Lucky Kargo and Kemal Horulu.

Two unknown men, two unusual names, and two unique lives that intersected in the 1960s and 1970s.

What brought together a wealthy Muslim, ex-Olympic athlete, and Academy-award nominee, with a juvenile gangster, prize-winning dancer, gigolo, bodybuilder, adulterer, gambler, stuntman, and sex film actor? And what role did they play together in the early adult film industry?

Their story is told for the first time.

Thanks to Lucky Kargo, Kenneth Schwartz, Isabel Horulu, Dale Fuller, and others interviewed for this article.

———————————————————————————–

Lucky Kargo, 2005

In the rose-tinted world of Lucky Kargo, truth was a relative concept. The only problem was that nothing he said was untruthful either. He was the nationally famous, glittering star of his own life story, the matinee idol of his dreams.

When I pointed out to him that his stories sounded barely credible, he smirked with sheepish charisma, his unnaturally white veneers lighting up the dark bar.

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” he shrugged happily. Lucky loved quotations. Especially ones from movies. Old-time classic Hollywood movies.

“That’s from John Ford’s ‘The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance?’” I asked.

“I don’t give a damn what you say about me, just as long as you spell my name right,” came the smiling retort.

“And that’s P. T. Barnum. Wasn’t he a smooth-talking conman known for exaggerating and self-promotion?” I offered.

Lucky laughed and leant back in the plastic-padded booth: “My life has been more interesting than anyone you’ve ever met. That’s why you’re here today, right?”

Lucky Kargo, actor, dancer, gigolo, bodybuilder, adulterer, gambler, stuntman, sex film performer, and happy dreamer, had a point.

We were sat in Hollywood talking about his unlikely life in show business. Not Hollywood, California, though – rather Hollywood, South Florida. And not the Beverley Hills Hilton, but a dive bar in Lucky’s local ballroom next to his apartment building that resembled a rusty toaster.

Lucky was 70, still handsome, loose-limbed, and tanned browner than a mahogany dresser. His grey suit hung loosely on his lean frame, his white shoes in perpetual motion dancing under the table. He’d been living in this low rent strip mall suburb north of Miami for several years, earning money as a dance partner for elderly snowbird yentas escaping the wintry northeast. The women wanted nothing more than an arm around their waist and an afternoon waltz or jitterbug while their aging husbands napped in overly air-conditioned condos. In truth, they sometimes wanted a lot more, but somehow the aging lothario had his limits: “Strictly no hanky panky, darling,” he would whisper softly in their ears, as seductively as a declaration of love.

It was a hand-to-mouth existence but a comfortable-enough one: Lucky earned $4 for a dance, his flirtatious compliments were free, and the starstruck dames couldn’t get enough of his snake hips, handsome smile, and seductive patter.

It was easy work for Lucky, combining the North Star passions that had always dominated his life: his love for women of all shapes and sizes, and his ability to dance any style that had ever been invented. But perhaps his greatest skill was that he made every woman he ever met believe he was having the time of his life with her. Either that, or he really did love every single one.

“It’s never too late to be who you want to be,” sighed Lucky.

Or perhaps that was F. Scott Fitzgerald. After a while in Lucky’s company, it was hard to tell what was real and what was fiction.

*

Lucky, the Dancer

Lucky was a New Yorker. Never mind that he’d spent most decades of his life living out of a suitcase in Las Vegas and in dance halls across California, trying to convince talent agents that he was a uniquely unlikely combination of Gene Kelly and Humphry Bogart. He’d left New York many years ago, but he was still a quick-witted, street-smart, wheeler-dealing confidence artist at heart.

Lucky was born Frederick Kargoll in 1925 in Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital. Eighteen pounds at birth, if you believe his hype. His father was a construction worker, and his mother cleaned the Paramount Theater between movies. The Kargoll family lived in a closet-sized single-room apartment in Hell’s Kitchen before upgrading to a one-bedroom, cold-water, walk-up at 1141 Elder Avenue in the Bronx. Mostly though, Freddie lived in the back of the Paramount, left to stare at the enormous screen for hours while his mom scrubbed the floors. His babysitters were the ticket-buying movie fans at the theater – an upbringing he claimed led to his love of movies.

His parents neglected him, and so Freddie became restless, bored, and before long, a gangster. Not a goombah, gun-toting, wise-guy gangster – he lacked the connections and ethnicity – but a gangster nonetheless, and a young one at that.

“I was a bad kid,” he admitted. “My first racket started when I was ten: the corner bodega guy, who sold fresh produce, milk, cigarettes, had his store windows broken. I told him I’d make sure it didn’t happen again: it would only cost him $5 a week. He didn’t take me seriously. Then his windows got broken another time. And then again. Eventually the bodega guy agreed to pay me for protection. Except my price had gone up. Now it was $10 if he wanted to keep his shop safe. That was a lot of money in the depression, but he paid me anyway – and guess what? The vandalism stopped overnight. Of course, it had been me breaking the windows all along. I rolled another 15 stores across the Bronx doing the same. It was a regular income.

“I didn’t stop there: I wouldn’t think twice about roughing up an old man if I saw a loaded wallet. I don’t feel good about it now, but it was a jungle back then. I was a hoodlum and I always had $100 in my pocket.”

Lucky acquired his nickname from his unnaturally poor fortune at the craps table in the gambling halls of Atlantic City. And when he wasn’t being a street thug, he could be found in the dance halls in upper Manhattan where he discovered the second most important passion in his life: dance. (“Everything was secondary to sex. That always came first when I was young,” he grinned.) Soon he built a reputation as one of the best dancers in the city.

