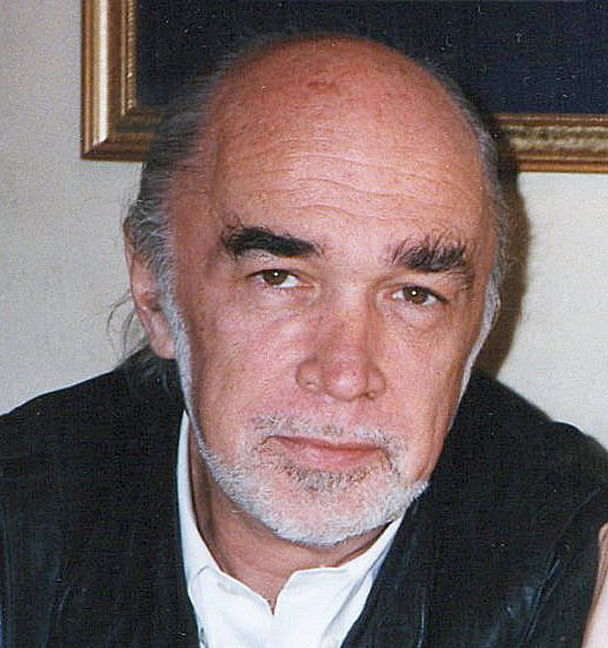

Charles DeSantos (born Charles Webb) was a unique filmmaker for a number of reasons.

He was part of the Marxist filmmaking collective in San Francisco.

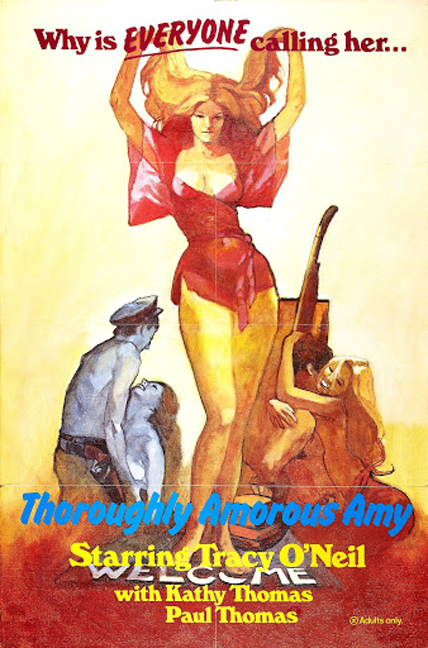

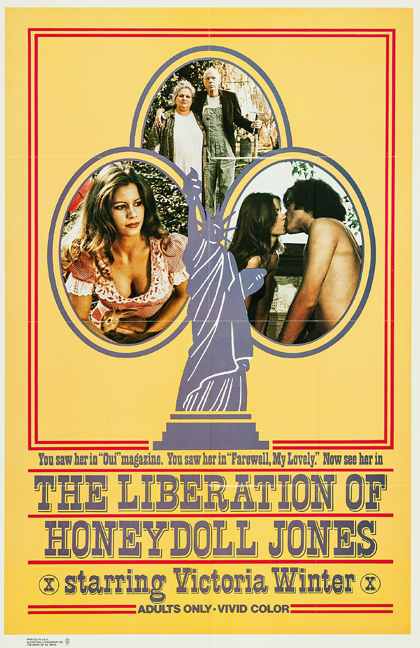

He enjoyed one of the longest careers in the golden age of adult film – from the dawn of the business in the early 1970s through the video era of the late 1980s – and made some of the period’s biggest hits, including China de Sade, The Liberation of Honeydoll Jones, The Sinful Pleasures of Reverend Star, and Thoroughly Amorous Amy.

He based one of his films on the movie ‘Apocalypse Now‘ – several years before Francis Ford Coppola‘s film was released, and made another, Honky Tonk Nights, that featured legendary folksinger Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and pioneering stripper Carol Doda.

He was one of the first adult filmmakers to travel to Europe to make movies, taking John Holmes and a group of American porn stars that included a pair of twins to France.

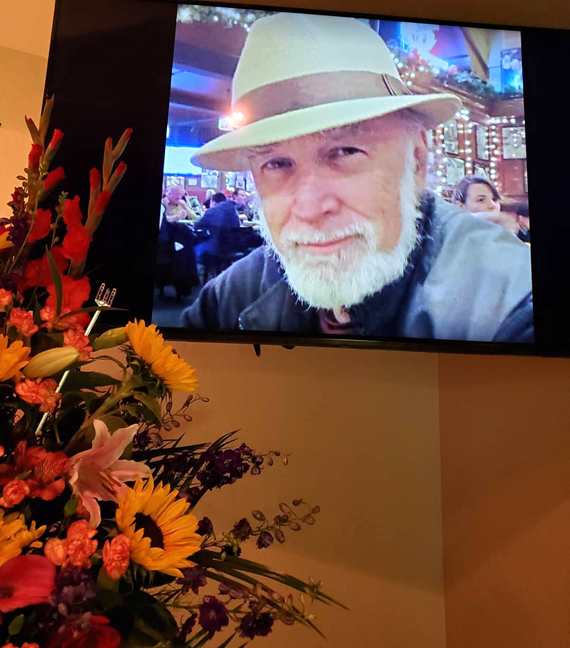

Charles sadly passed away last year, but The Rialto Report interviewed him many times over the last two decades.

