Why isn’t Chesty Morgan a feminist icon?

No, wait, come back. I’m serious.

Chesty Morgan may have been a stripper with a famously large bosom, but there’s much more to her story than that. She became one of the most famous burlesque dancers of the twentieth century on her own terms, through hard work and perseverance, enduring sexism, harassment, and persecution, while single-handedly raising a family.

Add to that, she grew up persecuted by Nazis, was at the center of a notorious murder case, and other moments of great personal tragedy along the way.

So why is Chesty Morgan a footnote to history – mentioned principally for having acted in films by the likes of Federico Fellini and Doris Wishman?

The Rialto Report spoke to Chesty Morgan, now aged 84. This is her story.

——————————————————————————————–

1991 – End of an Era

Chesty Morgan was 54 years old when she took her final bow on stage.

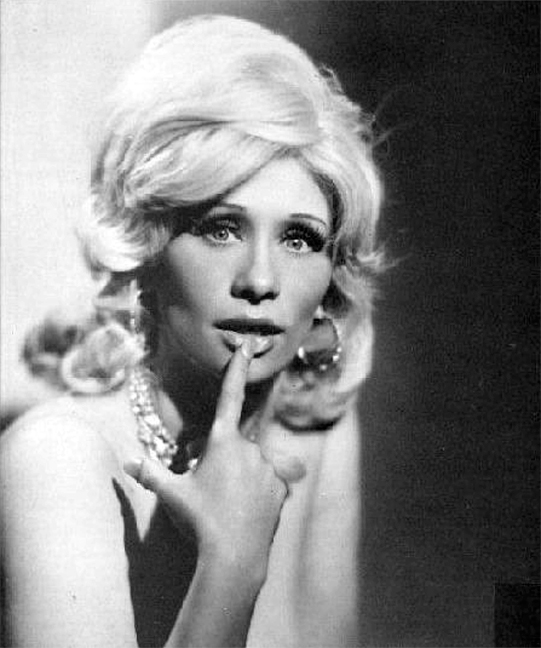

She still had the same 73’ chest, red and black sequined dress, and improbable blonde wig, but now she was tired. It had been a long ride and the asphalt highway had taken its toll. The aging burlesque star was finally ready for a quieter life.

For twenty years, she’d disrobed in hundreds of theaters, survived ridicule and sexist slurs, been arrested for lewdness and obscenity, and suffered immeasurable personal tragedy.

When the curtain came down on her final performance, she could allow herself a rare moment of self-reflection: she had survived. More than that, she had saved her money, raised a family, and maintained her dignity. And who can say that after two decades of stripping?

It had been a long, bumpy ride.

——————————————————————————————–

1965 – Lilian Wilczkowski

In 1965, she was Lilian.

Lily to her husband. Miss Lilian to her neighbors. And Lilian Wilczkowski on her newly minted U.S. passport, if you cared to attempt a surname that looked more like a discarded Scrabble hand.

Lilian had different names because she had different roles in life.

To her husband, Josef Wilczkowski, she was his faithful wife of eight years. Mother of their two girls, Eva and Lila. She was caustic, sharply opinionated, occasionally argumentative, and fiercely supportive.

To her neighbors, she was a short, severe, mysterious, elegantly dressed woman with a substantial chest, and an eastern European accent as thick as goulash. Idiosyncratic diction was common in the Jewish and Italian area of Canarsie, south Brooklyn, which Lilian and Joe called home, but Lilian’s pidgin English, spat in a glottal brogue, was impenetrable to most.

At the age of 28, Lilian was grateful. Grateful for a life that had seemed impossible after suffering unspeakable trauma in her first twenty years. She finally had stability. For that, she credited America, God, and her husband. In that order.

Joe was studious, sober, serious, and seven years her senior, an observant Jew who prioritized family and hard work over romance and dreams. That suited the unsentimental Lilian just fine. Joe owned a business, Spring Valley Poultry Farms, a butcher’s shop at 1568 Fulton St, in the heart of Bedford–Stuyvesant, a black neighborhood in Brooklyn. He ran it with a friend, Jack Needleman. The business did well, the impressive variety of meats and a ‘Fresh Chicken Killed Daily’ window sign clearly worked a treat. Joe and Jack worked long hours and employed several staff, including a master butcher, Isadore Rosenhouse.

Local support was vital to the success of a business in the area for a simple reason: Bed-Stuy was always in the news for its out-of-control violent crime problem, described as “unpoliceable” by the New York Times. Unless you were careful, a thriving Jewish butcher shop in the heart of an impoverished black slum could attract the wrong kind of attention. But Spring Valley Poultry was popular largely because of its stand-up, generous, honest-to-God owners. Joe and Jack made a point of giving food away to local events. They extended credit to their poorer clients. They hired butcher apprentices from the local area, often ex-wannabe hoodlums or just kids needing a break, such as the Anthony brothers, Kazle and Wilfred.