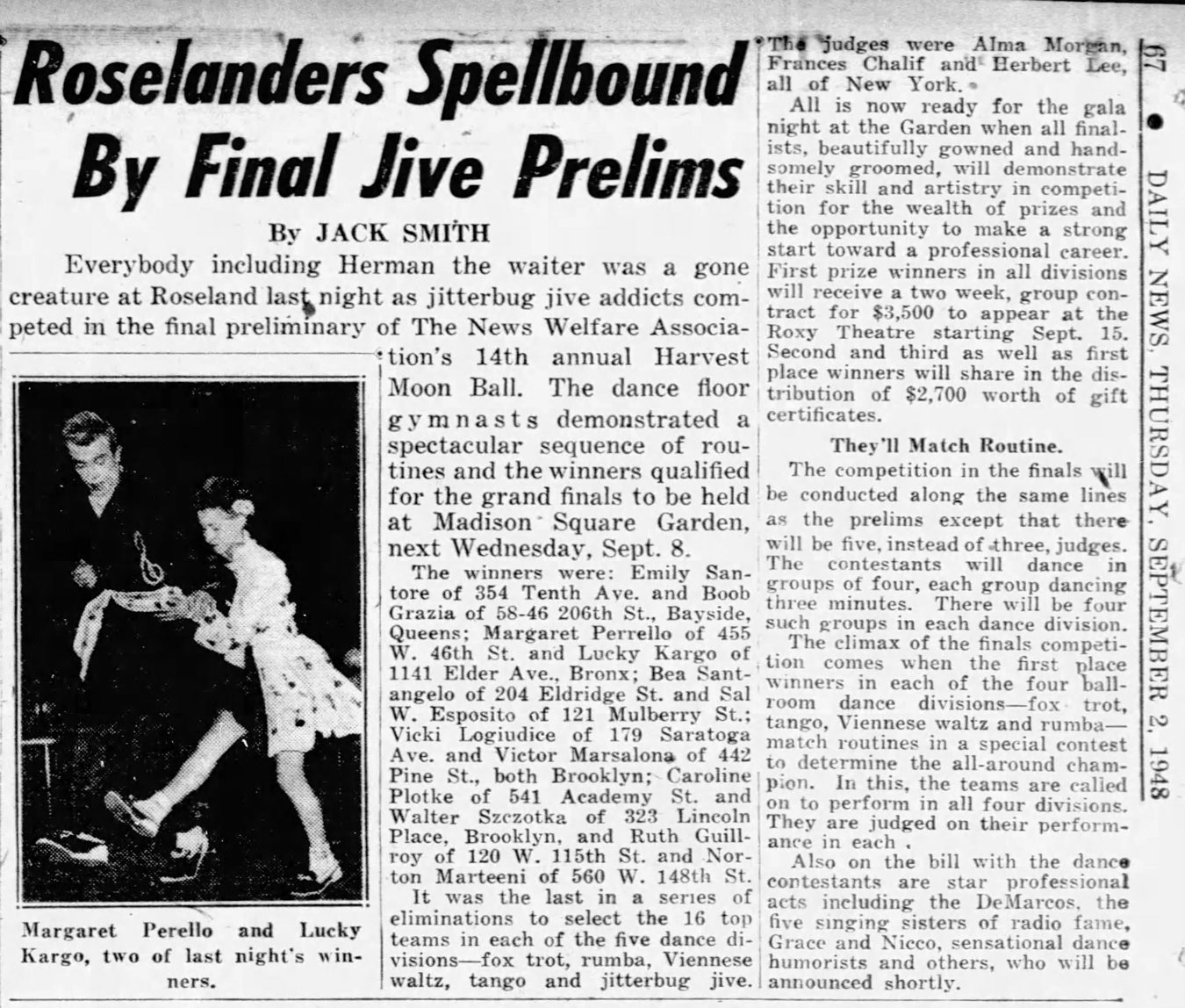

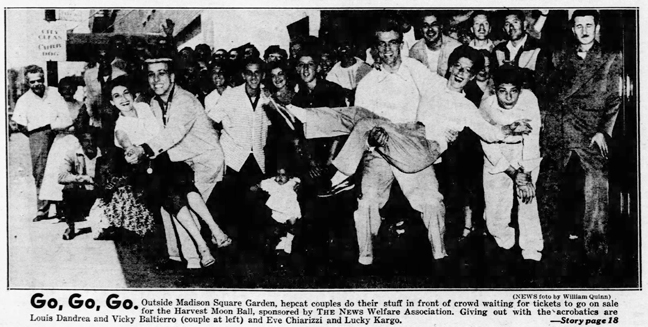

First newspaper mention of Lucky Kargo, September 1948

First newspaper mention of Lucky Kargo, September 1948

‘It came easy to me,” Lucky admitted. “I had a few lessons when I was a kid, but mostly I just watched the old guys. I observed them closely… their steps, their hips, their guile… and my feet did the rest. Pretty soon, there wasn’t a dance I couldn’t do better than anyone else. You name it – foxtrot, rumba, waltz, tango – I was slicker and smoother than an oil spill. I loved it: the music, the moves, the sex. Dance is all about sex. And both were lucrative in those days.”

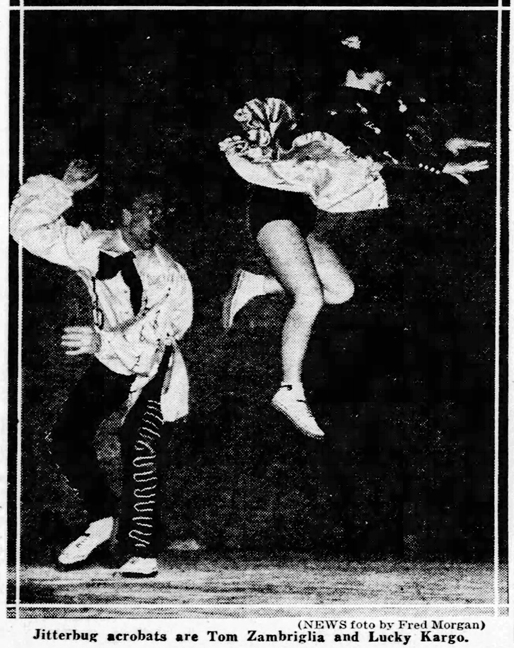

Lucky Kargo, Daily News, September 1949

Lucky Kargo, Daily News, September 1949

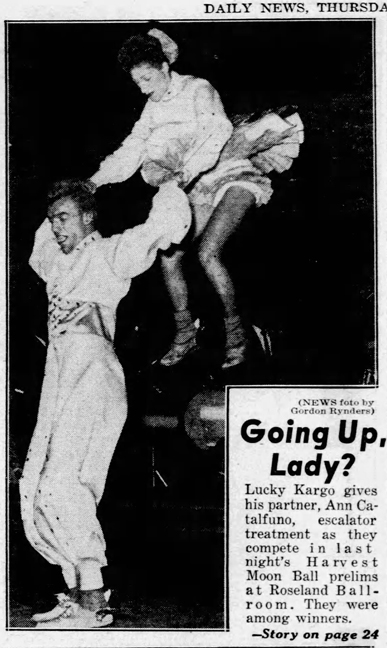

Lucky Kargo, Daily News, September 1951

Lucky Kargo, Daily News, September 1951

In the 1940s and 50s, Lucky took part in regular dance contests across town, such as the prestigious Harvest Moon Ball, and he won most of them. He specialized in acrobatic jiving, an athletic form of jitterbug, consisting of throwing your partner into the air at regular intervals while maintaining a perpetual look of self-satisfied nonchalance. Prizes for each contest ranged from a couple of thousand to $10,000.

In 1948, he qualified for the grand dance final for the first time – an event that took place at Madison Square Garden. With a large sum of money being awarded to the winner, Lucky left nothing to chance: “I found out the names of the judges and made sure I took care of them: a meal or two, some cash in an envelope, even a willing girl from time to time. Whatever worked.”

Lucky Kargo in action at the Garden

Lucky Kargo in action at the Garden

And it did work: Lucky was crowned 1948 Champion of Champions, the city’s best dancer. It was the first of several similar triumphs in the years to come.

I asked him how his life changed after his first big success.

“You should know I was Lucky Bang Bang before I was Lucky Kargo. That was on account of my sexual conquests,” he admits with nostalgia. “After I won at the Garden, I slept in a different bed every night. I got to know a lot of women. And I saved a heck of a lot of money on rent.”

Lucky, in the Daily News, August 1953

Lucky, in the Daily News, August 1953

*

Kemal, the Athlete

At the same time Lucky was triumphing on the hardwood dance floors of Madison Square Garden and shtupping his way across the pink bedrooms of New York, another playboy was preparing for athletic competition.