This is the story of Charles’ ground-breaking career in the 1970s, his first decade as an adult filmmaker.

___________________________________________________

1. Charles DeSantos: Beginnings

Where did your interest in film come from?

I was in a PhD program at the University of Pittsburgh. I was in the area of Psychobiology, Sensation and Perception and so on. This was back in 1967.

I’d always been interested in filmmaking. I was using a 16mm Bolex camera to do some of the research for my degree. I got to know people in the university community who were into filmmaking, and so I became one of the partners in a film program. We brought the underground movies of the day to the university – anything from Warhol films to Canyon Cinema movies – and exhibited them to students.

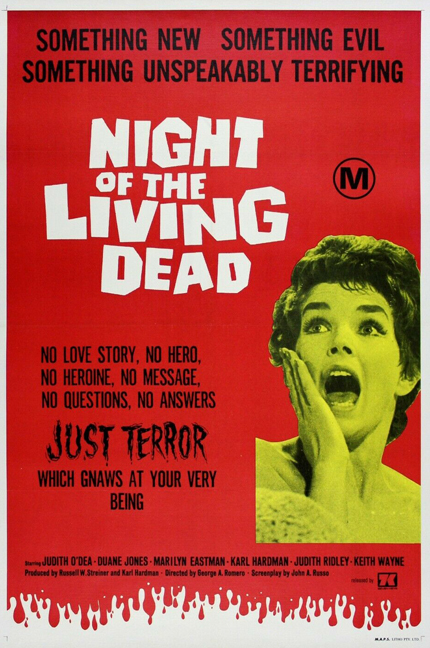

I started to meet people who had a similar mindset to me – that is, they were interested in not only the underground film scene but also in making commercial movies. There was a lot of film activity and creativity in Pittsburgh at that time. George Romero was at college there, and he was making Night of the Living Dead (1968).

I was becoming disenchanted with academia, so I took the Bolex camera home, and I started making my own films with it. After I got my master’s degree, I was invited to join a film production company being formed by some friends from Pittsburgh and Washington D.C.: they were starting to do political advertising for the candidates in the capital.

Were you political as a person or were you just a filmmaker at that stage?

This was the 1960s so I guess everyone was political. At that stage, I wasn’t a radical one way or the other, but I was definitely aware of what was going on in the world – and I was dead set against the war in Vietnam.

Did you take any filmmaking courses?

No, I was completely self-taught. I didn’t have any formal film experience, but I took the job and became a production manager for some big-budget political commercials. This was the big league. It was for senators and governors. Basically, that was film school for me, because I was learning how to shoot and edit the whole thing.

I was working in Washington and traveled between there and Pittsburgh. I got married to my first wife, and we had a son. The commuting was difficult so we were deciding whether to move to Washington or not.

At the same time, we visited San Francisco. I had a few contacts out here; I knew some people that were working with Francis Ford Coppola. He was just starting American Zoetrope at that time. I liked what I saw so I decided to move to San Francisco, and I got involved with a number people from Zoetrope.

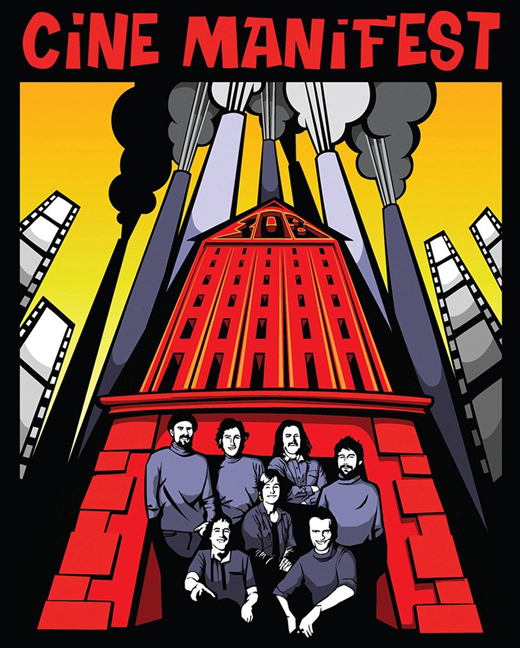

We wound up forming a collective to do left-wing political advertising, called Cine Manifest.

It was a small group of Marxists/communists who got together in the early 1970s, We wanted to match idealism with activism to change the world for the better. A lot of members of that group eventually wound up making some great American independent films. Rob Nilsson, for example, who was part of that group, has gone on to make quite a name for himself. He’s won awards at Cannes, Sundance, you name it.