Lilian was used to working hard so she asked Joe for a job in the family business. He turned her down gently, asking her to stay at home with the girls. Lilian idolized Joe and consented with grace. She would be the perfect housewife for him. The meat money was good, and at the end of 1964, the family moved into a new bigger home.

Brooklyn life may have been mundane for Lilian, the Brooklyn butcher’s wife, but sometimes humdrum is all the excitement you need.

*

March 27th, 1965.

Saturday, the busiest day of the week for any retail business like Spring Valley Poultry.

9.30pm, Joe and Jack were closing for the day, the registers full of the day’s cash business.

Back at home, Lilian put the kids to bed and turned in. Joe was always late home on Saturday evening as he stayed to clean the store, and Lilian was typically long asleep by the time he returned.

Not so his partner Jack’s wife, Evelyn. She waited up for her husband every night. And on this day, when midnight came around, and Jack still hadn’t returned to their Queen’s apartment, Evelyn called the police.

Forty minutes later, a patrolman stood at the entrance to Spring Valley Poultry Farms on Fulton Street. The front door was closed but unlocked, so the patrolman entered the store. Inside he saw a light in the 10×10 foot walk-in refrigerator at the back of the building. He pulled the heavy door open and revealed a sight that he would never unsee. Inside were three bloodied dead bodies: Joe, Jack, and their master butcher, Isadore Rosenhouse. Each of them was still wearing a white apron, each had been shot in the back of the head twice, and each of them had deep cleaver wounds in their skulls. Cash amounting to over $3,500 was missing from the premises.

In the early hours, Lilian was woken by a call from the police. She was told to come to the precinct. Bleary-eyed from tiredness, Lilian turned up and was asked to identify Joe’s mutilated body.

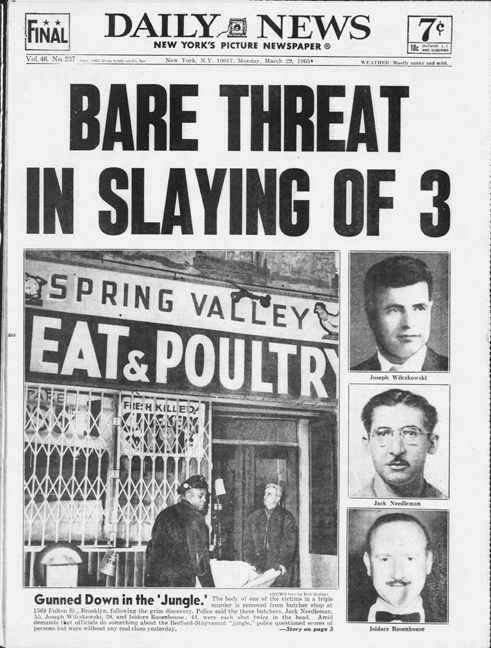

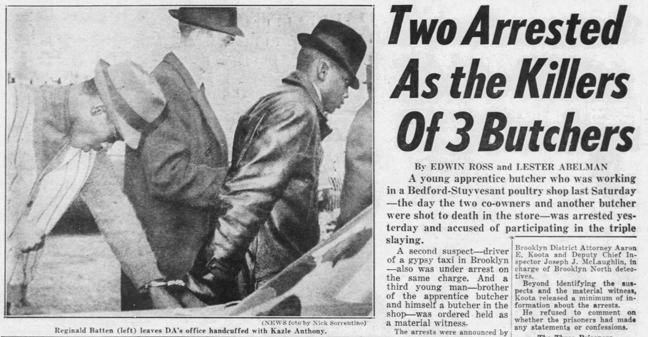

News breaks of Joe’s murder, with picture of Joe (top)

News breaks of Joe’s murder, with picture of Joe (top)

*

Reaction to the violence was swift.

The media dubbed the killings the ‘Ice Box Murders’ and dedicated front page headlines and gory accounts of the gruesome details. The local community turned on the police, enraged, demanding swift action. Relatives called on the mayor to step up and fix the problem. The NYPD knee-jerked and ordered fifty detectives to drop their caseloads and concentrate on this case.

And then there was Lilian. The newly-widowed mother of two mixed grief with fury. She turned up at the precinct several times each day, demanding updates, and raising hell if no visible progress had been made.

She organized Joe’s funeral, an event attended by hundreds of local residents, where several of the mourners gave heartfelt eulogies. Poignant words were delivered by young Spring Valley Poultry apprentice Kazle Anthony, who praised his former bosses in glowing terms: “They were fine men. They took me off the streets and treated me very well. Only someone insane could have done this.”