In 1948, Kemal Horulu landed in London with the rest of the Turkish track and field team to take part in the Summer Olympics. He was the most prolific member of the entire team, there to take part in three events: 400 meters, 400 meters hurdles, and the 4 x 400 meters relay.

The international media swarmed around the young Turkish sprint star, drawn to his natural charisma and dark good looks as much as his medal hopes. (“Tony Curtis was plain in comparison,” remembered his future sister-in-law. “Hands down the best-looking man I’ve ever seen,” concurred a friend.) Kemal was unfazed by the attention. He was just looking for a good time.

Kemal was born in 1926 from unlikely stock, a family of wealthy Muslim refugees. His father, Ibrahim, was born in Dagestan, a distant Russian republic situated in the north caucasus of Eurasia along the Caspian Sea, while his mother, Havva, was from Ukraine. Together they established a flourishing jewelry business in Trabzon, a city on the Black Sea coast of northeastern Turkey, located on the historical Silk Road.

Havva was devoted to her two sons, Hussein and Kemal, and insisted the family move to the more cosmopolitan city of Ankara, where the boys could have university educations from the country’s leading scholastic establishment. So the family settled in Ulus, the heart of old Ankara, where Ibrahim established the biggest jewelry store in the city.

Hussein and Kemal were both attractive and charming, but as characters, they were like oil and water: Hussein, four years older, was sober, serious, straight, destined for a conservative career as an insurance lawyer. Kemal was the wild child, the prodigal son or the black sheep depending on your perspective. Havva loved them both but doted particularly on Kemal, curating a room in the family home to house the athletic medals, cups, and certificates that he started winning. The boys were both successful but clashed frequently, and the bad blood between them lasted all their lives.

Like Lucky Kargo, Kemal was a dreamer who fantasized about Hollywood and the movies. Turkey, with its minor-league, fledgling film business, failed to satisfy him. So he trained hard as an athlete, convinced that traveling to international competitions would give him more opportunities to find the excitement he craved. It worked. After the 1948 Olympics in London (Kemal was eliminated in the heats of each of his events), he stayed in the city to sample the permissive nightclubs and the willing women. Four years later, in 1952, he represented Turkey again at the Olympics, this time in Helsinki. By now his athletics prowess had made him a celebrity in Turkey: cabinet ministers and television stars treated him like royalty, and women fanned themselves energetically in his presence.

But Kemal’s athletic success also papered over the fact that he had no career plan. He’d completed his compulsory army service, and drove a taxi cab around Ankara, but his parents fretted about his lack of direction. Kemal wasn’t worried about the long term: he had his sights set on his first trip to America. In late 1952, it was announced that Kemal, as part of a small group of elite runners, had been invited by the U.S. Amateur Athletic Union to take part in the indoor U.S. winter track season.

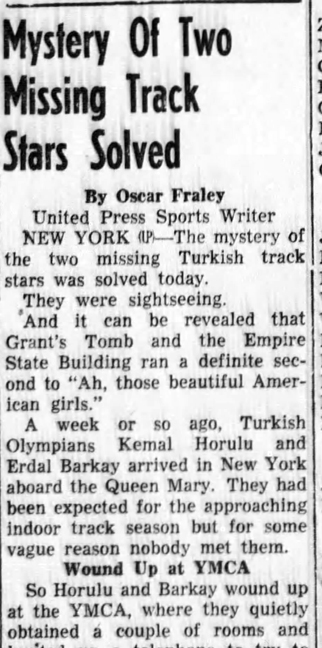

Kemal traveled to New York on the Queen Mary, accompanied by a fellow Turkish athlete, and both promptly disappeared. For a week, the case of the two missing Turkish men became an international mystery. Articles appeared in the newspapers, TV news programs covered the story, diplomats were summoned, detectives were alerted, and cops tried to find what had happened to them after they disembarked in New York.

A week later Kemal surfaced, giving interviews to the media, claiming he’d been staying at the New York Y.M.C.A. and spending the days sightseeing, oblivious to the manhunt taking place: “We walked around and looked at all the tall buildings,” Kemal was quoted, “and we watched these oh so beautiful American girls. It was nice – and I wasn’t in any hurry to begin training.”

The newspapers described Kemal as a “handsome young man” and admitted they were “spellbound by Horulu’s travel talk.”

Kemal took part in the athletic events as planned – but by now, his head was turned. He still didn’t know what he would end up doing but he knew that, going forward, he was going to do it in America.

*

Lucky, the Actor

Lucky had the New York dance scene sewn up: regular newspaper articles covered his exploits in the ballrooms, girlfriends satisfied his libido, and he had enough money to eat at Shun Lee Palace every Saturday night. But Lucky was growing up, settling down, and he wanted more. He wanted a career in acting.