*

2. Adult Film Origins

When did you come across the adult film business?

The film scene in San Francisco in 1970 was going in different directions, and one of those directions was adult movies – even though there was still no real adult industry then. Alex de Renzy was doing a few things, and the Mitchell Brothers were getting going, but it was early days. What I remember most was that if you made a porno feature film, the rest of the film guys in town would view it as just an independent feature film. It happened to have explicit sex in it, but there wasn’t a large distinction from other films.

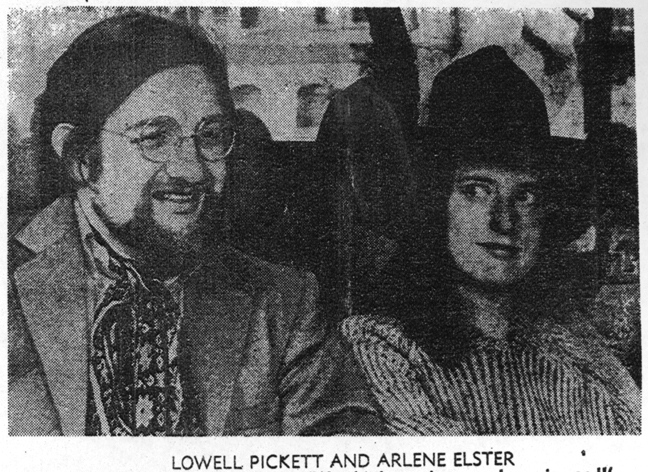

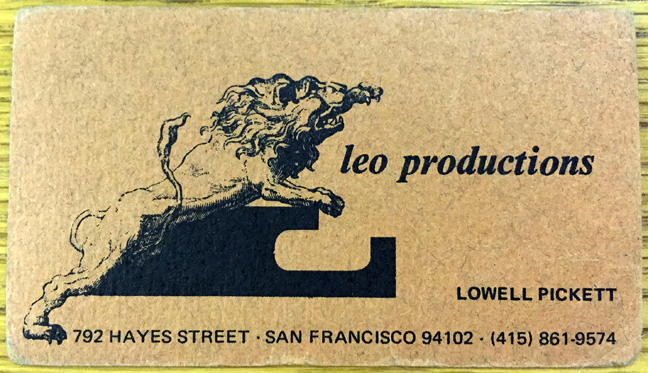

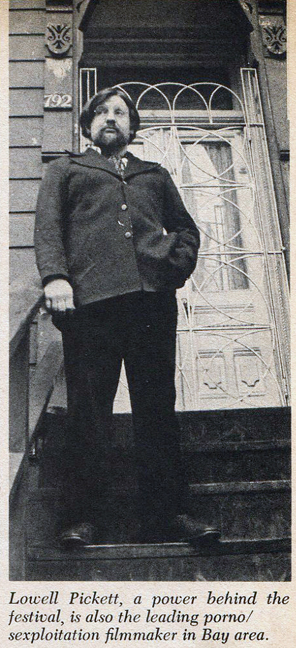

It was at that time I started a dual career in the adult film scene. When I’d worked in a lab in Washington, I’d seen an ad for an erotic film festival organized by Lowell Pickett and Arlene Elster.

I’d been interested in erotica for a long time. So when I moved to San Francisco, I bought a copy of the Berkeley Barb, which was the paper where Lowell advertised for people to be in films. He also advertised for people to direct sex films, so I replied to the ad. That’s how I met Lowell. I sat down with him, he explained how it worked, and I made a couple of short films for him. He was doing loops at the time. He liked what I did, so we took it from there.

The combination of radical political films and making porn must have been quite a combination…