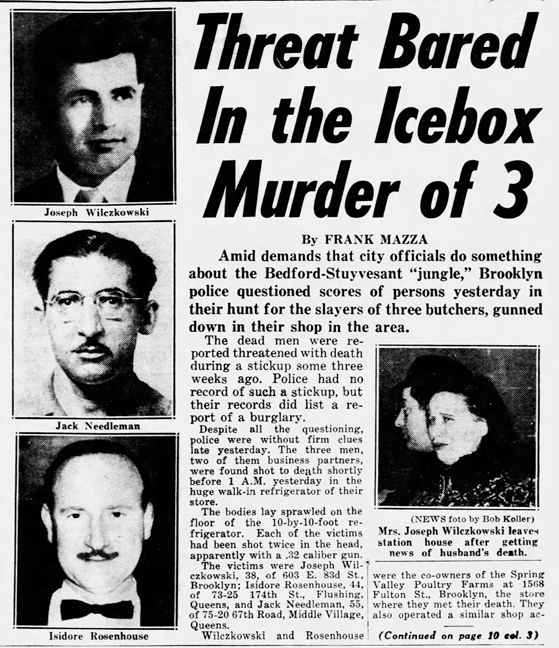

Media coverage of the Ice Box Murders, including picture of Lilian after receiving news of Joe’s death

Media coverage of the Ice Box Murders, including picture of Lilian after receiving news of Joe’s death

The dragnet murder investigation fanned out across the neighborhood, where scores of local men were taken in for questioning. The Spring Valley Poultry store was tooth-combed, but the only clues were rare .32 caliber shell casings of foreign manufacture used in the crime. Then finally a break in the case: a nearby Army-Navy store clerk recalled selling .32 ammo with the same unusual casings. He said the sale had only taken place a few days before. His cash register records revealed the identity of the buyer: one Kazle Anthony. Hardworking, grateful, grief-stricken, butcher’s apprentice, Kazle Anthony.

Kazle Anthony was cooperative, admitting the shells came from a gun that he’d once owned. But he said he’d thrown the gun away a few days before. Perhaps someone had found it discarded at the butcher store and used it in the robbery?

The police squeezed Kazle. They pretended an accomplice had confessed and implicated him. Kazle cracked. He admitted guilt and confessed: he blabbed that he’d marched the three victims into the refrigerator before robbing the store. He said he’d shot them because they would’ve identified him. Kazle ID’d his partner in crime too, the guy who’d used the meat cleaver: Reginald S. Batten, an unlicensed Brooklyn taxi driver. The detectives took off and, armed with a search warrant, descended on Batten’s apartment where they found a valise containing $3,584. Kazle and Batten were locked up.

But the arrests didn’t bring any closure to Lilian. At the trial, she made her presence felt. At first, she hissed “murderers” whenever their names were spoken in court. Then her whispers became bitter shrieks of righteous anger. She was disruptive enough that the judge had no option but to remove her from proceedings. So Lilian changed tack and shared her vitriol with the eager members of the tabloid press.

Kazle Anthony and Reginald Batten were convicted of murder. The sentencing Justice described the crime as “the most vicious and calculated crime I have ever tried.” Nevertheless, he had a problem issuing the most severe punishment: shortly before the trial, New York State had abolished the death penalty for all but police killers, so the two men were sentenced to 26 ½ years-to-life in prison instead. If the victims had survived, they would have received 75 to 150 years. It was a bizarre quirk in the law at the time. The public seethed. Lilian was outraged. The judge apologized, and urged the state legislators to rectify the penal code.

Kazle and Batten went to jail. Lilian was left to raise two girls by herself, without a husband or an income.

——————————————————————————————–

1937 – Sarah Wajc

In the beginning, Lilian was Sarah Wajc (pronounced ‘Weiss’), only daughter of a Jewish couple, Lipa Wajc and Chava Berkowitz. She was born October 15, 1937, in the town of Leszno, Poland, 250 miles east of Warsaw.

Two years after her birth, Leszno was annexed by Nazi Germany, the front line of the joint German-Soviet invasion of Poland that started World War II. Overnight, invading soldiers carried out mass arrests of anyone accused of “anti-German activities” in the town. Sample offending behaviors: attending religious services, holding private meetings in households, or being Jewish. Many Jews weren’t just arrested: a number of them were massacred by the Nazi Einsatzgruppen immediately after they entered the town in September 1939.

Sarah was born too late to know the good days, when her father sang at weddings, painted portraits, and played soccer for the local team. She doesn’t remember the intelligent, loving home into which she was born. She doesn’t remember her parent’s successful department store business that provided a comfortable pre-war lifestyle for the extended branches of aunts, uncles and cousins.

And she doesn’t remember the day her name was changed to Ilana, her mother’s to Eva, and her father’s to Leon, to hide their Jewish identity from the Nazi occupiers. Most of all, she doesn’t remember the day her mother ventured out to buy her niece new shoes and was apprehended by German soldiers, who bundled her into a car and drove away. Ilana’s father, Leon, tried in vain to leverage a local German contact and buy her release. No deal. Eva perished in a gas chamber just weeks later.

