half were shots of a woman in a sheer negligee. Then there was a nude scene with a woman laying on her stomach – and you could see her rear end: that lasted perhaps ten seconds.

I’m sure that was the total extent of the nudity.

What happened after the first week’s engagement?

We thought we were kings of New York. And then disaster struck.

In the second week of the booking there was a citywide blackout: it was considered the first blackout in the East. We’d written such a poor deal with the theater that we were actually guaranteeing them a minimum amount of money – and this blackout meant we were risking paying them a lot of money that we hadn’t made.

The news on television kept announcing that there might be more blackouts. The first blackout was Tuesday and we had to give notice by Wednesday if we wanted to take the film out of the theater the following week. In the end, we chickened out because we were too afraid to stay in – so we gave them notice and cut our losses.

Overall, we just about got the rest of our money back so it wasn’t too bad – but it taught us a lesson.

The experience didn’t put you off?

No. In those two weeks, we’d made as much money as we put in, and we’d had a whole territory to ourselves. It was very exciting. So we decided to stay in the business. We formed a company called Distribpix.

You went from distributing movies to producing films pretty quickly – how did that happen?

The guy who sold us ‘Flesh and Lace’ saw the money we made, and he said, “Why am I selling movies? I should be distributing like these kids.”

As a result, he wasn’t going to sell any more movies to us, so we took the decision that we had to produce a movie. We got hold of Joe Sarno, the same guy who’d directed the first movie, and made a deal to produce his next one.

What were your first impressions of Joe?

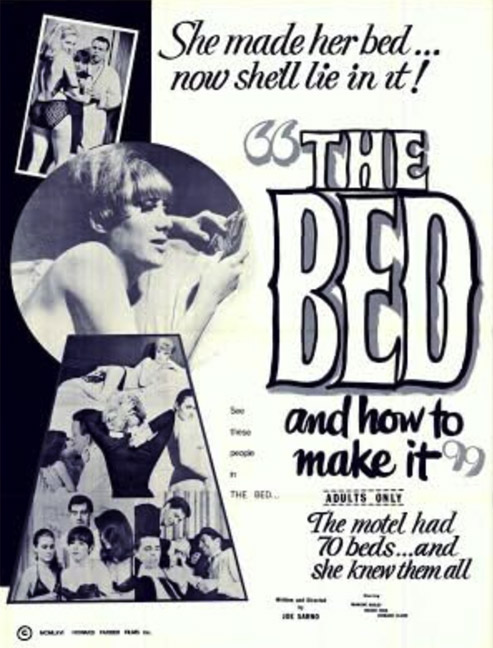

He was great. He was kind and patient enough to work with us and teach us how to do the job. He was extremely competent, and together we made a nice movie called The Bed and How to Make It! (1966).

Arthur Morowtiz (center) with Joe Sarno (right) and Howie Farber (top) on the set of ‘The Bed And How to Make It!’

Arthur Morowtiz (center) with Joe Sarno (right) and Howie Farber (top) on the set of ‘The Bed And How to Make It!’

*

3. Running a Sex Film Business

Who were your contemporaries – the people you encountered in the adult film business when you started?

Most of the people had come in from the carny or the burlesque business – people like Dave Friedman. They were older and a completely distinct breed of person to us.

Howie and I were different. We were called “the kids” for years – up until we were in our 40s! We were an exception when we started. Nobody started at our age at that time. It was an old man’s game until that point.

Then there was Chelly Wilson. She had a lot of power in New York because she ran the theaters with Greek names: Venus, Adonis, and so on. She knew the ropes long before we got involved. She took advantage of us by charging us a ridiculous price to advertise our first movie. Typical Chelly deal! But we learned from the experience.

You financed your money by rolling profits into your next films. Did you ever invite external investors?

No, we started with a couple of investors and realized very early that was a mistake. The investors were never happy, and they didn’t understand the business, and it just wasn’t the way to go.

Distribpix was unique: we were a distribution company as well as a production company, so we handled lots of other people’s films.

The advantage to this was that our films never had the same look as each other: a theater owner could book four of our products in a month and they never would look the same, whereas if you dealt with just one producer and tried to book four films from them, they’d all have some similar characteristics because people did things a certain way.

So at our company, we had a great advantage in selling because we had more variety and we were smart enough to know our product well enough to mix it correctly.

How concerned were you about potential legal issues because of the sexual content of your films?

There were always legal issues. Probably the reason we were able to have as much nudity in our first film was that New York State had abolished the censor board in 1965. There were still censor boards in other parts of the country – Chicago had one for many years after that, and I think Baltimore’s censor board lasted even longer than Chicago.

Times were changing… nudity wasn’t as frightening a concept as it had been… The Hays office, which was the National Office of Censorship, was long-gone. Hollywood movies were becoming more daring which led to society becoming more daring. Or maybe it was the other way round.

Still from ‘The Bed, and How To Make It!’

Still from ‘The Bed, and How To Make It!’

What was the process to get a film approved by a censor board?

We’d just submit the film. Sometimes if we had a local distributor then we’d go along and make the case for the film, but it didn’t much matter: the censor would often come back with 30 pages of ridiculous cuts, and you were lucky if you wound up with anything more than a short film…

The good news was that if you passed the censor board then you never had to worry about it again. The bad news was that you rarely ever passed the censor board without a big fight.

Were you concerned about getting arrested?

Well, at any given time you risked getting a prosecutor who wanted to throw you in jail… which was never fun. And it happened to us from time to time. There is nothing that makes a prison guard happier than him telling you to spread your cheeks. He’d be so pleased that I was surprised he didn’t bring his family along with a picnic to watch. You have to deal with some of these idiots in all walks of life.

What did your parents think of your new career?

My mother didn’t want to talk to me at first because she couldn’t understand why was I was going into business making dirty movies. But after she saw ‘The Bed and How to Make It!’ at a screening, she felt it was nothing less than what was already playing at her local Manhasset cinema. She said it was a very good movie and she enjoyed it, so I was redeemed.

Fortunately, she never went to see the hardcore films we made that came up later on…

How about your friends? What were their reactions?

Our friends thought it was great and bugged us to invite them to the set. So we’d get them to be extras and sit for hours in a nightclub for background, and that killed their interest. Yeah, there were some naked girls, but they said, “I’m not going to do this anymore – it’s too slow.”

You said at the beginning of our conversation that consumer desire was changing: can you expand on that?

There was suddenly a much greater need from the suburbs for more daring and exciting product. And at the same time, there was a greater awareness of film as an art form – an awareness that hadn’t existed before: schools started to have film classes and they began to teach film as a proper subject. For the first time, people realized that film was not a God-given gift to the Hollywood community… and instead anybody could get into it with a camera and a little money.

So all these factors came together and created a great demand… and where there’s more need, you get more product. Our company led the pack because we could fill the demand for that product.

As you made more of these films, was there a formula or a standard template?

Sure, you developed an understanding of what worked and what didn’t. But it didn’t guarantee that you were going to get it right every time. I mean what made ‘Gone with the Wind’… ‘Gone with the Wind’? There were always many different variables so it was hard to know exactly what would be successful.