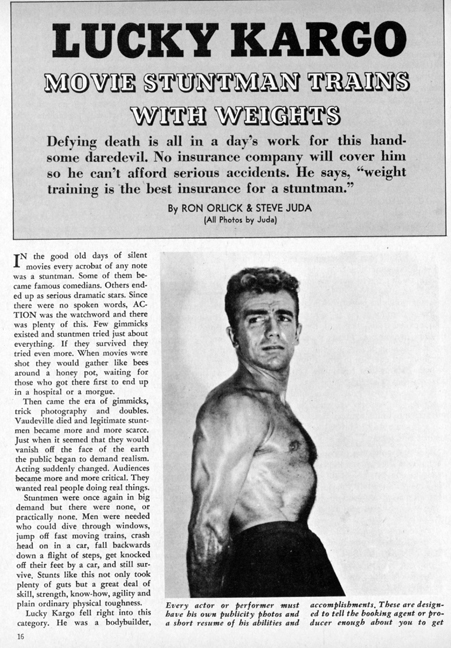

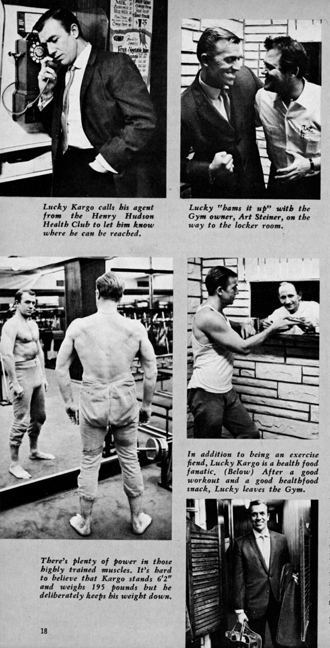

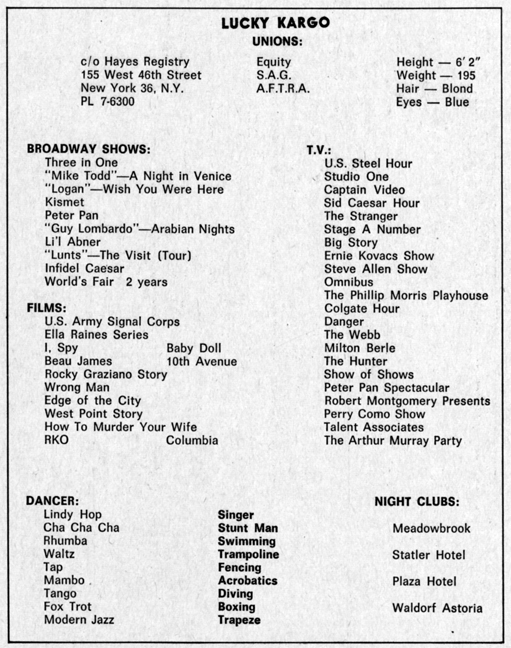

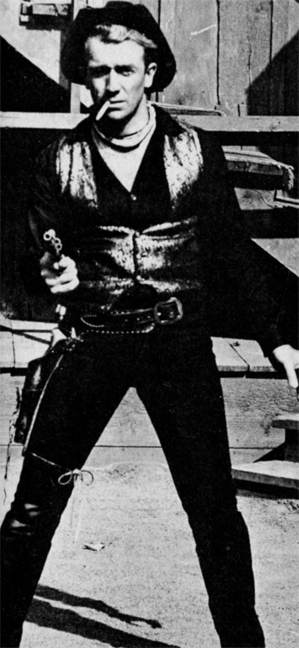

He took acting classes and auditioned for every theater play he could find. It was slim pickings: he got a few minor jobs – a replacement dancer in Kismet at the Ziegfeld in 1953, a stand-in for a pirate in the Winter Garden Theatre’s off-Broadway production of Peter Pan in 1954, and a role in the chorus of Li’l Abner in 1956 – but it failed to meet the expectations of his dreams. So he turned his attention towards film: he’d always taken care of his body, working out at the Henry Hudson Health Club on 57th St, developing an impressive bodybuilder physique. He was also a decent boxer and martial artist, so he started to market himself as a stunt man.

“Over the course of the 1950s, I was in 50 or 60 films – usually fight scenes, and never credited,” Lucky admitted ruefully. “I became the first guy they called when they needed a hard body who’d stand in for the lead. I was Paul Newman’s double in ‘Somebody Up There Likes Me’ (1956), I was in ‘Baby Doll’ (1956), and also Henry Fonda’s stand-in for Hitchcock’s ‘The Wrong Man’ (1956). It was good, I guess: I got to see how films were made, I picked up some money, some contacts, and usually a broad. But I never got a single credit.”

Lucky still took acting roles whenever he could find them, like small parts in New York-based TV shows such as ‘Big Story’, ‘Danger’, ‘Janet Dean’, and he did a ‘Bonanza’ episode too. In 1959-60, he went on the road with Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt’s national tour of ‘The Visit’, though his involvement was more notable for his romantic entanglements than his acting: one time, Fontanne and Lunt caught him jumping from a second-story window to escape a jealous husband.

“That wasn’t uncommon. I was caught two times jumping out of windows, three times running out of an apartment, and once I hid underneath a car because a husband was looking around,” admitted Lucky.

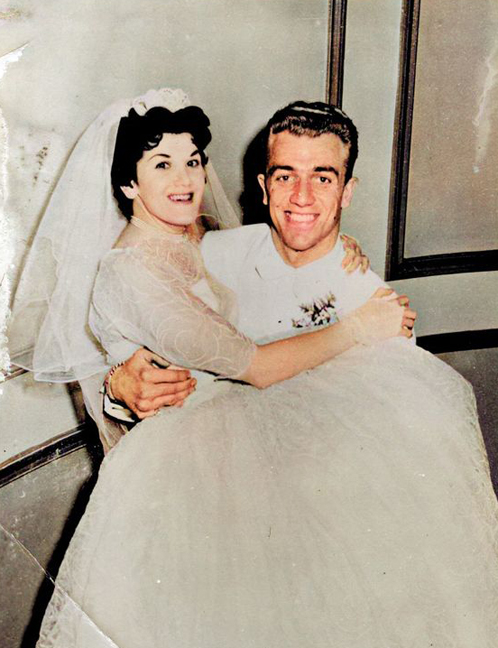

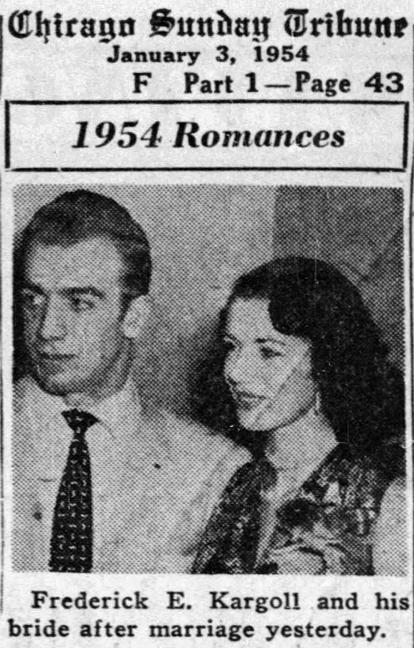

Lucky seemed destined to be ill-fated in love. His first wife tried to commit suicide when she discovered she was pregnant and he didn’t want her to have an abortion. He nursed her back to health, then left. His second wife asked for power of attorney, then divorced him, and made $46,000 when she sold their house.

Lucky, and his not-so-lucky second bride

Lucky, and his not-so-lucky second bride

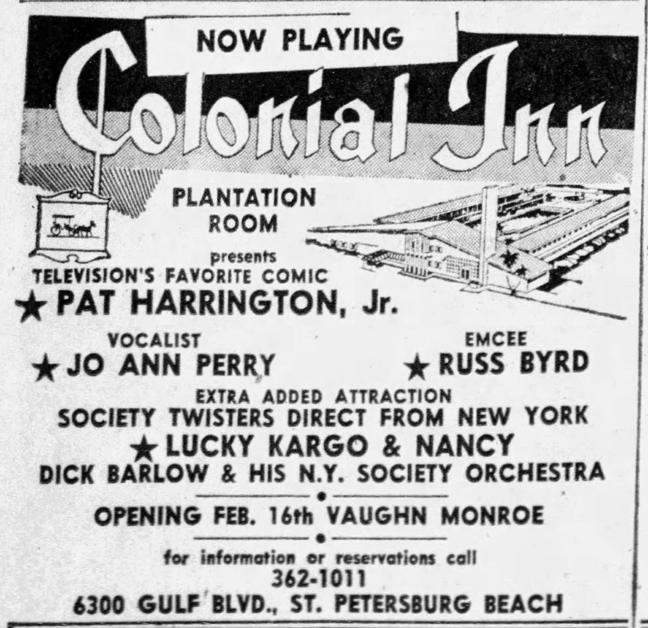

Acting jobs were hit and miss, so Lucky danced on cruise ships. In 1957, he formed ‘The Lucky Kargos’ (“Sensational Dance Artists of Stage, Shows, & TV”) whose gigs included supporting jazz great John Coltrane at the ‘First Jazz Colossal of 1958.’ When the Twist dance phenomenon hit, Lucky cashed in and formed a dance routine troupe together with an orchestra that toured the east coast supper clubs: ‘Society Twisters Direct from New York – ‘Lucky Kargo & Nancy’ – with the N.Y. Society Orchestra.’ In 1959, Lucky decided to go relocate to Las Vegas for a year where he worked at the Tropicana.