Shortly after, Ilana was separated from her father: he hid with an ever-changing network of friends, joining the underground guerilla offensive against the occupying forces, while Ilana was passed between her mother’s and father’s sisters in Leszno and Warsaw. Occasionally she was reunited with Leon, like when he turned up at a Warsaw house where she was hiding with three cousins and two aunts. Fearing for their safety, Leon dug a hole in the floor beneath her bed, creating a concealed hiding place in the basement. He told them to hide in the small, dark space, instructing them to remain silent as he left again. The family listened in darkness as the German soldiers marched past the house, occasionally stopping to peer through their windows.

What Ilana does remember is the hardship. Scavenging food from the streets. Pretending to be dead when soldiers broke into the house. Hiding in a series of flooded, cold, underground grottoes beneath the streets of Warsaw, sometimes not seeing daylight for months on end. She remembers saving scraps of food in case her parents were hungry when they returned for her.

It got worse. As a young child, she was considered a burden to her aunts who pushed off to a series of orphanages, some caring, many neglecting. Ilana describes her early years as an unloved Cinderella. That would be true if Cinderella’s mother was killed by Nazis, and she was malnourished, unloved, and in constant fear for her life. Leon never showed up again, shot and killed in combat, another anonymous casualty of the long conflict.

*

At the end of the war, Ilana was seven. Without parents, she continued her lonely orphanage existence, now taking care of the younger children around her, cleaning their clothes, washing their hair.

At age twelve, there was the hope of a new beginning: Ilana’s aunts relocated her to Israel, a youth kibbutz in Neve Hadassah in the middle of the country. The mission there was for children to attend school in the mornings and work the rest of the time. Ilana was assigned to laundry duty. She studied hard, and took part-time work tutoring kids to earn money for the first time in her life.

Five years later, she left the kibbutz and moved in with an aunt nearby. She started nursing school, working in Hadassah Hospital. People with her skills were in short supply, so she found herself looking after sixty toddlers each night.

Ilana’s dedication to hard graft meant she didn’t have time to socialize, let alone date. She says she looked like a fishing rod until she was 16, and then overnight, something unexpected happened.

To say she bloomed would be an understatement: “I was flat-chested like a boy. I used to feel shy about that, but then, it all changed. Suddenly I was embarrassed about the size of my breasts. I was a shy girl, and I wasn’t prepared for that. Every time I went outside, I could feel people looking. Men would gather to watch me walk by. Some of them would follow me around. At first it was miserable, but after a while I began to like it.”

At nineteen, her cousin introduced her to a visitor to the area: Joe was a Polish refugee living in Brooklyn who was visiting his family in Israel. His backstory was no less scarring than Ilana’s: he’d survived the Holocaust in a Nazi death camp, moved to Israel briefly, before carving out a new life in the United States. Joe took a shine to Ilana. Ilana took a shine to the American life that Joe talked about. After four days, Joe proposed and Ilana accepted. They wed quickly. Within weeks, Ilana was a married woman living in Brooklyn, having changed her name again, this time to Lilian.

The whiplash life change may have been difficult for someone less hardy: the city had more people than she’d ever seen before, and Lilian knew no one except for Joe. Further, she couldn’t speak English and frequently got lost on the New York subway where she couldn’t ask anyone for help.

It was a culture shock, but after the first twenty years of her life, it was a perfect one too, and Lilian didn’t look back.

She remembers, “After everything that happened in Poland, I thought what could go wrong, you know?”

——————————————————————————————–

1966 – The Widow

Joe’s brutal murder crippled Lilian.

She’d worshiped him, believed in him, and placed her trust in him. Joe had saved her, adored her, and given her a loving home.

After his death, she contemplated suicide on a regular basis. “It was terrible. Really terrible. I was completely lost,” she says. “I didn’t think I could live without him. I didn’t think I wanted to live without him.”

Grief mixed with irrational anger: “I couldn’t believe that my husband would leave me alone. I knew it wasn’t his fault but I was angry with him. Why did he leave me to struggle?”

Lilian decided she had to live for the girls – Eva was four years old, Lila just four months – but her options were few: her English language was still poor, she had scant job skills, dwindling money, and her kids were growing fast. New York was an expensive place to survive.

Friends stepped in and introduced her to eligible single men; many wasted no time proposing marriage. Lilian could have taken the easy way out. Marry and ease the struggle. Find the least unattractive man and hitch her ride to a comfortable middle class existence. But Lilian was adamant: “I thought I never wanted to marry again. I couldn’t depend on anyone. I knew I could only trust myself from this point on. Joe had given me everything, and I wanted to keep it.”