You built a good relationship with Joe Sarno right from the beginning.

Yes. Joe was a good man. He was good for us, and we were good for him. It was an important and successful synergy.

After ‘Flesh and Blood’ and ‘The Bed, and How to Make It!’ came Skin Deep in Love (1966), Anything For Money (1967), All The Sins of Sodom (1967), Vibrations (1967).. and so on. We were still working with Joe twenty years later.

Joe was a good filmmaker. He was serious about what he did. There weren’t many directors out there like him.

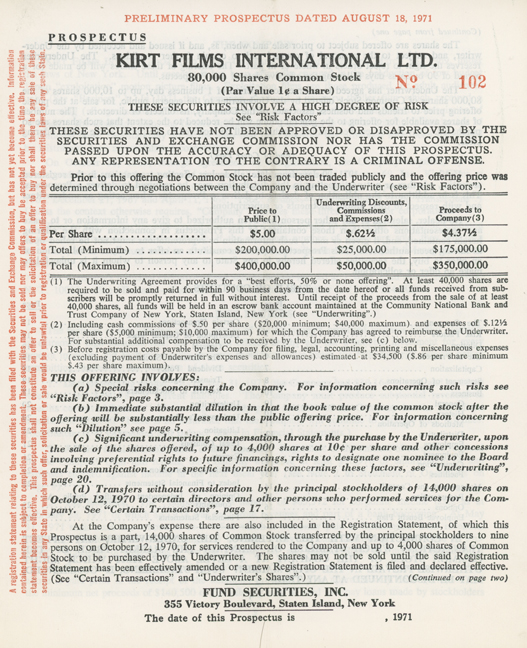

Aside from Joe, the filmmaker you worked with most in the late 1960s and early 1970s was Leonard Kirtman, who made films through his company, Kirt Films. You distributed a lot of his films. What do you remember about him?

Leonard Kirtman’s only genius was that he had us as distributors. He was a cheap sonofabitch, and he made more adult films than anyone else at the turn of the 1970s. He set up Kirt Films and sold all his films through us.

He was hardworking, I’ll give him that. He would shoot four or five movies over a single long weekend. He used the same cast and shot them at his townhouse on West 71st St on the Upper West Side.

There would be no way of selling his stuff stand-alone films because they were terrible, but fortunately for him, we had lots and lots of other movies to sell as a package with his. So he could get away with it because we knew how to play em’ right: we did the campaigns, the publicity, the marketing, everything. He was lucky he had people like us, that were hardworking and honest, that could keep pushing the product for him.

To be fair to him, his movies were so cheap that you could never lose any money with them. He was very, very cheap. Most of these films have never been released on home video or DVD or anything because the quality was so poor. Titles with cheap puns like Around the World in 80 Ways (1969), Doggie Bag (1969, Catch 69 (1970), Four Play (1970), My Swedish Cousins (1970), Open Air Bedroom (1970). I can’t believe that I can remember still the names… there were tens of them, a hundred even.

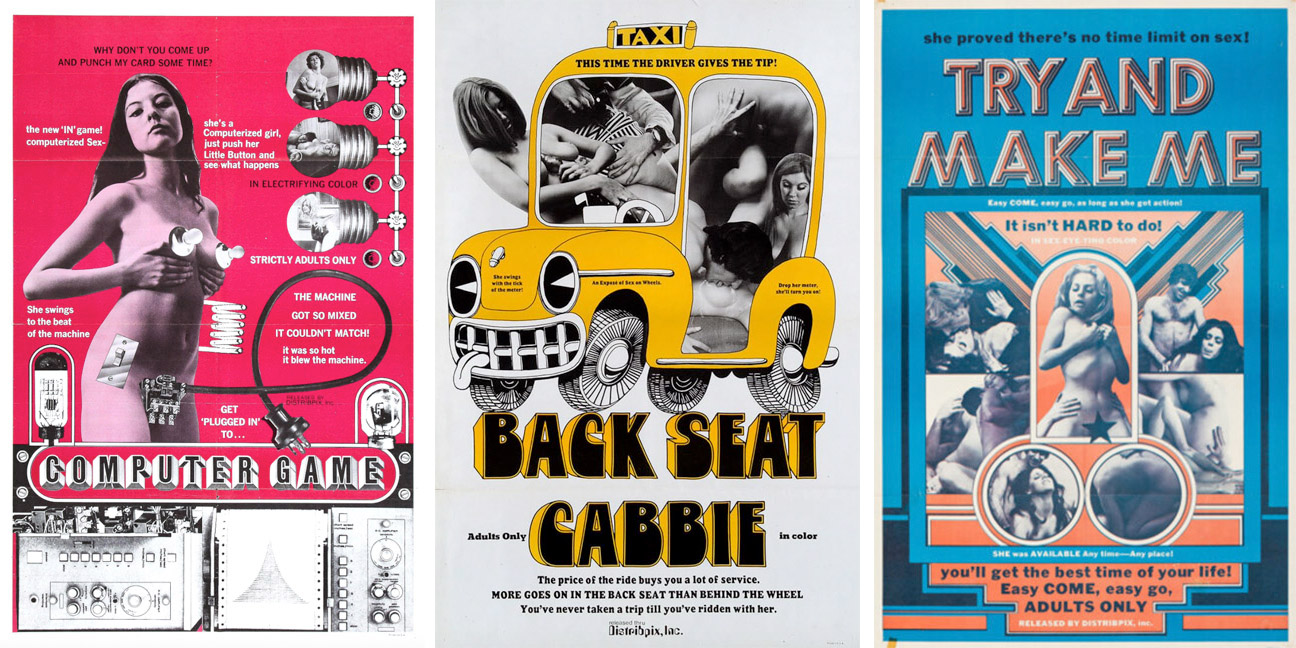

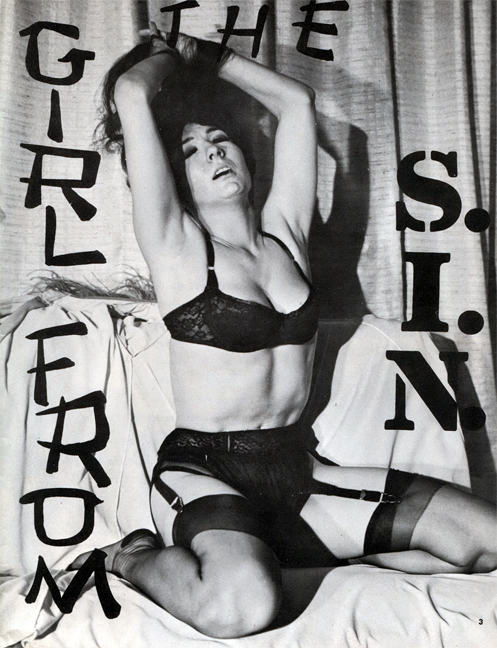

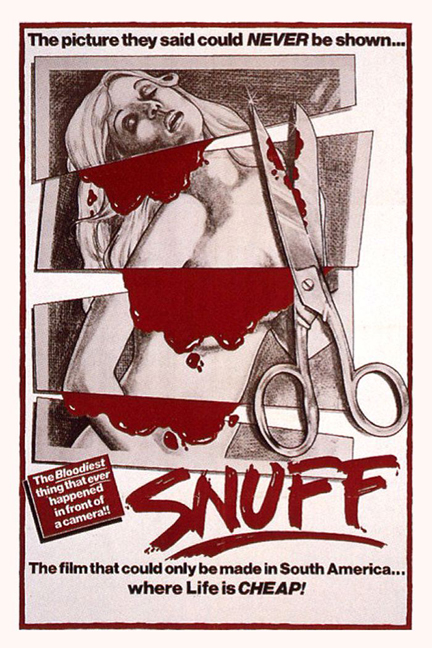

Selection of Kirt Film one-sheets – distributed by Distribpix

Selection of Kirt Film one-sheets – distributed by Distribpix

I see Lenny from time to time.