Lucky at the Tropicana, Las Vegas, July 1959

Lucky at the Tropicana, Las Vegas, July 1959

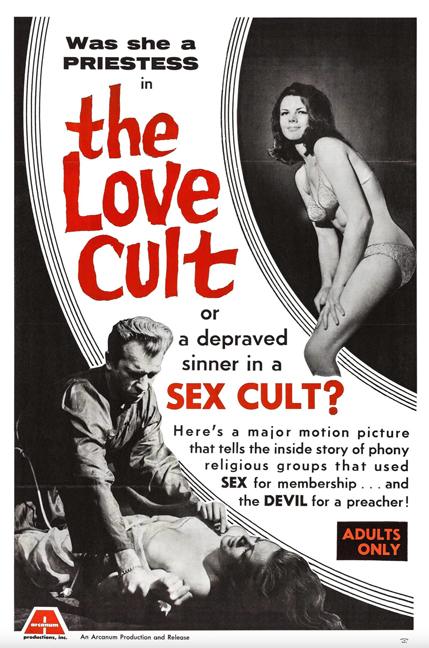

In 1966, now back in New York, Lucky answered an ad for a role as a leading man in movies: “It was just a short paragraph in Variety. Or the Village Voice. I spent part of each day looking through the ads to see what interested me. This one said something like: ‘Good looking lead wanted for independent horror film. Must have a good body – and be willing to show it off. Also willing to act in love scenes.’ I thought, what could be more perfect for me?”

Lucky turned up at the Film Center Building on 630 Ninth Avenue for the audition dressed to impress: “I thought this was my big chance. I was in my early 40s but I still looked great. I knew I wouldn’t have many more chances to get a lead role so I was determined to kill.”

That day, Lucky met veteran sexploitation director, Barry Mahon, and they hit it off instantly: “Barry was a similar age to me, a west coast guy originally, and with an incredible life story. He was a second world war hero, and then was Errol Flynn’s manager, and now was making these low budget, black-and-white indie sex films out of his apartment in New York. I loved the guy. He hired me on the spot and together we made The Love Cult – the first movie where I was the lead.

“The film was a revelation. The crew consisted of Barry and just one other guy who did the lights – and maybe he did the sound too. And we shot it over a single weekend – and it was in the theaters within a few weeks! What’s more, I left the set with the lead actress, Rita (Bennett).”

*

Kemal, the American

In 1954, Kemal Horulu moved to New York.

He loved Turkey, and was especially close to his mother, but he’d set his sights on a career in film and had fallen in love with the Big Apple. The one problem with moving to the U.S. was that his family’s wealth wasn’t available to him – currency exchange controls meant that he couldn’t exchange more than the equivalent of $140 a week, so he needed to find a job to survive. Kemal embraced his inner-American self and chose the most American of jobs, becoming a car salesman for Lincoln Mercury. It was a job he held for several years as he built up his savings.

Kemal had everything going for him: he was good looking, charming, well-educated, and athletic. For a while, he was happy to push his film career pipe dream onto the back-burner while he partied in nightclubs, dated starlets, and spent weekends with friends in the Hamptons.

In the early 1960s, Kemal met his perfect foil, the ultimate wingman, Lucky Kargo, at the Copacabana.

“My best friend, Kemal!” exclaimed Lucky when I mentioned his name. “We were so tight. That man exuded pure class. He was sophisticated, intelligent, and cultured. He was dating a famous opera singer when I met him. We became best friends. I called him the ‘Arab’ because he had a dark complexion and he was amazing looking. He was the only man who could seduce a woman into a bedroom faster than me. We were compadres… partners in crime, in life, and then in film.”

Kemal and Lucky did everything together, gallivanting across the city with an assortment of glamorous women, having the time of their lives. Summers were spent on the beach; winters in the warm midtown bars and clubs of the frozen city.

By 1962, Kemal figured it was time to ignite the next stage of his life. And so with a degree of sadness, he gave up the party life and moved to California where he enrolled in a master’s degree program in cinematography at USC. He graduated with honors, impressing his college tutors with his seriousness and keen eye for lighting.

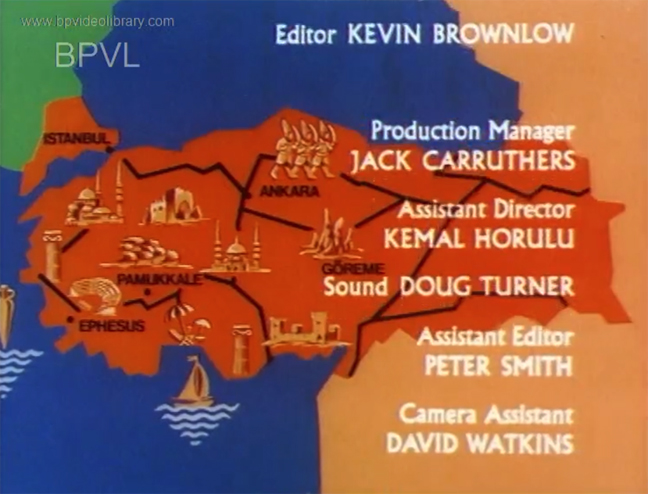

In 1965, Kemal returned to Turkey, inspired by Yilmaz Guney, a Kurdish film director, who had started to attract attention with his depictions of the plight of ordinary working-class people. Kemal wanted to launch his own film production company and so approached his brother, Hussein, by now a successful lawyer, for a loan. Hussein turned him down flat. Kemal had no experience, Hussein said, and it would be foolish to invest in a venture backed by a complete novice. Kemal, stung by the familial rejection, got a role as an assistant director on a film called Turkey the Bridge. The film was a travelogue about the history of Turkey from 200 BC through to the creation of the Turkish State and the modern tourist industry. It was intended to be nothing more than a useful experience on a small scale project, but much to the surprise of all involved, the film was nominated for an Academy Award in 1966 in the short film category.

Title card from ‘Turkey the Bridge’

Title card from ‘Turkey the Bridge’

Buoyed by the unexpected success, Kemal decided he would pursue a film career in the U.S. In 1966, he moved back to New York, where his Oscar nomination earned him a small apartment in International House, a private, non-profit residence on the Upper East Side reserved for academics, research scholars, and select artists. Naturally, he re-connected with Lucky, and talked about his movie-making ambitions.

And so Lucky introduced him to Barry Mahon.

*

Kemal and Lucky, the Filmmakers

Lucky was still taking any acting work that he was offered, which included being Kirk Douglas’ stuntman in ‘A Lovely Way to Die’ (1968), and an extra in ‘Midnight Cowboy’ (1969). In 1967, he got a call from Barry Mahon, who wanted him as the lead in his new film Sex Club International.

Lucky remembered: “The Arab was the assistant director on this new film. Barry had already hired him as a cameraman, but this was the first time he gave Kemal a more senior role. It was great working together, and we had fun doing these movies.

Lucky in ‘Sex Club International’

Lucky in ‘Sex Club International’

“‘Sex Club International’ was a James Bond parody – and I was the secret agent who had to stop a prostitution racket. I told Barry that I had once been called ‘Lucky Bang Bang,’ and Barry loved that. So he called my character ‘Lucky Bang Bang’ and splashed the name over the poster too.