And so a brand of feminism was born, a fight for self-sufficiency and financial independence without relying on any man. Lilian resolved to take care of her family, whatever the personal toll. Gone were her distant private pipe dreams of training to be a doctor or lawyer. Now she was a single parent faced with the reality of working two, sometimes three, jobs. For the next five years, she did whatever she could: she toiled in real estate sales, as a clerk in a New York department store, as a secretary for a distribution company. It was an uphill battle, and she still didn’t seem to have two nickels to rub together. Hiring sitters for her daughters was expensive and she couldn’t even afford to run a car. It was time for a re-think.

In 1972, one suitor, Maury, took her to a nightclub. It was her first time. Lilian didn’t drink, smoke, or cuss, and had little idea such places existed. They watched a striptease. Maury suggested she could do that. It paid good money, he said. Much more than the dead-end jobs she was taking. Lilian was disgusted, and told him she never wanted to see him again. But the thought lingered.

She discussed it with friends. Some encouraged her to exploit her prodigious dimensions. At first, Lilian’s reactions were split into two contrasting directions: fear and greed. As time went on, the latter eclipsed the former: what if the best way forward was to use her largest assets? “I figured, I supported this body of mine for years. Now it could support me. But I only was going to try this for two weeks – and then I was getting out.”

That decision would change her life forever. Asked if she has any regrets today, Lilian says only, “I just wish I had started in show business sooner. But better late than never. What else could I have done to make as much money?”

——————————————————————————————–

1972 – Chesty Morgan

There is no way to get around it. This is a story about breasts. For reasons that psychologists, sociologists, and pornographers have noted for time immemorial, the external casing of the mammary glands have an appeal to a sizable segment of the male population. Lilian had lived a sexually sheltered life, but even she recognized that American men love breasts.

Somehow she found a gay choreographer, bought a cheap evening gown, and called a small Manhattan theater. It wasn’t an auspicious start – she took the subway from her Brooklyn home, and refused to take off her bra on-stage (“Before I started in this business, I never even took it off for my husband”) – but her new career had begun.