I’m sorry… that must be difficult for you. (laughs)

Who are some of the main filmmakers that you worked with in that period?

It was a small world, so I knew them all. Ron Sullivan, Graham Place, Don Walters. It was a tight group of guys.

Another was Howard Winters (aka Cecil Howard) who I interviewed recently…

I’m sorry to hear that. You’ve really had a tough time. (laughs).

Many of these were people without much talent… Their films at the beginning were all just excuses to show naked bodies.

What was your working relationship like with your filmmakers?

The best thing the filmmakers had going was our company. Once you made one film with us you were part of our repertoire. In other words, we’d produce it if you were capable of finishing it, and we’d give you a fair price for it – but you’d never get rich.

So they were pretty good with us, we had a nice relationship,

How much did you intervene into their filmmaking process?

All the time! We had to sell the films so I didn’t want them to make anything I couldn’t sell! I had a good handle on what I could sell a film for, so I didn’t want a filmmaker to exceed that. A lot of directors were making these films to learn about filmmaking – so they wanted to try all these new ideas. That was fine – but there had to be a price limit to it.

I’d tell them what we were looking for: if I thought somebody was putting too much money into a budget, I’d say “Listen: you’re overdoing it because it’s not going to make us that kind of money back. Cut back the budget or go somewhere else.”

So it was something we were very careful with, and we worked very closely with the directors.

You made and/or distributed many films in the late 1960s: how profitable were you?

The busiest years we ever had were the four years from 1968 through 1971: that was the last gasp of the soft-core era. We produced or distributed fifty to sixty new films in each of those years. And most of them were Lenny Kirtman cheap efforts.

It was a fairly steady business. It didn’t have big ups and downs. We didn’t have the big theatrical releases. If a success came along, it could have been because it had some detail that people thought was better, but most of the time, the increased in revenue was more to do with the timing rather than the picture itself.

The result was that it was a reliable business that paid the rent and gave us a good lifestyle.

What kind of people did you get to appear in the films?

At the very beginning, in the mid-60s, we were working with a lot of proper actors and actresses, people who had acting experience.

Later on, as the films became more explicit, we worked with a lot of people who had pretty bodies that were not too concerned with acting: they just liked the idea of doing it, or they liked what they looked like, or they wanted to be featured in a magazine like Playboy… or they just wanted the money. So the mentality of the people changed as well.

Can you describe what it was like to be on one of your film sets during this time?

I’d venture to say that nobody worked on a better set than we had.

After a period of time, we got the routine down to a fine art. It took a while to get there, but we worked out the best ways to do it. We started at eight in the morning, and we finished at five each day, rarely did we run over. On other films, you had guys shooting 24 hours a day and killing themselves.

We had basic rules: we didn’t allow beer on our set, and no drugs. We wouldn’t even let the crew drink a beer with lunch. The point was that you never knew anybody’s limits: a beer for one guy might be the same as ten to another guy. We had a job to do and we had to stick to the budget. Afterwards I took everybody out to a bar, but during the shooting, I was firm. I used to say, “If you worked at a bank, would you have a beer can at your desk?”

The other part was that they usually got paid by the day, so if they had an eight-hour day, they got the same as if they were staying for a twelve-hour day. They all respected the fact that we worked hard and we got it done. We didn’t take advantage of anyone because we scheduled a shoot accurately so we could get it done with a minimum amount of aggravation.

Arthur Morowitz and Howie Farber (seated) as extras in ‘The Bed and How To Make It’ (1966)

Arthur Morowitz and Howie Farber (seated) as extras in ‘The Bed and How To Make It’ (1966)

*

4. One Pubic Hair at a Time: Softcore becomes Hardcore

As the 1960s came to an end, the films became increasingly risque’. Did you feel pressure to make your films more and more sexually explicit to keep up with, or keep ahead of, the competition?

Basically, it was an industry competing with each other one pubic hair at a time: somebody showed one hair, the next guy showed two, the next guy showed four, the next guy showed eight… and before you knew it the screen was covered with it. We were part of that progression, and we couldn’t afford to fall behind.

But there’s a misconception that the sex film market was just one homogeneous place with one homogeneous standard.

In actual fact, it was a varied market: in some places, our product led the market, in other places, the market was ahead of us. And certain areas moved faster than others. The big cities generally moved faster and were more progressive than the suburbs – but that wasn’t always the case because sometimes in suburbia you had a theater owner who was well-connected in town and nobody really cared what he played so long as nobody was exposed to anything on the street… so they could play anything. Other times, you could have a very small town in suburbia which didn’t care about community standards – and they would play a picture as hot as they could get.

Marty Hodas, who introduced peep shows into Times Square, is often credited with bringing hard core sex into New York for the first time in the late 1960s. Did your path ever cross with his?

(Laughs) Yes, I remember Marty Hodas because he wound up working out of the same building as us.

He started out with peep machines – you went into an adult bookstore, put a quarter in and played a loop of film for about 2 minutes and then you had to put another quarter in, and then another quarter after that. I’d seen the concept out in California, having traveled back and forth quite often in those early days because California was a good market. I came back and I said to Howie, “This peepshow thing is happening, let’s check this out.”

So we went down to some of the amusement companies that made the machines, and after a few meetings we just said, “Oy, it’s too difficult, the machines break, the film strips are too fiddly, it’s all too labor intensive.” That was probably the biggest mistake we ever made because Marty went on to make fortunes of money with his peep empire.

Do you remember when explicit sex started to appear in feature-length adult films?

Sure, it was like the moment you first saw a man walking on the moon.

It was defined by three factors: erection, penetration, and ejaculation: if you had any of those three you were probably making hardcore, and if you had all three you were definitely in the hardcore field.

At first it was in the loops. A girl could walk into a room, take her clothes off, spread her legs, pretty much put her toes behind her ears – and everything was fine as long as nobody touched her. Then after that, men started to appear: they could be in the room but you couldn’t show them getting hard.

It kept developing like that. By the start of the 70s, there was nothing left to the imagination. There was nothing left to uncover! I mean, I guess you could shoot fluoroscopes – X-rays with real-time moving images of the interior of a body – but you couldn’t see anything more!

But it wasn’t just an adult film issue: mainstream films from Hollywood were becoming more racy and pushing the envelope too.