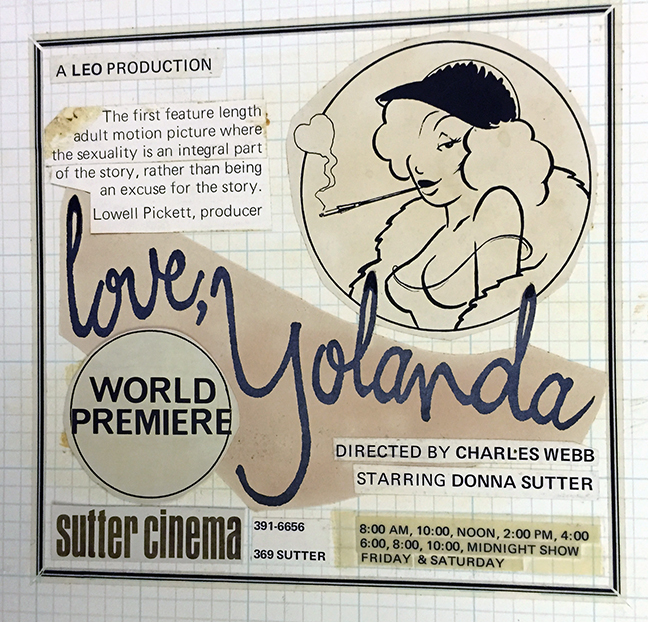

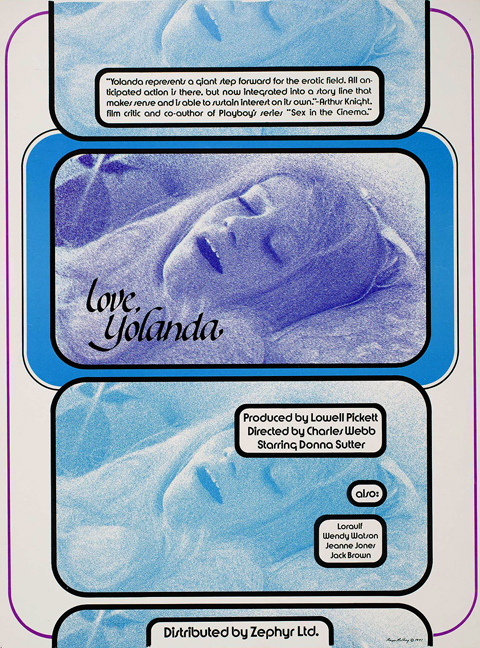

Yes. For example, I made two significant films in 1971. One was Love, Yolanda which I made for Lowell, and the other was George Jackson: The Death of a Revolutionary, about the Black Panther revolutionary that was co-produced by Granada TV in England. I was the director of photography for that.

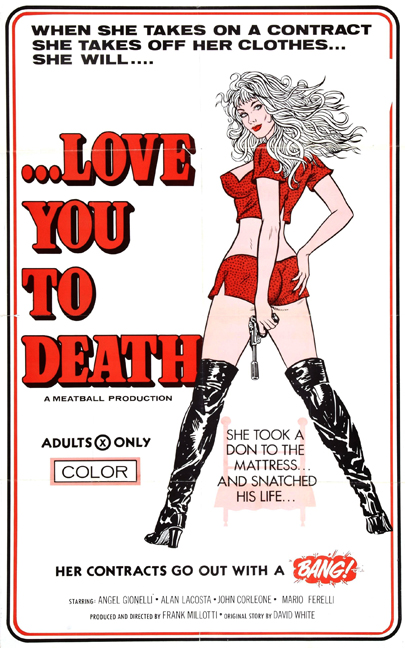

Original ad layout for ‘Love, Yolanda’

Original ad layout for ‘Love, Yolanda’

Looking back on it, it may seem that my career was headed in two separate directions, but in reality, it all was happening at the same time in San Francisco. It was a very vibrant film scene.

What was your first impression of Lowell when you went to see him? I guess you went to his house on Hayes Street?

Yeah, I did. Lowell was an eccentric, and he was part of the Beat Generation in San Francisco. He used to work at the Art Institute, and hang around North Beach, which was where the San Francisco version of the Beat Generation was based. Places like the Co-Existence Bagel Shop. I looked at him as a wild man, but he was also this vortex of activity and energy. He was always at the center of everything.

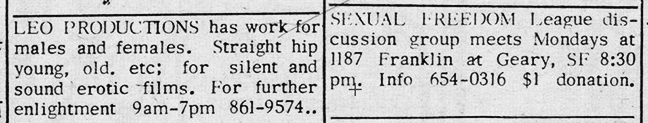

And there was a whole thing going on at Lowell’s house on Hayes. That was the world headquarters of Leo Productions, his filmmaking company. Lowell and his whole group were also involved with the Sexual Freedom League, which was just starting out at that time, and with the Sex Institute, which is still going on.

What do you remember about Leo Productions?

Lowell had a group of filmmakers who were working with him, many of whom were film graduates from San Francisco State. They considered themselves serious filmmakers, not just people doing porn, but Lowell gave them this chance to actually make their own movies. He had a good production crew, people that were well-trained and serious about this. They knew what the heck they were doing as far as making movies went. It’s not like now, where everybody who’s got a smartphone is a porno producer.

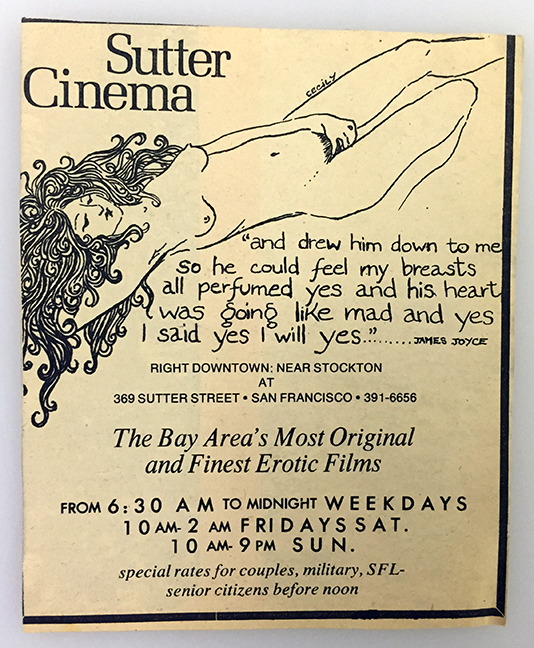

Lowell was a crazy character, but he got things done. He’d have premiere parties at the Sutter Cinema whenever they released a new film. Those parties were key social events in San Francisco at the time. I met all sorts of people there. Guys like Herb Gold, the Beat novelist who hung out with William Burroughs in Paris. These writers or painters would wind up at the premiere parties. To be on that list was a very hip thing for socialites, for creative types, and for people who just wanted to go watch a dirty movie.