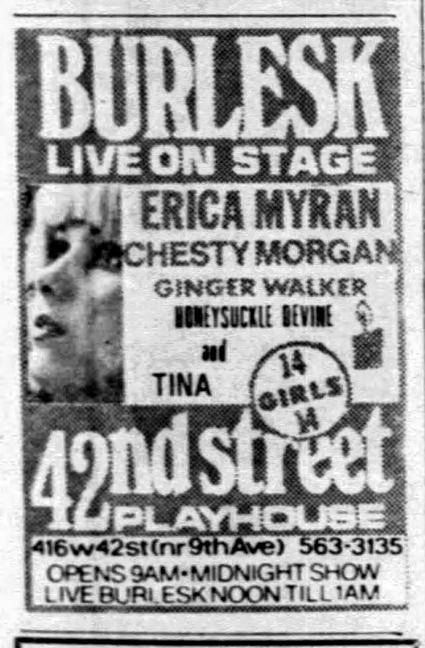

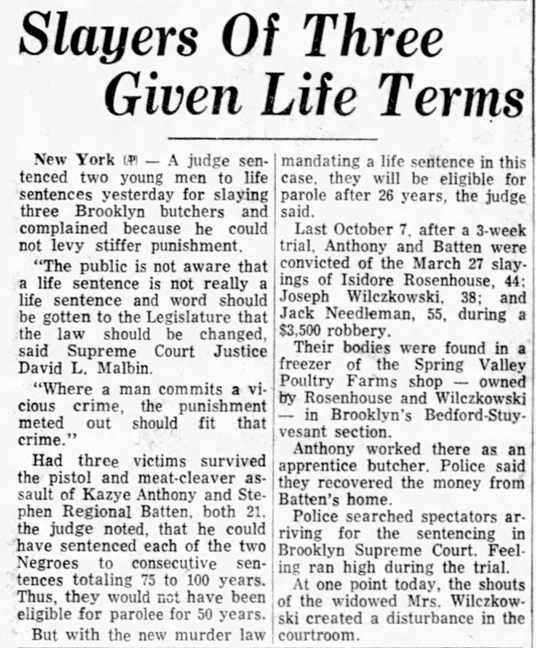

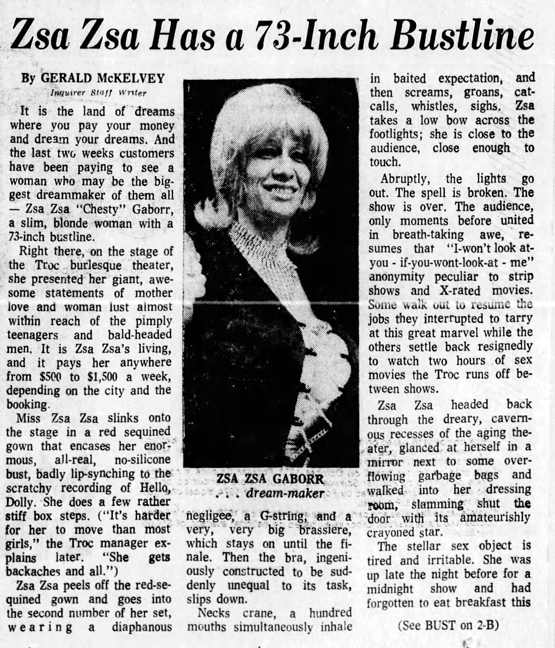

The next bookings were a little more successful. For her first appearances at the 42nd St Playhouse in Manhattan, she was billed as ‘Zsa Zsa,’ an oblique nod to Zsa Zsa Gabor, the airhead Hungarian actress, socialite, and beauty queen. Within weeks, this reference became more explicit, and she was billed as “Zsa Zsa Gabbor” – the two ‘Bs’ in the surname were a none-too-subtle desire to avoid a lawsuit.

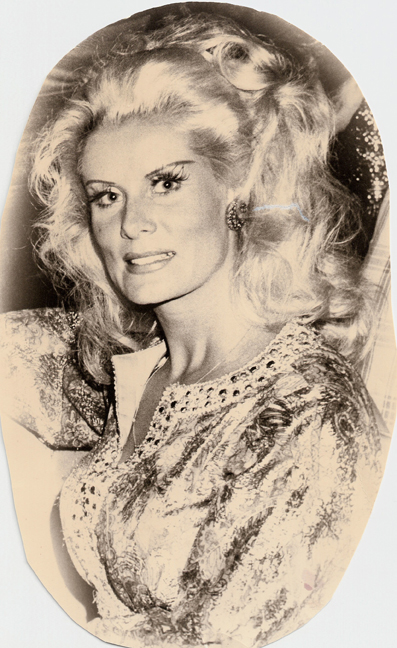

It wasn’t long before her name changed again. A nightclub owner suggested ‘Chesty Morgan.’ Why undersell her biggest assets, he argued? Lilian agreed, and Chesty Morgan was born.

January 1973: early ad for Chesty Morgan

January 1973: early ad for Chesty Morgan

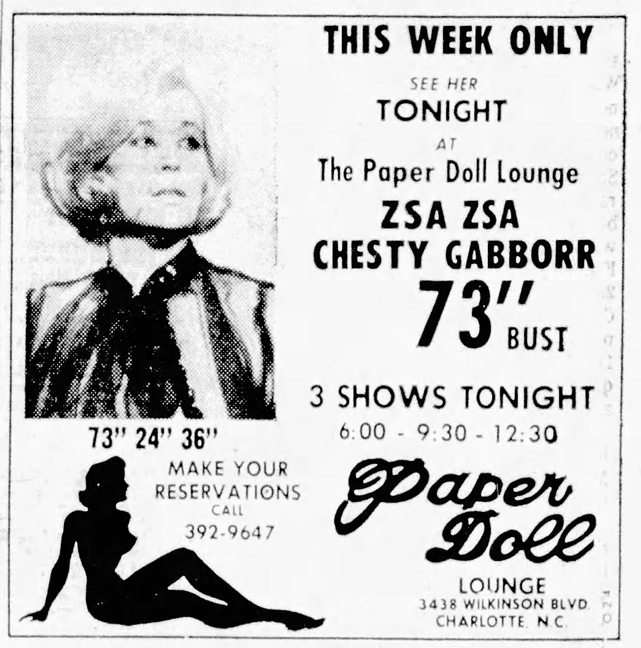

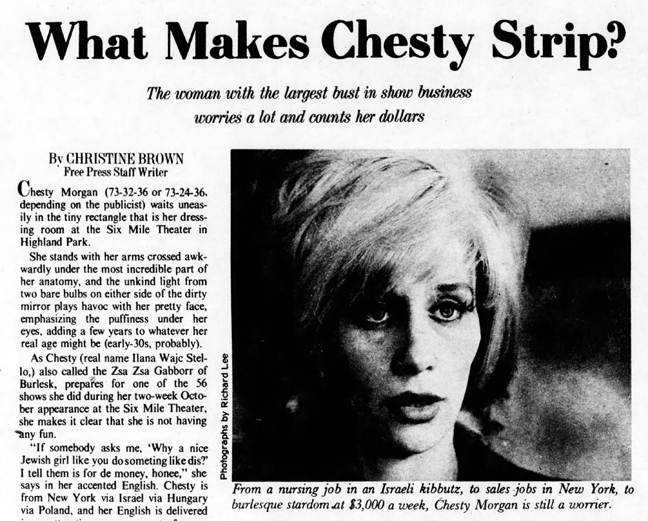

When it came to marketing her show, the message was simple and direct: “Vital statistics 73-24-36 – Yes, you read that right, 73’, this is not a misprint!”