Was it a moral dilemma for you whether to make hardcore films?

No – it was purely economic. Society just kept pulling ahead of us so we did what we need to in order to keep up. We had no moral issue with that.

Some of the people found the change more difficult. Take Joe Sarno for example: he hated the fact that films had become hardcore. He didn’t want to change. He wanted to keep making his softcore melodramas forever – and to give him his due, he did that for longer than most others. In the end, he realized he had to change and that there was no softcore market left – so he became a hardcore filmmaker.

As you mentioned, the switch to hardcore didn’t happen in every geographical market at the same time, so how did you deal with that?

It was a problem. We were producing hardcore movies to some markets at the same time as we were selling soft-core somewhere else… we had to be aware of the difference and had to keep detailed records of what we were doing.

How many prints would you strike for each film?

We were limited to a number of prints economically because each print had a cost, so we moved fairly slowly by necessity. This meant we didn’t cover the country with a single movie in a short period of time. Generally, it might take two years for a film to make its way around.

What was the amount of a typical budget for a film in the early 1970s?

You’re talking about a 60–70-minute color film. Typically, that was around $10,000, maybe up to $20,000. Later on, we went much higher, spending over six figures on certain of our hardcore movies.

But in the early days, it was around $10,000. I actually knew a guy who said he could make a 60-minute film for $4,000 dollars. I knew my budgets pretty well and I didn’t believe he could do it, so he proved it to me. But it wasn’t a sustainable model: it meant doing a lot of things that you wouldn’t normally want to do – like scavenging garbage pails outside of editing rooms and using 35mmm full coat film stock that had been recorded over.

We learned that there were ways to reduce costs: for example, laboratory costs were one of the most expensive areas. The labs would charge you $1 a foot for a timed answer print, and an hour-long film was around 5,000 or 6,000 feet. When they developed a film, they used a certain degree of lighting. If your cameraman was good, you could use a one-light print and it’d be perfect – and that didn’t cost much – and most of the stuff we didn’t need to do anything else. But if there was scene that needed some correction, we gave the guy a little extra and he did the rest of the job. So it was a question of being able to think on your feet and negotiate a good deal. Much like any business.

What was the type of distribution deal you would strike with the theaters?

At first, they paid you a percentage of receipts. That rewarded the better films – because more people would go and see them. But then that changed, and they started paying a flat fee instead. This meant it didn’t matter how good the movie was, you weren’t going to get any more money for it. So it was even more important to keep a lid on the budgets.

Would you make money on all of your films?

You figure you could always get your money back within 12 months after the first play date. And then you’d double your money again in the next twelve months – and then the residual would probably earn you one more go around over the years. So if you put out $10,000 for a movie, you didn’t necessarily get it back quickly, but over time you’d earn back three times your investment.

It was good business because it was fairly safe and predictable. Sometimes you had a hit and so you’d earn even more, but those were rare exceptions.

How important were the old theaters in Times Square to you, given that you had built a national distribution network. What role did it play in your business?

Times Square was pretty unimportant. The adult theaters in Times Square had been run by a fellow by the name of Bingo Brandt: they were part of the Brandt theater circuit. Bingo was the young guy in the business, and he wasn’t a great promoter. If you were stuck for a day, you’d play your movie with him. But there were other people in New York that did a better job in promoting them. So Times Square became second run very quickly.

The Times Square houses were less competitive because they were much larger: all of the sudden 199 or 299 seat theaters opened, and they had advantages in terms of getting public assembly licenses. They were better suited to us.

In addition, Howie and I started to take long leases on theaters so we could exhibit the films that we had a piece of.

*

5. ‘Deep Throat’ – The Explosion of Hardcore

In 1972, Deep Throat was released – and it was a huge success. How did it change the business for you? Was it a watershed event even for more experienced producers such as yourselves?

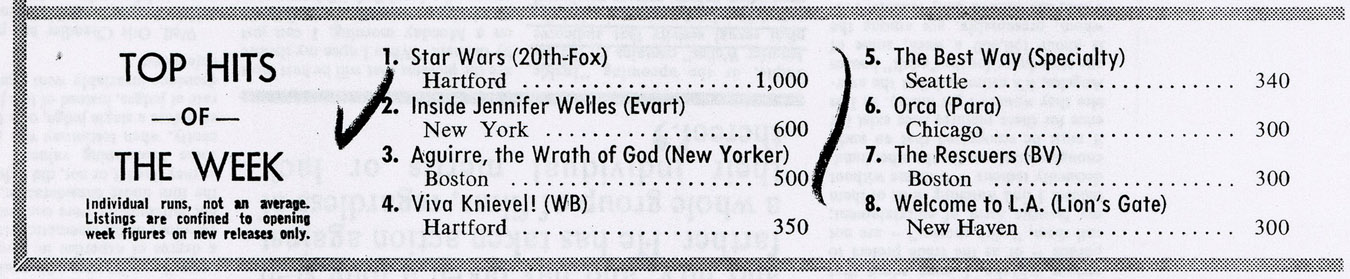

For most people, seeing ‘Deep Throat’ was like the first time you ate Chinese food: it was like you’d just discovered something new, even though it had been out there for 5,000 years. For someone who’d never seen an adult film before, ‘Deep Throat’ made a tremendous impact. But for us it was business as usual – except that the audiences were bigger so we made more money.

If you’d been making sex films for a while, what made ‘Deep Throat’ the sudden breakout hit?

I have a theory as to why ‘Deep Throat’ was successful: people said, “It was a big hit because it was the first explicit one”. Others said, “Oh, it was successful because it was the first funny one.”

Well… it wasn’t the first explicit X-rated film, nor was it the first funny one. But it was the first film that took the concept of fellatio from a quantitative judgment to a qualitative judgement: the question was not “Does she suck cock?” but it was “How well does she suck cock?”

For men and women, that was big deal: you no longer had to say to your girlfriend, “Honey would you give it a kiss?” but instead “How well can you kiss it?”

I think it changed women’s minds that this was an acceptable practice, and they’d better get good at it. I think that was the big change.

What new challenges did hard core films bring to your company?

In terms of the films we made or distributed, we didn’t change much. I was more concerned about what was on the outside of the theater than in the inside. That was where we would get complaints from the local community.

In New York, we worked closely with the Mayor’s office on obscenity. If anyone complained that the theater had something offensive on the outside, the police called us and we had to get it changed immediately. We always did what we were told, and always cooperated. For example, if, by mistake, there was a lobby card with a woman who was topless or in a state of undress, we’d put tape over her breasts or take the card down.

Did that hurt business?

Not at all. It didn’t matter. After a while, the customers knew what was inside: nobody ever walked into one of our theaters by mistake.

Distribpix had become one of the most successful adult film companies. What did you do to consolidate your market position?

For many years we actively advertised in the regional and local newspapers next to the mainstream blockbusters.

We created a brand identity: we had a company called ‘Sweetheart Theaters’, and we created our own monthly brochure showing what was coming up in all the theaters. It was pocked sized, so you didn’t have to walk around the streets with it in your hands, and it never got thrown all over the streets because it would fit in your top pocket. It gave you the names and phone numbers of the theaters, and it gave the movie schedule.