So there wasn’t a time where you thought to yourself, “Hey, if I get too involved in this porn scene, it might stop me from doing the political documentaries”?

I thought of that, and I kept the two separate. But like I said, at the time, the adult films were an organic development out of what was going on in society. People that were involved in the adult side of my work knew about the documentary part, and vice versa. There were a number of people involved in left-wing political causes that were doing X-rated films. It was all part of the counter-cultural scene. Plus, there were a lot of left-wing hippie chicks that were starring in these films. Then they got married and settled into obscurity and nobody would ever hear of them again.

The whole scene was cool. It didn’t feel like a covert or secret double life.

What do you remember about your first feature film ‘Love, Yolanda’?

I directed it, and I shot it in 16mm. Lowell produced it. It was a big success. It played at the Sutter for months and months and months and months.

The star was this hippie girl. Lowell gave her a whole fake back-story saying that she was from a historical, rich San Francisco family connected to the Gold Rush. It was a promotional thing that Lowell came up with to boost the film.

I used some music from Ravi Shankar that I didn’t have the rights to. Of course, everybody was using whatever music they wanted – and getting away with it because the films were so underground that it would barely get noticed. As it turned out, Ravi Shankar actually went and saw the film because he liked X-rated, explicit sex films. And apparently, he liked the use of the music. He never bothered us about it, which is kind of cool.

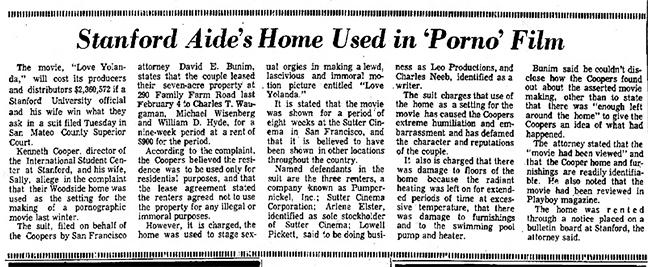

I know that ‘Love Yolanda’ caused a scandal at the time.

Yes, but not because it was sex film. We shot parts of it in a mansion down in Palo Alto. Lowell got a signed release from the people who lived there. But it turned out they were a group of guys that were just leasing the house through the summer. Technically they didn’t have the rights to sublet the house for this kind of purpose. Months later I got a knock on my door early in the morning and I got served with a million-dollar lawsuit. Lowell got served with the same lawsuit.

It turned out that the house was owned by a dean at Stanford University and that some friends of his had gone to see the film. They saw this guy’s house in the middle of this sex film. So… here comes this lawsuit. I got an attorney and basically the whole thing was dropped after a while. It was basically a shakedown because the film was doing so well. The guy reckoned that we were made of cash and wanted a piece of the action.

So you suddenly had a lot of publicity?

I’ll say. There were articles in the newspapers that this guy who had been doing political advertising in Washington was now making explicit films. It was all just hooplah around promoting the film. The whole hardcore feature thing was brand new at that time. Lowell was competing with the Mitchell brothers and the O’Farrell Theater, and so he loved the media scandal. He was just trying to get attention. And it worked.

What do you remember about the other people involved in Lowell’s film collective?

We all worked under the Leo Productions banner, and there were a number of talented people who worked there.

Steve Howe was one. He really was a talented filmmaker. He was Lowell’s production manager, and was also a brilliant film editor. He was not really involved in the X-rated industry much after the early years. He headed off and became a world traveler. There was another director who went on to work in local TV named Bob Klein. Mark Hofherr was a sound guy. Peter Breeze was a regular director; he was an independent filmmaker and he had a sound studio. He had a mixing studio set up in his garage in Marin County. Then there was George Paul Csicsery, who worked regularly with Lowell. He’s still around, over in Berkeley, and has become is a well-known documentary filmmaker. George has distanced himself from the sex films, but he was in it up to his neck. I guess he has a reputation to protect but he was thoroughly involved in the scene for a period of time there.