‘Lucky Bang Bang’ on the billboard at The Strand theater

‘Lucky Bang Bang’ on the billboard at The Strand theater

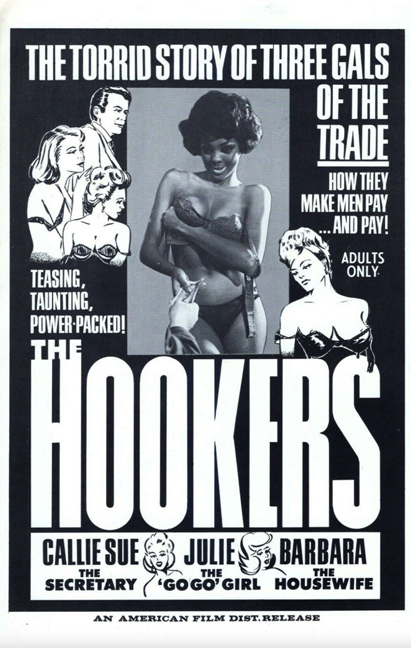

“It was a strange time for me: some weeks I was hanging out with Kirk Douglas and Dustin Hoffman, and then the next week, I was in a film like The Hookers (1967), or rolling in the sack with one of the beautiful Bennett sisters. God, those two girls seemed to be in every Mahon film for years. They weren’t smart or cultured, but boy they were pretty.”

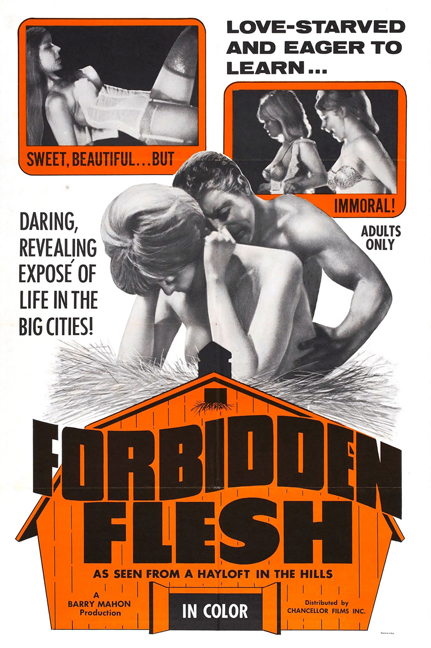

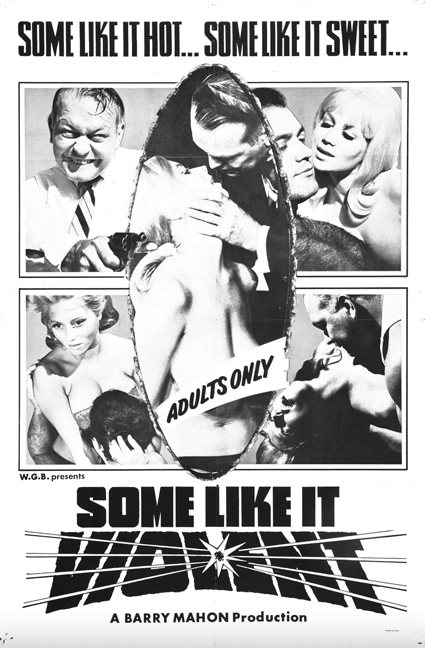

Kemal’s arrangement with Barry Mahon was informal, allowing him to direct films for Barry’s production companies – ranging from the average Forbidden Flesh (1968) to the excellent Some Like It Violent (1968) – or take an anonymous crew role for a quick buck. Lucky helped out on the same films, his role varying from setting up the lights, manning the sound, or operating the camera if required. Lucky was seldom credited for his behind-the-camera work: it was intentional as he preferred to maintain his image of the lead actor rather than a multi-purpose utility crew member.

Despite the obvious sexual content in his films, Barry Mahon made it clear he didn’t want explicit sex – and this became more of a commercial problem as time went by: “Barry liked big hair, big boobs, and big underwear too,” remembered Lucky. “But when other filmmakers started to be more daring, and showing actual sex, Barry got cold feet, and started to withdraw from the sex film business. One day, he told us he wanted a new career making kids movies… can you imagine that?! Talk about a change in direction!”

Eventually Kemal decided to go it alone, and set up his own production company. His first film after the split with Mahon, The All American Honeymoon (1969), was an inauspicious and atypical misfire. Clinging to the idea that he could make a mainstream melodrama, Kemal teamed up with Sidney Antebi, a graduate of the Dramatic Workshop, whose alumni had included Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, and Tennessee Williams. In the late 1960s, Antebi was running Heritage Theater One, a non-profit, educational theater workshop, whose stated aim was to produce every single of the major works of Western drama from the Greeks to Arthur Miller by staging a new play every two weeks. Despite this recklessly ambitious vision, Antebi found time to sell a romantic comedy script to Kemal on the condition that the ensuing film would be produced by his brother, Joseph Antebi. They raised an $80,000 budget and hired a legit union crew, but the result was neither romantic or a comedy, and Kemal decided to return to sex films with renewed conviction and vigor.

Lucky and Kemal became closer: as Lucky remembered, “It was clear the sex film business was going to thrive by being more permissive. And we saw an opportunity for anyone who was willing to take a little more risk. The only problem was that neither of us were natural risk-takers. We wanted to make films, we wanted to make money, but we wanted to stay out of jail too!

“We agreed we’d make a few films together: Kem would direct and I’d put the production together, and we’d keep our names outta the credits completely. It was a fun time: we were best friends and we spent every night at Keneret restaurant on Bleecker Street – a middle eastern restaurant that Kem loved – writing, planning, and organizing the next production.”

As if to emphasize the changing of the guard, Kemal took over Barry Mahon’s former office in the Film Center building.

*

Kemal and Lucky, the Pornographers

At the dawn of the 1970s, films could only show explicit sex if there was a good enough reason. And not just any reason: the reason needed to have socially redeeming value. Which meant one thing: these smutty sex films had to be educational.

So suddenly a glut of pseudo-documentary adult films flooded the screens, hosted by quack psychologists, narrated by haughty academics, explained by dubious doctors – ostensibly presented to help revive sexless marriages. All this so the viewer could see real porn stars having real sex. And real sex then meant mechanical, bored, joyless sex. As if to lend credibility to the events onscreen, not to mention a frisson of the forbidden, the films often pretended to come from Scandinavia, as Denmark was the first country worldwide to legalize pornography in the late 1960s.

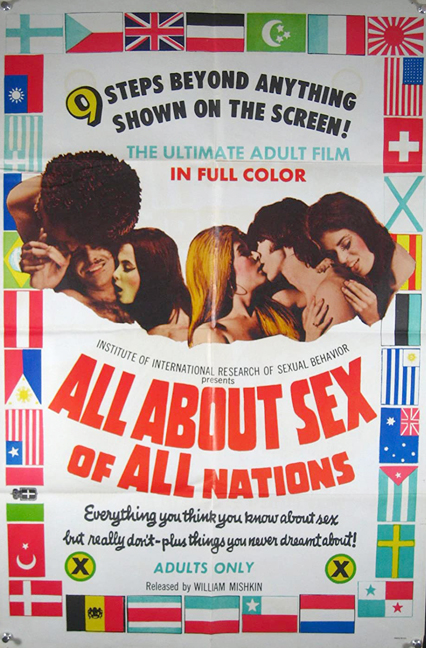

Kemal and Lucky jumped on the ‘marriage manual’ bandwagon and made several sex documentaries, including Sexual Practices in Sweden (1971) (production company: the ‘Svenska Institut of Sexual Response’ apparently) and All About Sex of All Nations (1971).