Eventually the newspapers stopped taking your ads because they wanted to distance themselves from sex films.

Did the lack of ability to advertise any more create a problem for you?

A little, because you’re always better off with the ability to advertise – but the ads had become extremely expensive. A small ad could cost thousands of dollars so we saved a bunch by not doing it. By then our audience knew what we were about anyway.

What was the demographic for your films now that they were hardcore? Was it still the single man with the classic raincoat stereotype?

We always had excellent audience, very informed, not what you’d think, and we never a problem with any of them. We had a strict policy of “21 or be gone” and were rarely ever challenged by young people trying to get through the door.

At the very beginning, it had always been single men, I’d say their average age probably was 35. But when films became hardcore, the demographics changed. There were men who were going for education: they had lived their life a certain way, a repressed, sheltered life – and it wasn’t working for them. They used the films to provide them with sex education because people had no other place else to get it.

At the same time, more women were becoming interested. I remember a few times each week, a woman would walk up to the box office and say, “Is this a dirty movie?” and I’d say “Yes”.

She’d shout down the street, “Honey, we’re good, come on, let’s go in!”

There were a lot of curious people.

What effect did local or national politics have on your ability to run a business?

It was always particularly difficult before an election.

In the lead-up to an Election Day, we’d probably get twenty phone calls from theater managers saying that our movies got busted. Then the day after Election Day, we’d get back seventeen of the twenty prints.

In one particular town, before an election, the sheriff would prepare labels for film canisters, such as a ‘Deep Throat’ or Devil in Miss Jones (1973). Then he’d come to our theater – accompanied by photographers from local newspapers – and he’d stick these labels onto empty film cans. The labels had no connection to what was playing in the theaters that day. Then he’d walk out of the theater carrying these cans and get his picture taken, so that everyone though he’d just busted us – and then he’d give us the cans back.

Another reason that caused us to get busted was if a politician was in trouble for something he’d done. In those situations, he would fall back on the issue of pornography. I remember we had a theater in Newark – one of the worst places on this earth – and all of a sudden, one day a local politician got on the soap box and demanded closure of an adult theater which no one could care less about. A few days later, he got arrested for co-mingling his insurance funds in his insurance business.

We were always being busted. It was just a way of life.

We had a theater in Newark and the moral squad would come in every week – a man and a woman – and watch the movie, and then file a detailed report. And so, every so often we’d get busted for obscenity for something in their reports.

What must have made it even more frustrating was that there was a lot of hypocrisy at the time from people in power.

Tell me about it. So many times, the politicians who were prosecuting you… ended in some scandal of their own.

One of the famous political advertising campaigns for a guy called Bill Connors went something like this:

“Hey Tony, lets open up an adult theater in Nassau County.”

And the other guy says “No. Bill Connor’s there. He’s incorruptible. He’ll put us in jail”.

Well… Bill Connors was subsequently arrested and put in jail for cheating on his expenses. That was typical.

Then there was a prosecutor in San Jose, California who kept taking our prints. Now, the law was clear: once the government took one of your prints, they couldn’t take an identical second one because they had all the evidence they needed to try you on a case.

So this prosecutor came along and declared, “I’ll take 50 prints in a row until I put the pornographers out of business. That’s my job.”

A few weeks later, someone noticed an official car up on a lover’s lane and they found the prosecutor there, naked with two 16 year old boys.

What could you do to fight back?

One of our problems was that we never defended ourselves properly. There was no real spokesman for us, nobody who was standing up and speaking for the pornography business.

George Bernard Shaw had been busted in New York City on a censorship charge many years before and he went to jail. He said, “Assassination is the finest form of censorship.” Then there was Benjamin Franklin who said, “Those who give up essential liberty for temporary freedom deserves neither freedom or liberty.” These were good quotes from a lot of bright people.

But we should have done a better job of fighting back because we were just pawns in the game.

What do you think was motivating the authorities to go after adult films? Was it all about religion and morality?

Much of it was motivated by what they thought it did to their property values.

The irony was that in town after town, place after place, wherever there was an adult theater, within ten years, there would be a great deal of improvement in that area – because economically, you never saw an adult theater in either a impoverished or downwardly moving area. You didn’t have any in Harlem, you didn’t have any in Bedford-Stuy, or in Watts, and that’s because the people that lived there didn’t have money go to those theaters, and nobody was visiting their areas looking for XXX theaters.

So the result was, you only would put an adult theater in an upwardly mobile place and the landlord would only rent to an adult business in an upwardly mobile place for two reasons: 1. adult enterprises would take a short term lease which most businesses wouldn’t, and 2. the landlord could get a very high rent from adult film businesses which a business taking a short term lease wouldn’t take.

You can spot this perfectly in Manhattan: 6th Avenue had adult theaters until the Rockefeller Center complex expanded, then they moved to 7th and 8th Avenues. Then they moved over to the east side of Manhattan, until there was no more need for it because home video put pornography back in the home.

*

6. ‘Distortions of Sexuality’ (1972) – and the Birth of Distribpix 2.0

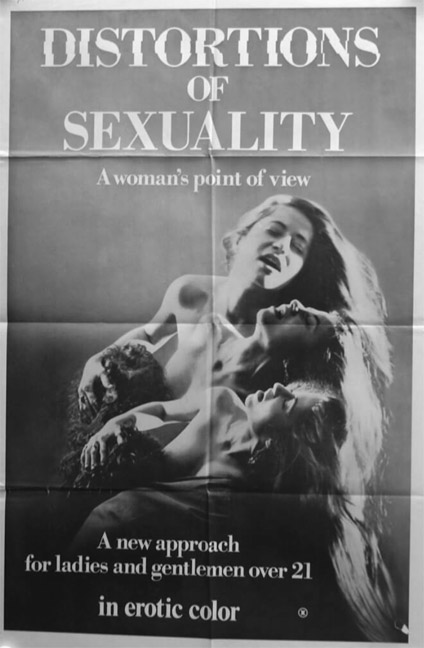

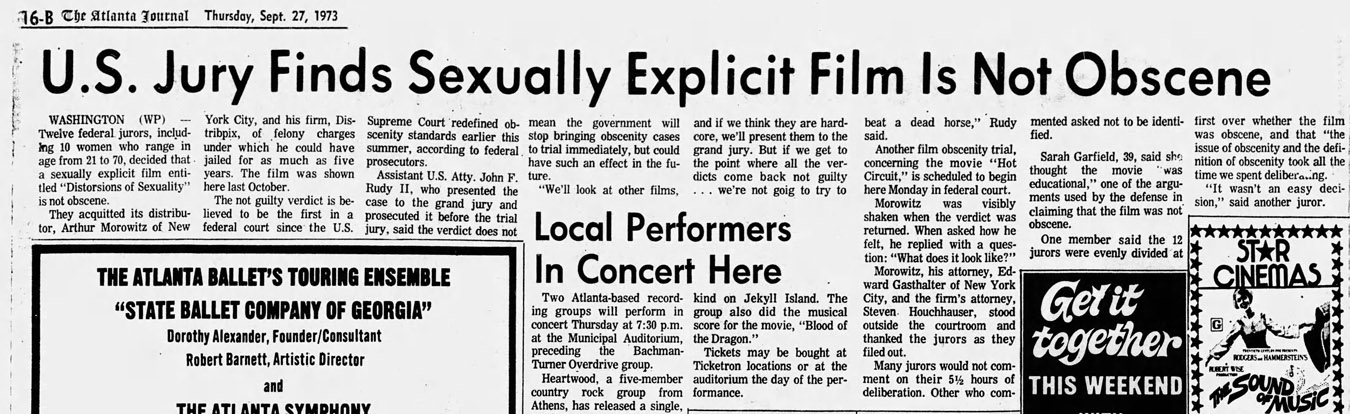

You were involved in a landmark court case relating to a film you distributed called Distortions of Sexuality. What do you remember about that?