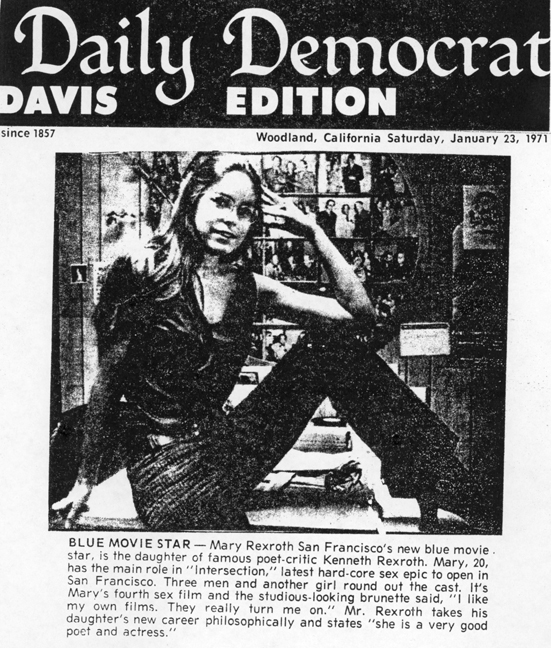

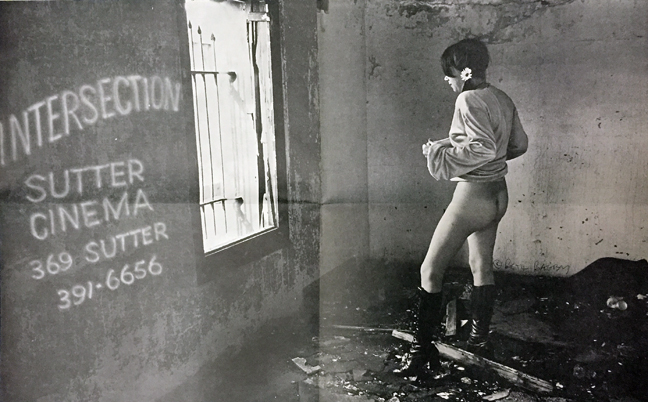

I remember a film called Intersection, which was directed by Jann Burner and starred Mary Rexroth whose father was the well-known Beat Generation poet, Kenneth Rexroth. So it was all quite incestuous.

What do you remember about your next film, Aphrodisiac (1972)?

I made that film with Lowell. It was about a piece of fruit that was injected with an aphrodisiac. When people ate it, sexual escapades ensued… Aphrodisiac was a cute little film. It was pretty good for its day in terms of production values.

Where did the funding for Leo Productions movies come from?

Lowell had a business partner – a guy we called ‘Aaron Linn.’ He’s listed as the producer on a lot of these movies. That’s a pseudonym. His real name is Arthur Chang. He had a lot of regular business interests – he was the head of the Monterey Urban Renewal Agency for example – and he wanted to protect his identity and fly under the radar.

Arthur did some of the distribution through Zephyr Distribution. He had contacts with folks in New York. I think he sold ‘Aphrodisiac’ outright – to the Perainos who had made Deep Throat.

I was not really involved with the movie after I shot it for him. I shot it and cut it, but I was not involved with anything beyond that. As soon as I heard the Perainos were involved, I was happy to move on and have nothing to do with it.

Excerpt from The Rialto Report interview with Lowell Pickett:

After ‘Deep Throat’ came out in 1972, the mob thought that every film could become another ‘Deep Throat’ and they could make all kinds of money. I had just released a new film. It was a film which featured an orange that was injected with an aphrodisiac. So all these people had some of this aphrodisiac. That’s basically the plot of it. We made that film twice – once with Charles DeSantos as director.

Then I got a call from somebody who said that the guys behind ‘Deep Throat’ wanted to distribute this film for me. I knew that that would be a disaster because I wouldn’t see any money. Stan (Borden) had already told me what happened to the people who made ‘Deep Throat.’ He told me not to get involved with them.

I ended up suggesting that I’d sell them the film for $100,000. They flew me to the Bahamas where their contact man was, named DeFlavio I think. We ended up haggling back and forth. Finally they gave me $75,000 cash. They told me how to put it into a Bahamas bank and then how to get it back into the United States in a month. They told me to bring it back to the States in amounts under $10,000 so as not to arouse suspicions.

I had a guy with me named Arthur Chang. We were partners for a short while and he had some experience with finance. He figured that $10,000 would fit in our pockets. So we carried $9,500 each on our flights back. We did that a few times until we got the money out of there.

I don’t know what happened to that film. I never heard anything about it after that.

Does Lowell’s version sound accurate to you?

That sounds about right, although truth be told… who the heck knows? I was not there. I was not in on the distribution of that film. So I don’t know. But it sounds like, from what I know about it, that’s approximately what happened.