Being based in the Film Center building meant that they mixed with other sexploitation filmmakers, such as Sidney Knight, the sex film alter ego of Simon Nuchtern. Kemal and Lucky filmed sexual inserts to spice up Nuchtern’s Vietnam draft dodger flop, Love-In ’72 (1970), and they assisted Simon on his sex-documentary efforts, films such as Sexual Customs in Scandinavia (1972). Sometimes, Kemal and Lucky got lazy and simply put out an assembled collection of loops masquerading as a feature film, such as in Sex Pursuits (1971). The Arab hid behind a variety of names, including Karl Hansen, while Lucky stayed out of the credits completely.

“There was a second reason I wanted my name left off the production credits,” remembered Lucky, “and that was the mob. As soon as the business started to become riskier from a legal point of view, more wise guy characters started to show up. I didn’t want my legs broken, so I was happy for there to be no evidence of making films with the Arab.”

Tallie Cochrane, actor in several of the early sex films, as well as primary agent for industry talent, remembered the two budding filmmakers vividly: “It was always a party when Kem and Lucky came around. They were such fun and so good-looking. All the girls wanted to have them and all the men wanted to be them. They were a million miles away from the stereotypical image of sleazy pornographers.”

Jason Russell, wife of adult star Tina Russell and early sex performer, concurred: “Tina and I were good friend with them both, especially Kemal. In our first years in the business, we worked for him all the time. Whenever we needed some extra cash, we headed to the Film Center building, hung out with Kemal, and he’d find us a part in his next movie, usually a one-day wonder. He used a different name on every film he made, so it was difficult to keep track of them, but there were a lot. What we liked about him was that he wasn’t interested in shooting close-ups of genitals -which everyone else seemed obsessed by. He was more interested in showing the character’s feelings.”

“The best one he did was called All About Sex of All Nations: it was shot for $15,000 and grossed millions. It even ended up in the Variety Top 50.”

Another neighbor at the Film Center building was a new face: Kenneth Schwartz. Lucky remembered: “Kenny was long on enthusiasm, short on talent. Nice, sweet guy, though nobody liked him much. He had an editing suite consisting of five or six rooms on the ninth floor of the Film Center, and the other filmmakers used it all the time.

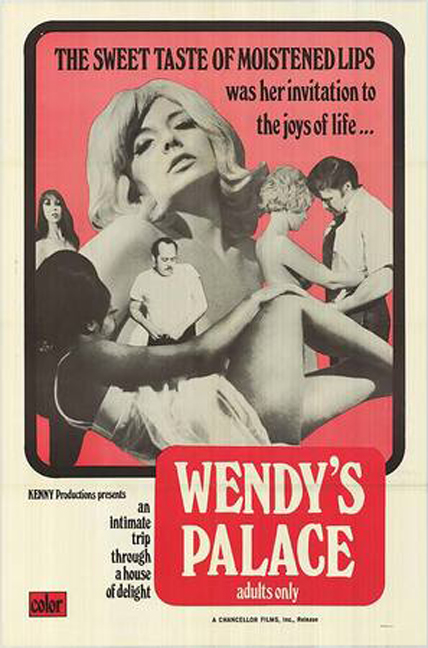

“When we first got to know Kenny, he was putting together a film called Wendy’s Palace (1970). Kemal helped shoot some of the scenes. It was a strange movie: it wasn’t really very hardcore… and it wasn’t really very good. It was on the cusp of the historical switchover that was taking place in 1970-1971: half of the people in it were leftovers from the softcore era, and the other half were getting ready for the hardcore era to start. The film pleased no one, but I heard later that it ran into legal trouble in Ohio where some idiot considered it obscene. So go figure.”

“I did the casting for ‘Wendy’s Palace,’” remembered Tallie Cochrane. “It was easy: everyone was living at the Camelot, an apartment building where I lived with my guy. So I just rounded them all up and told them where to go. I think I was in the film as well!”

Tallie Cochrane, in ‘Wendy’s Palace’

Tallie Cochrane, in ‘Wendy’s Palace’

In many respects, Kemal and Kenneth Schwartz were well-suited: they both wanted to move into fully explicit films but were aware of the risks (Schwartz just used the name ‘Kenny’ on ‘Wendy’s Palace’). Whereas Kemal wanted to be a filmmaker, Kenny preferred the production side. Together they formed a joint company in 1973 called Crescent KemKen Film Co.

*

Kemal and Kenny, and Lucky too – The KemKen Years: To go Hard or Soft?

Kenneth Schwartz died in 2009. He lived his last years in Delaware dealing with the contradiction that was his life: he was inwardly proud of his film work but couldn’t mention it to family, friends or acquaintances due to its pornographic nature. He wasn’t even sure that he wanted to take my call. Each time we spoke he insisted he was busy and couldn’t go into detail, yet he stayed on the phone for ages, clearly wanting to keep talking. He frequently asked about what had happened to his old filmmaking colleagues, but didn’t want to be re-connected with them – and didn’t even want it known that I had contacted him.

Kenneth remembered Kemal and Lucky well. Kemal, he said, was slowly becoming more comfortable with making explicit sex films, but most of all wanted to make a good film: “Kemal was more creative than me – but had less of a business brain. Which is another way of saying I was cheap, I guess.”

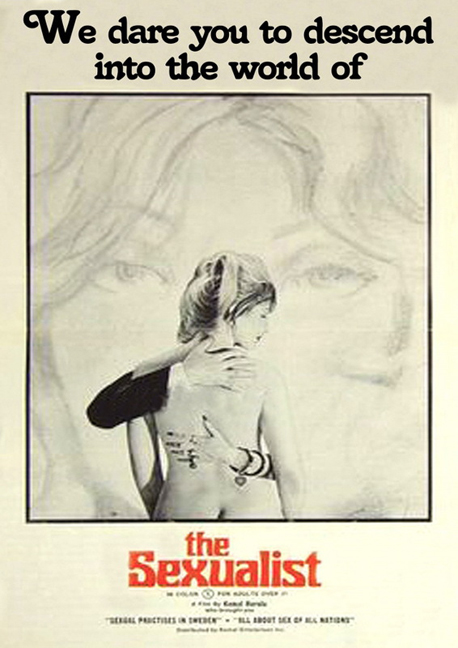

Their first formal collaboration was The Sexualist: A Voyage to the World of Forbidden Love (1973), which Kemal directed and Kenny produced. The star of the movie was Jennifer Welles, and Lucky, a crew member again, remembered the star above all else: “Jennifer Welles was an ex-burlesque dancer from the 1960s so I’d known her for years as we’d moved in similar nightclub and dance circles. She was volcanic, and the sweetest person too. Sadly, she was one of the few women who was immune to my charms…

“The Arab and I spent ages trying to convince her to perform hardcore scenes. She was understanding but refused – but we liked her so much we kept her in the lead role anyway. In the end, we shot an explicit scene with Tina and Jason Russell and inserted that into the final cut. It didn’t make much sense but it was slowly pushing the envelope towards hardcore.”