That was one of the biggest cases we endured. It was the first case to go to federal trial after the Miller decision in Washington.

It was about a film called ‘Distortions of Sexuality’ – made by a gay director, Gary Kahn. I knew Gary because he had come out of the Lenny Kirtman factory. He’d started out as an unpaid assistant to learn the basics, and then he made a few films which we distributed. Gary was a nice kid but sensitive and unsuited to this business.

The film in question was a nothing film. Nothing good – or bad – about it. But it was busted at a critical time to test the legal waters. And I was in the firing line. The case was high stakes for me as I faced a five-year jail sentence. It was an early test of the new principles that the Miller case had established, and no one had any idea which way it was going to go.

We won because the jury declared it not obscene. That was a big victory because having a film declared non-obscene in a federal district made it fair game for the rest of the country. But the stress took its toll on Gary. I don’t think he made any other films, and I heard he became a sculptor after that and later died of AIDS.

From ‘Jury Clears Film of Obscenity Charge,’ The Honolulu Advertiser, September 22nd, 1973

Twelve Federal jurors, including ten women who ranged in age from 21 to 70, decided yesterday that a sexually explicit film entitled ‘Distortions if Sexuality’ is not obscene. They acquitted its distributor, Arthur Morowitz of New York City, and his firm, Distribpix, of felony charges.

Morowitz was visibly shaken when the verdict was returned yesterday. When asked how he felt, he replied, “What does it look like?”

Morowitz and his attorney stood outside the courtroom and thanked each juror as they filed out.

What were the consequences of that court decision?

Ironically, it was not good. After that victory, we suffered repercussions: the government was angry that they’d lost this case, and they told us they were going to get us, one way or another. They sent the FBI and the IRS to harass us. We just continued our business, but it was difficult.

I had arguments with my Distribpix partner, Howie, and our lawyers, and eventually they made a decision to give up film production and distribution, and instead concentrate on the theatrical side. I was against this and I fought them. I thought it was the wrong course of action. To this day, I still think that we made the wrong decision.

What did you do next?

We gave away all the films that were not ours – and they were mothballed… and we expanded and went from having about six theaters to having twenty.

What do you remember about the theaters you acquired?

There were all types. As I mentioned we had the Sweetheart chain of movie theaters, which included the World, the East World, the Harem, the Orleans, and the Circus. We had gay movie houses too. For example, in 1975 we bought the First Avenue Screening Room at First Avenue and 61st Street, which we turned into a gay theater.

I still see John Amero – who directed a number of adult films, and who worked in your theaters during this time.

He’s still around? He and his brother Lem were great guys. I liked them both. John worked for us for many years as a theater manager.

In the mid 1970s, you returned to film production – what was behind that decision?

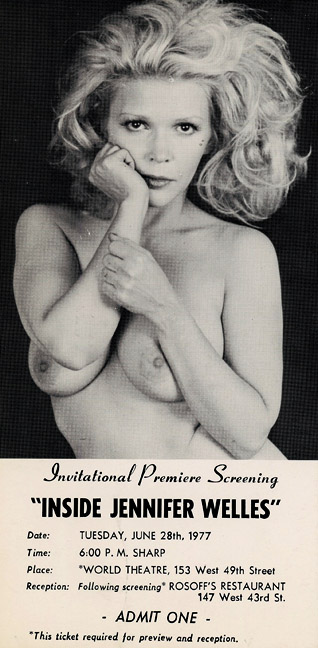

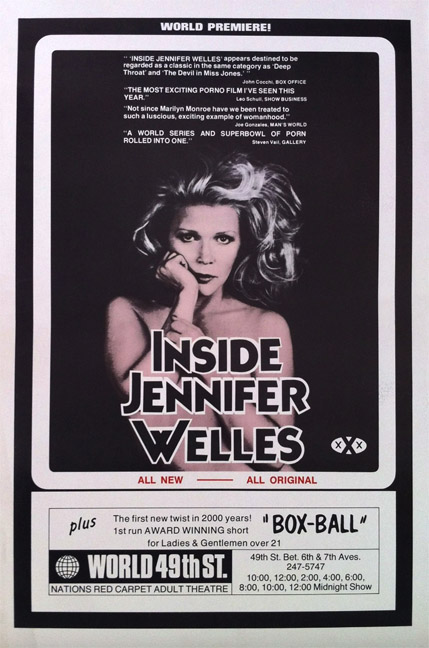

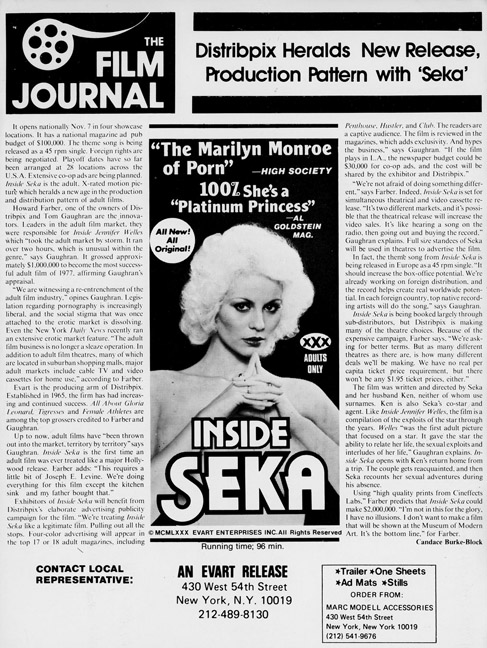

About three or four years later, we went back and made a film called Inside Jennifer Welles (1977).

We got Joe Sarno behind the camera, and he directed it despite his reservations about doing hardcore. We hid his name from the credits, if I remember correctly – and pretended that it was directed by Jennifer herself. As always Joe did a good job. He was much better than nearly all the other directors in the business that time.

Can you tell me about the decision to make ‘Inside Jennifer Welles’?

‘Inside Jennifer Welles’ was our ‘Deep Throat: it put us on the map and established us as one of, if not the, leading company at the time.

Making a film around single star – and an aging one – was an unusual and unprecedented move, but ultimately a very successful one.

What was the thinking behind that?