In truth, the selling of Chesty Morgan was hardly complimentary, or even sexual. It had more in common with an old school carny freak show, exploiting its performers’ disabilities for profit. It was simple misogynistic exploitation, but it worked: “The world’s chestiest exotic. She defies medical science! Fabulous! Incredible! Amazing! Fantastic! You have to see it to believe it! 5’8” 118lbs 73-24-36!”

Not that Chesty was complaining: “Honey, I got paid a lot of money,” is her honest assessment today.

Sure enough, within weeks, Chesty Morgan was an unprecedented sensation on the burlesque circuit, benefiting from the promotional savvy of an agent/manager, Al Baker Jr., and his affiliated theaters. Chesty refused to be exclusively contracted to Baker as she wanted to retain control of her new career: her desire for independence was non-negotiable.

She criss-crossed the country making sell-out appearances – from Philly (“a very excitable town”) to Kansas City (“polite and reserved”), and outposts in between like Charlotte NC, Akron OH, Tampa FL. At first, Chesty didn’t mind the travel, preferring locations far away from her home city of New York for a simple reason: “I was so scared my friends would see my picture and find out what I was doing.”

Experience – and money – built confidence, and Chesty established her own rules from the outset: she would never remove her bottom half, there were to be no ‘private’ rooms with customers, and she would accept no payments in drugs or booze. Cash only.

Chesty’s act developed: she hired a new choreographer, upgraded her wardrobe to include custom bras and expensive costumes, learned how to tell jokes (sample: “You know why my feet are so small? Because things don’t grow in the shade”) and even tried singing. The bigger theaters got wise, and larger audiences flocked to her shows. After only nine months on the burley circuit, one club owner said, “She’s breaking every record across the country – Chesty Morgan is the hottest act since Tempest Storm.”

The media took note too and articles were plentiful. The one downside was a lack of respect from writers who were sent to check out the Chesty Morgan phenomenon. As successful as she was, she was an easy target for sneering newspaper reviews and sexist jokes.

“What does Chesty Morgan do as an act? She probably sits in a chair center stage, spotlight on her, and tries to stand up.”

“When she gets a chest cold, she uses three cartons of menthol rub.”

“One time she released her treasures close to the footlights, and a man in the front row was treated for concussion.”

So what exactly was Chesty’s early show routine? Her regular act was described in a newspaper:

“Miss Zsa Zsa slinks onto the stage in a red-sequined gown that encases her enormous, all-real, no-silicone bust, badly lip-syncing to the scratchy recording of ‘Hello Dolly.’ She does a few rather stiff box steps. (“It’s harder for her to move than most girls,” the manager explains later. “She gets backaches and all.”)

“Zsa Zsa peels off the dress and goes into the second number of her set, wearing a diaphanous negligee, a G-string, and a very, very big brassiere, which stays on until the finale. Then the bra, ingeniously constructed to be suddenly unequal to its task, slips down.

“Necks crane, a hundred mouths simultaneously inhale in baited expectation, and then screams, groans, catcalls, whistles, sighs. Zsa Zsa takes a low bow across the footlights. She is close to the audience, close enough to touch.

“Abruptly, the lights go out.”

Other reports were more withering, treating her show like a sighting of the Elephant Man:

“The choreography of Chesty Morgan might have been devised by a dancing bear. Hardly a titillating terpsichore. Two incredible mammi-form protrusions: no mere pliable mass of feminine tissues and fat there, but rather a living arterial sculpture. They are secured to her pectoralis major like acquisitions.

“When she undulates out of her costume and starts to give the proscenium arch the business, the audience howls, for hers is not a striptease, it is no kind of tease, it is an animated cartoon, like the old Tom & Jerry cartoons where Tom, the cat, sees the bulldog coming and about a hundred sets of round white eyes – boiiiiinnnngggg!! – go springing out of his eye sockets.

“Everybody crowds to the front rows, even the women, to study this phenomenon. All right, it’s freakish.

‘She can’t dance a lick,’ says a guy.

‘It’s a miracle she can even stand up’, snickers his lady friend.”

The local newspapers were full of lines about the stripping juggernaut, but the only line Chesty Morgan cared about was the bottom line. And no one could dispute, ridicule, or belittle her on that front. Within two years, she regularly earned an average of $3,500 a week (over $20,000 in today’s money). For her two-week engagement at the 6 Mile Theatre in Highland Park, MI, owner Albert Broder paid her $7,500. And Chesty worked incessantly. She rarely turned down a job, even when it meant long travel and exhaustion. In 1974, she sashayed through 56 shows in a two-week period at the Six Mile Theater in Highland Park, Detroit. Not that she enjoyed it: “If somebody asks me, ‘Why’s a nice Jewish girl like you doing something like this?’ I say it just makes it more convenient to earn big money. But I sometimes wish I had a smaller bustline because I’m beginning to develop back trouble,” she told one interviewer.

At six feet around her chest, it was admittedly hard for Chesty Morgan to live with her bosom. But if Chesty had learned anything, it was that it was difficult to make a comfortable living without it.