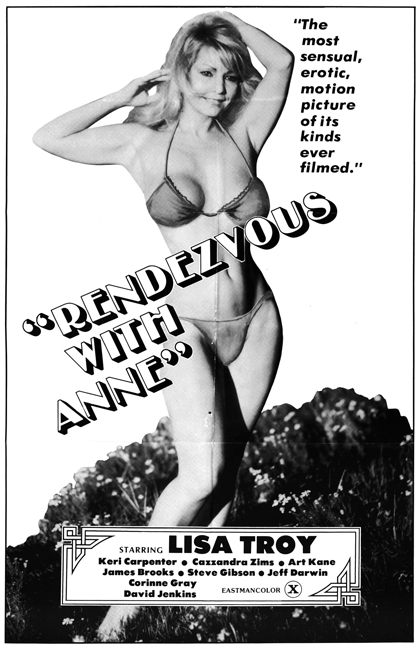

The money they got from ‘Aphrodisiac,’ they used that money to make Rendezvous With Anne (1976).

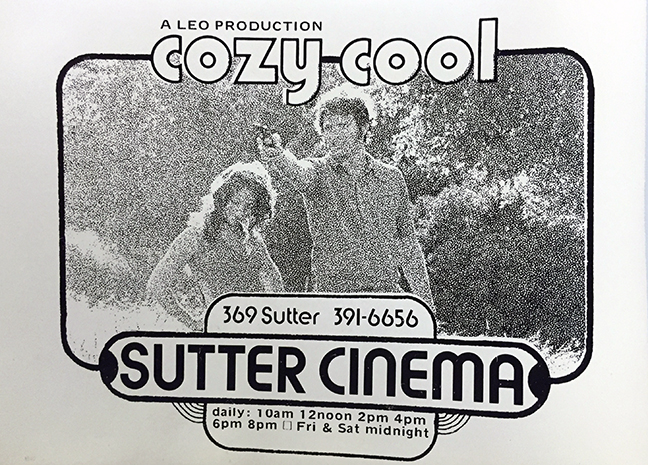

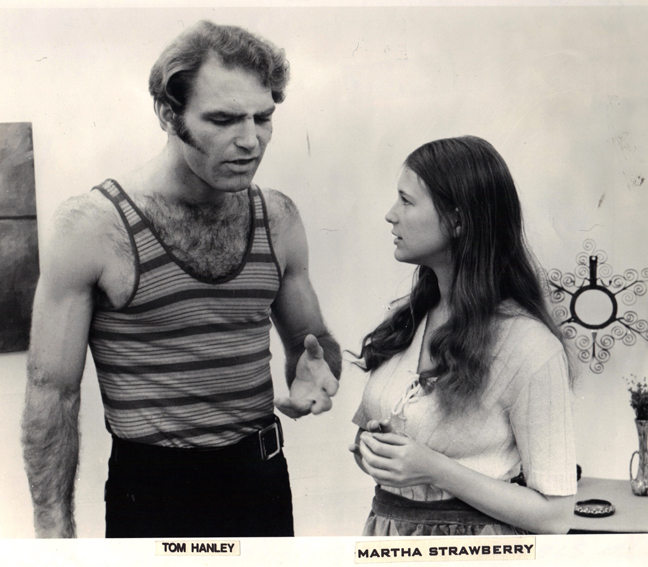

One of Leo Productions biggest films was Cozy Cool. What do you remember about working on it?

The guy that directed ‘Cozy Cool’, was named Dustin Holmquist. I haven’t had any kind of contact with him since the mid ’70s. I do believe that’s the only movie he did. He was connected with the Stanford Film Department.

It was one of the higher budget films that Lowell did, but it was such a mess. Maybe everyone was trying to be a little bit too ambitious. It was supposedly a gangster film, and I know Lowell was trying to bridge the gap between hardcore and B-movies so he could get a different kind of distribution deal. He should have stuck with what he knew best. The film didn’t turn out like he wanted. Dustin directed it and I shot most of it, but the production went on and on, and for a time it seemed it would never get finished. Eventually I did a salvage job on it, some re-editing, and some fill-in shooting. It was re-cut several times, and it came out with different titles, like ‘Love You to Death.’

Which actors do you remember from the very early days?

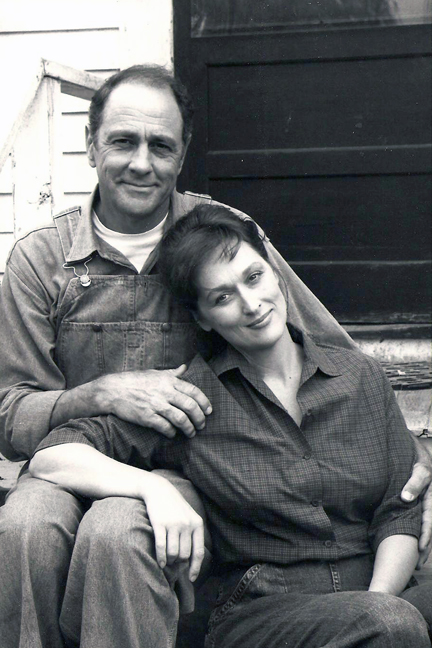

Jim Haynie was one of the leads on Cozy Cool. He became a Hollywood character actor, but he started out acting in sex films with Lowell Pickett. Jim’s one of those guys who’s always on TV today. He’s in everything. Lowell always liked him because he reckoned Jim was reliable sexually and he was a good guy to have around.