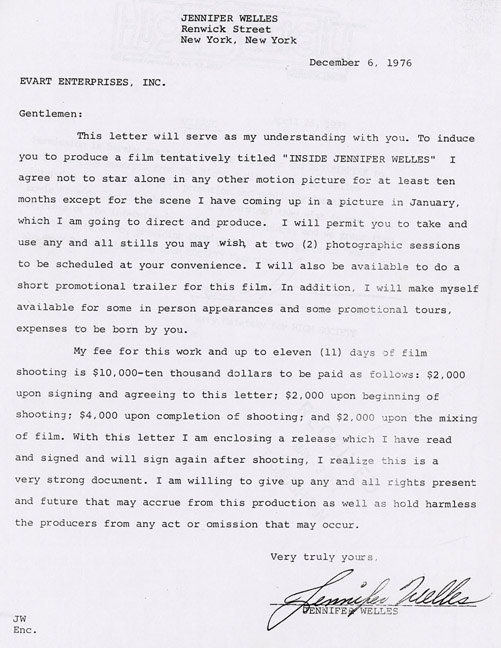

The idea came from Jennifer herself. She’d met a rich fan, and he’d asked her to marry him and retire from the business. She wanted money in the bank in case things didnt work out for her, before she gave up her income stream. It was as simple as that.

How much did she ask for?

She asked for $20,000 to appear in the film. That was out of the question. Most of our films cost around $10,000 – $20,000. But I was interested in the idea. I liked her, and I knew that she was hugely popular – so it would be easy to sell.

We settled on a fee of $10,000 – and exclusivity too. This was the first time a star had that kind of contract.

What was the nature of her exclusivity?

She agreed not to make any other films for 10 months after ours was released. In reality, she did some publicity for us, and then retired and disappeared off the face of the earth.

Wasn’t it a risk having an entire film based around one actress?

At first, everyone said, “Are you crazy using one woman in a porno?” And, “You’re nuts using an old broad like Jennifer Welles.” But the fact was that we knew with certainty that our audience was not relating to the young stars in the same way as some of the older performers. Perhaps that was because the audience was older than her so she was still young compared to the audience.

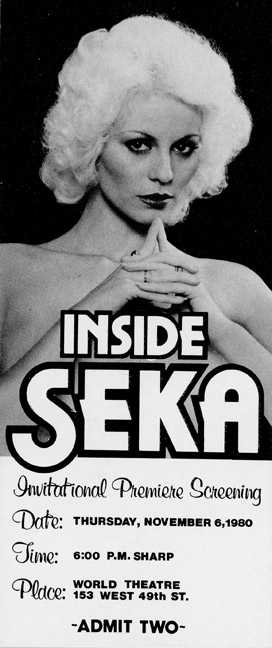

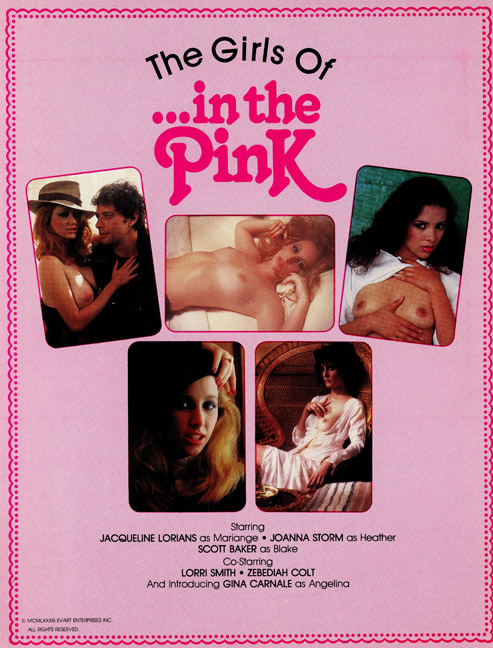

We proved that a star didn’t have to be 20 years old – and went on to make similar films with Gloria Leonard, Seka, Angel Cash, and Annie Sprinkle.

I think it’s the same situation nowadays. People like women who are older than 20… but nobody’s giving these older actresses a break – which I think is ridiculous. If I see one more airbrushed photo of a young star… I find them deeply uninteresting.

Which were the most successful of the star vehicles?

Well, the Jennifer Welles movie broke the doors down for us. After that, the Seka movie did particularly well, but that was because Seka was the number one star at the time.

These star vehicles were much more costly than the films you’d made earlier in the decade.

Yes. They were six-figure motion pictures. Nobody was doing that. And they were big hits because of the way we marketed them, and we made still a good profit from them. And then they sold well on home video, then DVD, and they’re still selling today – so I think our approach was vindicated.

That continued into the 1980s with films like …in the Pink (1983): we ended up spending more than most. Certainly more than anyone on the east coast.

You were also one of the first companies to have big, showy premieres for your films. What were the reasons for doing that?

We didn’t want to be the kind of adult company that stayed in the shadows. We felt we had nothing to be ashamed of. We wanted to behave in the same way as Hollywood film companies – which meant we made full page announcements in magazines, advertised heavily, and had red-carpet premieres for our films.

It was our way of saying that we were proud of what we were doing, and we weren’t going to disappear.

Ticket for ‘Inside Seka’ premiere

Ticket for ‘Inside Seka’ premiere

You were a force on the east coast: how did you view the big companies on the west coast?

There was always a rivalry between the east and west. We felt our films were overlooked at the AFAAs (Adult Film Association of America) for example. The first awards we got were for ‘Inside Jennifer Awards.’

They had a huge advantage: Hollywood was on their doorstep, which meant they had an inexhaustible supply of unemployed filmmakers on their doorstep who were looking for opportunities.

The rivalry was usually friendly though.

So by the late 70s, you were big-budget producers, successful distributors of other people’s films, and had a chain of theaters which you operated?

We were vertically and horizontally integrated.

The vertical came from the fact that we were exhibitors, we were distributors, and we were producers. The horizontal was because we did all those things in multiple locations simultaneously. This meant that on any given issue, I saw everybody’s perspective at the same time: I was the producer, I was the theater owner, and I sold the films. That catbird seat was very interesting, I got to see everything.

By this time, I had split from Howie, and I was the sole owner of the business.

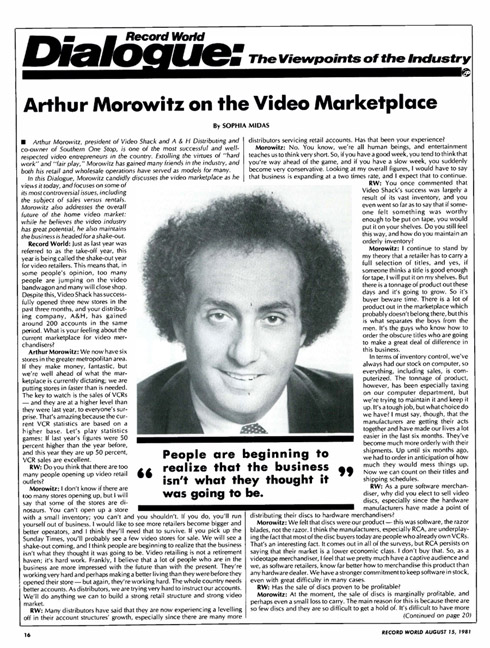

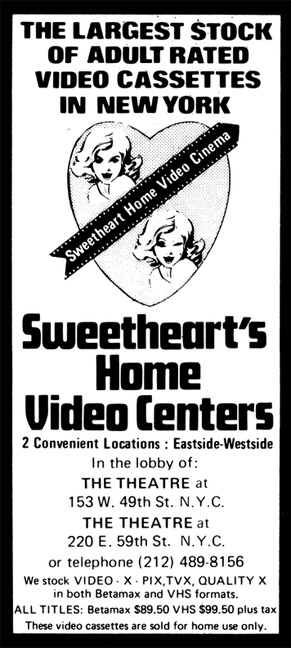

How did you extend that business model when video exploded in the 1980s?