*

Next week, the concluding part of the story of Chesty Morgan.

I thought I knew all about Chesty but this article is simply phenomenal – a wealth of detail told in a gripping manner.

I can’t wait for next week – bring it!

Thank you Jeff!

That’s awful about her husband. Those poor girls grew up without a father.

I know for a fact Dolly Parton stole that “don’t grow in the shade” joke from her and Dolly’s are fake. Morgan’s boobs are a miracle of nature.

She lived in a time where she could set boundaries for her new career. I’m happy that she could and still make a lot of money for her girls.

An excellent interview and piece of writing. Congrats.

We appreciate that Hans!

What a staggering life…… and all this was BEFORE she became Chesty Morgan.

Breathtaking. I can’t even imagine what is coming up in the next installment.

I know that each week an immense amount of research and interview time and writing are necessary. I can only thank you for a job well done. THANK YOU!

Thank you so much for that Steve!

I was a very young and impressionable exotic dancer working at the Mitchell Brothers’ O’Farrell Theatre in San Francisco (circa late 1970s-early 1980s). Vinnie Stanich, the booking agent, had an intense passion for the Burlesque Queens of days gone by (Tempest Storm, Edy Williams, Honeysuckle Divine, etc. etc.) and booked them regularly as Feature Acts. Chesty Morgan was always my hands-down favorite. Incredibly smart, beautifully endowed, and wickedly funny. As youthful apprentices, my fellow sex workers and I would watch in awe as Chesty mesmerized her fans (and us). What a story…

What a great memory TC – thanks so much for sharing it!

I worked with Doris on the films she made with Chesty – and I have lots of stories. Their relationship was difficult … – … much the amusement of the crew. Would love to share details, just let me know via my email address. Great story.

Thanks kf!

At last a piece which bothers to look at Chesty – the woman. It has been disheartening over the years to read so many inane articles that just review her films – and treat her as a piece of meat at the center of it (I’m looking at you Dangerous Minds!).

You have done a beautiful job in conveying just how incredible Chesty’s life was BEFORE the films, and for providing all the context.

Only The Rialto Report.

We really appreciate that Tammi!

If only all performers had biographers of the caliber of TRR to document their lives.

Thank you TC!

Is it okay that I read this entire article with Ashley’s voice in my head? I really enjoy (now prefer?) the podcast episodes! These are great–but there’s something about someone ‘telling you a story’…

Just you wait…

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work

Thanks Jeff!

Great article, as usual. Looking at the map it seems that Leszno, Poland is west of Warsaw, not east.

Goddess!!!! Thank you Doris for introducing me too her. Stay Cool & Ciao.

Once again, the Rialto Report locates a fascinating person from the industry’s past. I’d seen one of Chesty’s films, but never thought beyond the blond woman with the massive breasts on the screen. I cannot wait to read the conclusion of this article because you have me hooked (as you have for virtually all of your articles)!

I love the way the articles are written to really show who the subject actually is, beyond all the visual trappings. And that enables us readers to sympathize and empathize with whomever the subject is. Thank you!

And this article makes me wonder if you’ve written others about women in the stripping scene before and during WWII. Like Sally Rand, Gypsy Rose Lee, and one of my favorites, Margie Hart. There’s a book called “Low Man on a Totem Pole” by H. Allen Smith, and he interviews not only those three ladies while they were still active, but a few of their proteges. But I have not found substantive information about them in their later lives, stuff that won’t show up in their Wikipedia entries.

Excellent piece. I had no idea that a hideous crime was the root cause for a housewife and mother becoming a big-boob icon.

Great article, as usual. Looking at the map it seems that Leszno, Poland is west of Warsaw, not east.

Wonderfully curated with the music! Such a tragic life of loss, but she kept on going! A cliffhanger of an ending too!

I saw her show some 50 years ago. I caught this article trying to find the name of the venue in Gander, Newfoundland where Lilian (under the Chesty Morgan name) did her stuff in about 1973/4. She took a shine to a pal, and though we only had a few days there (aircrew), they spent a lot of time together. All he could do was sing her praises as witty, and great company. She certainly left an impression on him and everyone else who saw her. What an heroic lady, and still with us too.

I sure admire her for standing tall after the tragedy of her life. It isn’t as if she were even a sex worker, she just took advantage of our fascination of large breasts. She seems to have been too strong for her career choices to have crushed her spirit. If anything, her careful rules and morals seemed to ensure her safety while building her confidence and self-worth. I know the beginning of this marvelous biography was a bit tongue-in-cheek, but for the life of me, I have no idea why she isn’t a feminist icon. Nothing I’ve read here caused me to view her in a sexual way, even the photos. I just see her as a strong woman that used what she had to support her children and survive after great obstacles that would have crushed many people. As a friend, family member, or simply reading about her life on the internet, I can’t imagine how anyone could help but admire this woman.