The plot of ‘The Sexualist’ imitated reality, telling the story of a director trying to make an educational erotic feature about sex but dealing with an impatient mob-connected financial backer and a temperamental lead actress.

Filming started in 1971 and continued in a piecemeal fashion over the following year. Kemal chose locations that were easy to use – such as his beloved Keneret restaurant on Bleecker Street, Jason and Tina’s brownstone apartment of in Brooklyn Heights, and the General Grant Memorial on Riverside Drive & 122nd Street, right over the road from Kemal’s apartment.

Kenneth Schwartz remembered the film as painfully slow to assemble: “Kem shot it over several months, depending on what money we had and who was available. I lost trust and never thought it would come together, so I was amazed when he edited something that vaguely made sense out of the footage.

“Our main problem was lack of confidence that the time was right to make a completely explicit film. We saw what was happening to Damiano and other filmmakers who were involved in obscenity court cases, and we kept chickening out. So in the end, this film was like a Frankenstein monster – half explicit, half soft-core.”

Lucky remembered the same dilemma: “We knew the market for soft films was disappearing, but we didn’t want to be the pioneers who got arrested for obscenity either. We liked our freedom too much!”

The sexual quandary continued into the next KemKen collaboration, The Virgin and the Lover (1973). This time it was supposedly written by Kenneth, a fact that Lucky disputed: “I think that Kenny was just trying to get his name on the credits to show some kind of creative involvement. But he wasn’t much of a writer.”

Wherever the script came from, it was a strange story about a man who has only been in love with one woman being devastated when she dies in a car accident. He obsesses over her to the point where he adopts a mannequin which he dresses like her, before consulting a psychiatrist about his problem.

Jennifer Welles returned in a smaller role – though Kemal and Lucky still couldn’t convince her to perform a hardcore sex scene, so that was left to early porn starlet Helen Madigan – and the cast was led by Eric Edwards and one-hit wonder, Leah Marlon.

Once again, Kem used locations that had meaning to him, such as Mr. Laffs, a regular nightclub hangout for him and Lucky that was opened in the 1960s by New York Yankees infielder Phil Linz and often described as New York’s first sports bar. A fight scene was shot at the Tittle Tattle, a Manhattan night spot popular among professional athletes, while other scenes were shot in Kenneth’s office at the Film Center, in Darby Lloyd Rains’ apartment, and also in Kemal’s apartment, which displayed a poster for ‘The Sexualist’ on the wall.

The Film Center, as seen in ‘Virgin and the Lover’ (1973)

The Film Center, as seen in ‘Virgin and the Lover’ (1973)

When the movie was done, Lucky realized that his movie career – of all shades – was done too: “I was turning 50, and I didn’t want to keep hustling as an actor or as a porno guy.” It had been a long journey and I was ready for something else.”

He remembered having a conversation with Kemal in the Keneret restaurant. “Kem told me that he was going all in: he was going make fully explicit sex films. He said that was where the money was, and that recent court cases had made it safer for producers to produce XXX films without facing legal issues.”

Kenneth Schwartz remembered: “After the 1973 movies, Kem was emboldened. He didn’t care about hiding behind a made-up name – as long as he felt the film had artistic merit. In fact, he insisted on his real name appearing in the credits.”

For Lucky it was the end: “I told him I was giving it up. It was sad, like a break-up. We knew things probably wouldn’t be the same again between us – because we’d been so tight.

“And that was that. Kemal kept making adult films into the 1980s. Big budget ones too. I’d occasionally open the newspaper and see his name there, and I’d smile. He did pretty well.”

*

Lucky, in the end

The Hollywood ballroom was filling up with older women in their best dancing clothes. Lucky slipped away when he saw a regular squeeze and led her proudly onto the dance floor. He moved effortlessly, holding eye contact, and whispering into her ear. He returned to the booth with a wink, looking fresher than when he left.

Since quitting his film career in the 1970s, his life had been no less interesting. He worked as a dance instructor in California, managed an apartment block in Nevada, spent years as a cruise ship host, and had stints as an aging gigolo before he moved to Florida. (“A gentleman never tells,” he smiled when I inquired about the latter. “But I charged $300 per hour.”)

After moving to Florida, he gave up the dance-for-pay gig several times in favor of a regular job. But dancing always pulled him back: “I was an assistant manager at the local Publix supermarket, and I have a stall at the Sunday flea-market,” he said defiantly, though he was clearly not comfortable talking about these unglamorous gigs for long. He was prouder to talk about winning a string of senior citizen body-building competitions (“I can still bench 270 pounds,” Lucky said, flexing his muscles.)

Lucky said he’d lost touch with Kemal sometime in the 1980s when the Arab moved to Los Angeles. Lucky remembered Kemal telling him the sex industry in New York was dying and that he needed to move his operations to the west coast. But when Kemal got there, he found that his interest in filmmaking had waned.

“It’s not like the old days,” Kemal complained.

“I don’t think it ever was,” replied Lucky.

The last time they spoke, Kemal had bought a boat which he kept out at Redondo Beach, got himself a girlfriend named Christina, holidayed regularly in South America, and was living a quiet, contented, retired life.

I told Lucky that the Arab had died in November 1991. Kemal had returned from a trip to Mexico feeling unwell. He went to the doctor, and shared the diagnosis with close friends: pancreatic cancer. Same problem that Michael Landon had, Kemal told anyone who listened. Christina cared for him, but the Arab’s end was swift.

Kemal left half of his possessions to Christina and half to his mother – about half a million dollars in total. His body was returned to Istanbul, where he was buried in the cemetery in Ajan according to his dying wishes.

Lucky listened to the news and was quiet for the first time. For the longest time.

He stared into the distance, his face expressionless, his white shoes finally still.

“Everything and everyone is such a long time ago,” he finally muttered.

His quiet spell was broken by a beaming, rotund women in a large sparking top who had suddenly appeared at his side.

“Could I have this dance?” she asked with the nervousness of a girl at a high school prom.

“You would make me the happiest man in the world,” Lucky replied. He put his arm around her waist and slid off into the sea of dancers.

*

Lucky Kargo returned to Las Vegas shortly after I interviewed him: “I have exciting new show business offers,” he said with a laugh.

He passed away on June 30th, 2009.

*

Unbelievable. Really special research and writing. The number of stories that are still emerging – here! – is breathtaking.

We so appreciate that Krule!

Lucky and the Arab stands as one of the best articles I have read on film.

Both men and their legacies would be hugely grateful to you for this.

Thank you.

Thank you so very much Niu!

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work Happy Memorial Day

Thanks Jeff!

An amazing history to reveal. Thank you Rialto Report.

Thanks for reading Thomas!

A grand slam. Great article. Thanks!

We really appreciate it Lee!

Thank you for transporting me to another world with such great writing. Fantastic work!

Thanks so much Don!

Thanks! What a well-written, and researched, moviemaking story. Wish these guys were still around, would love to have met them. Love Rialto Report.

Thanks a lot Martha!