I knew that videos would be a big hit for adult film because it allowed you to take the experience into the privacy of your home. So I began selling our films on cassette in the lobby our theaters.

In those days, they sold for $99.50 and there were lots of people who wanted to pay that amount! It was so popular that I opened a video store next to the theater at 49th and Broadway called Video Shack. That was 1979. At first, we sold about 400 to 450 titles, and 75% of those were adult films. But within a year we were selling over 2,000 different tapes – and most of them were Hollywood movies. We were the biggest tape store in the city.

It did so well that it became a chain across New York.

And then we started the Video-X-Pix line in 1983, and some of the Redlight things…

Looking back, what were the best things you remember about running Distribpix?

I know I’m supposed to say “nudity!” but it really wasn’t. You got over that pretty quickly.

The best part of it was being independent. Believe it or not, most of the people we dealt with were bright, hardworking, and they were gutsy and fun. We had a lot of laughs. We did a lot of serious things, but we didn’t necessarily do them seriously.

I think even a lot of the law enforcement officials had fun, even though they were arresting you. I mean, having gone through 10,000 homicide photos, what’s one guy in a porno film going to do to you?

How do you look back on your career?

I loved it. I have no regrets. It was fun. My only criticism was that it was only ever a small business: if it had been a big business, Sears would’ve been in it. Sure, it’s a bigger business today than it was 25, 35, 40 years ago but it was a small business back then. And it’s still a relatively small business today.

To me, it was an economic business just like any other. I never was ashamed of it, and I was proud that we did some good things along the way.

I’ve been married to the same woman for over 40 years, and she was with me from the beginning of business. It was a good ride. I’ve been lucky.

*

Arthur, with Vanessa del Rio in Tigresses (1979)

Arthur, with Vanessa del Rio in Tigresses (1979)

*

I was aware that Arthur Morowitz had passed in September, but couldn’t find an obituary that reflected his immense impact on the adult film industry. It seems that like many other giants of the business, most “historians” never took the time or trouble to actually document his life story. Since thanks to The Rialto Report for this fascinating, factual history lesson. Without it, how much would actually be lost to history?

Really informative read, thanks Arthur, and my condolences to his family. A true loss.

Was anyone as influential as Morowitz in as many fields over so many years?

A titan, and sad news.

R.I.P.

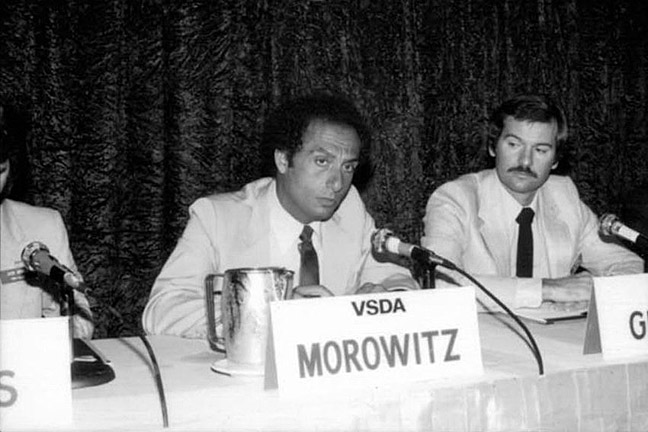

My prayers to the Morowitz family. I met Arthur once at a VSDA convention. He was soft-spoken but confident and clearly intelligent beyond all the others in the room.

I would love to hear more about his life.

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work

This is fantastic and eye-opening. The Rialto Report always knows where to look, what to ask, and how to present their work. Excellent!

A great reading and very informative… Thanx…

Amazing journey through the Sexual Revolution where this guy had a unique view. I loved hearing about how the women were interested in these films back then – more than their boyfriends or husbands!

Video Shack was a great store and groundbreaking in the home entertainment biz! They were legit and were the first to have any Hollywood movie on cassette before VCR’s became mainstream. Got to meet “Elvira” Cassandra Peterson the first time, when her TV show was released on cassette and she she did a promotional appearance. Another great report guys, thanks!

Thank you for this. I had no idea and it’s a shame his passing has seemingly been so overlooked. I remember the Joe Sarno documentary and his widow Peggy being thrilled with the size of his New York Times obituary. No such luck here, because even if he hadn’t been mentioned for Distribpix, Video Shack was a very big deal in the early 80’s, a staple of every NYC visit.

My sincere condolences to Steven, who I corresponded with via email when he was releasing the Henry Paris restorations and met at a “Roommates” screening, and the entire Morowitz family.

Would be interesting to get someone’s take on how films got distributed through the South, particularly at drive-ins. Often times they had to splice out some of the naught bits which didn’t make the distributors too happy when they got their prints back and sent them back to a grindhouse. And the “arbitrarily-drawn lines around the country,” aspect seems ripe for abuse as it’s somewhat similar to how pro wrestling dealt with territory boundaries. I know when drive-ins started losing the higher budgeted movies the owners would sometimes band together and finance movies themselves, for example Chattanooga Choi-Choo. Fascinating article! Thanks.

Fascinating to read such an analytical “businessman” take on the industry. Almost like hearing a veteran real estate developer, restaurateur, or retail chain founder discussing their career/industry. Kudos for exploring the business side of adult films in a straightforward fashion with Mr. Morowitz.

This is why I love The Rialto Report so much – one week there is a deeply personal, empathetic, and emotional article about someone (recent examples include Frankie Leigh and Jake Teague)…….. and then a serious, intellectual, history lesson, such as this interview Distribpix head honcho, Arthur Morowitz. Excellent.

I only wish that the remaining film companies had a similar quality threshold for their extras (paging Something Weird Video or Video-X-Pix or Vinegar Syndrome). Some of the recent “essays” by bloggers including with Blu-ray or DVD releases are breathtakingly amateurish.

This site restores my confidence in what an intelligent and original approach can yield. For that, thank you.

Forget ‘Barbie’, the world needs a RR movie!

Genius is an over-used word but the term covers Arthur’s talent in production, distribution and exhibition. He had savvy, foresight and intellect. The strength of an interview is the desire to read or hear more. The Rialto Report correspondents understand this.

the life of some of these people in ny would be a great movie for sure. Great stuff rr

More greatness from you guys at The Rialto report, I LOVE every single article on this amazing site, bravo!