George McDonald, I remember working with him all that time. He was working with the Mitchell brothers a lot.

As for the women, Lowell was advertising in the Berkeley Barb and other places, and a lot of times the women that were in his films would come rolling through. They’d be in one film or in a couple of loops, and then they’d move on down the line. They weren’t really interested in developing into hardcore actresses. That came later.

But it was different with the guys. They stayed around longer, though they were harder to find. It was difficult trying to find people who were reliable, guys who could get it up consistently. That’s why Ken Scudder was successful, he was good at that. So was Jim Haynie and so was George McDonald.

Another guy that Lowell started was a makeup man, David Clark. David was the most fabulous makeup man that ever worked in the adult business. David worked on all of Lowell’s films, and Lowell gave him the opportunity to do experimental stuff. David went on to have a conventional career in television and the movies too. He made up everybody from Marilyn Chambers and John Holmes to Barbra Streisand and the Pope.

*

3. Marxist Politics and Mainstream Moviemaking

After the first few X-rated credits in the early 1970s, on films like ‘Love, Yolanda’ and ‘Cozy Cool’, the next time that you have credits with regularity is around 1976, and then they become quite more frequent. During those intervening years, what were you doing?

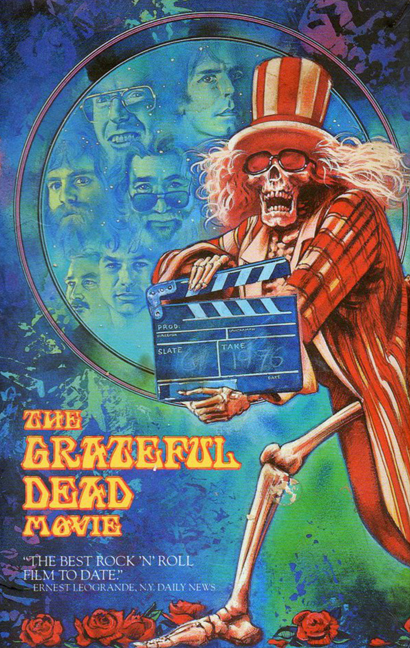

I was always helping out on early porn productions, but I was also working on mainstream stuff, such as The Grateful Dead (1977). That was a concert movie about their show at the Winterland in San Francisco in October 1974. It was one of the biggest concert films ever made. We had hundreds of technicians, and sound and lighting guys on that. I was the production manager. That took a lot of my time.

But my main activity during that period was political. I took a turn and became more active with the Cine Manifest group that I’d worked with for a few years.

Cine Manifest had a film production service called Manifest Production Services, and we had a group truck with all the film stuff that you needed… cameras, lights, a 35mm editing suite, all that sort of thing. We were one-stop-shop filming for people that were doing major TV ad campaigns.

How did the film production relate to the political goals of Cine Manifest?

We shot TV commercials like, say, Miller Beer commercials or Buick commercials, and our group used the proceeds to make political statement films that would increase awareness of left-wing causes and issues.

We made a couple of films before Cine Manifest gradually dissolved. But nearly all the group stayed in the movie industry in one way or another.

How did you get back into the adult film business from making political films?

I’d kept in touch with people in the adult business like Lowell, and I saw there were some interesting things happening. X-rated films were now being made with bigger budgets and better production values, and having big success in theaters. It seemed like an interesting thing for me to pursue again.

*

4. Return to XXX

When did you move into X-rated films full-time?

I got back into shooting X-rated stuff in late 1975 but none of the films came out until ’76 or ’77. In fact, the times that I look back most fondly on in my life are the mid ’70s up through 1982. After that, video changed everything.

During the mid-to-late 1970s, more and more movies were being made, and it was like X-rated film-making was mimicking Hollywood with strong production values, a star system, Adult Academy Awards, and all that kind of stuff. In fact, it seemed similar to what I read about Hollywood being like in its inception in 1910, 1915. That period seemed really similar to what was going on in the adult industry in the late 1970s.

When I got really active in the adult world, there wasn’t time to do a lot of mainstream films. And most of that production was in San Francisco and New York, and not so much in L.A. You can’t really say everything went to shit when video came in, but it just really changed the whole dynamic.

When you returned to making adult films, after having made mainstream and political movies, did you find that you had improved as a filmmaker?

Yes, I did, because adult films allowed you to take chances that you couldn’t take in other areas of the film business. They weren’t just extreme stories with explicit sex. It was about finding new ways of shooting, or trying out different lighting.

There were two groups of people making adult films. Firstly, there were the people who came from a film-making background, and then got into the adult, which describes my situation.

Then there was a second group of people who had never made a regular film and didn’t have any desire to make a movie, but who wanted to make money. They just learned how to use a camera, and used adult films to get into the production and distribution side of the industry. I’m not saying they made bad films, but they weren’t coming from the same place that I was. I looked at X-rated films as low-budget experimental movies.

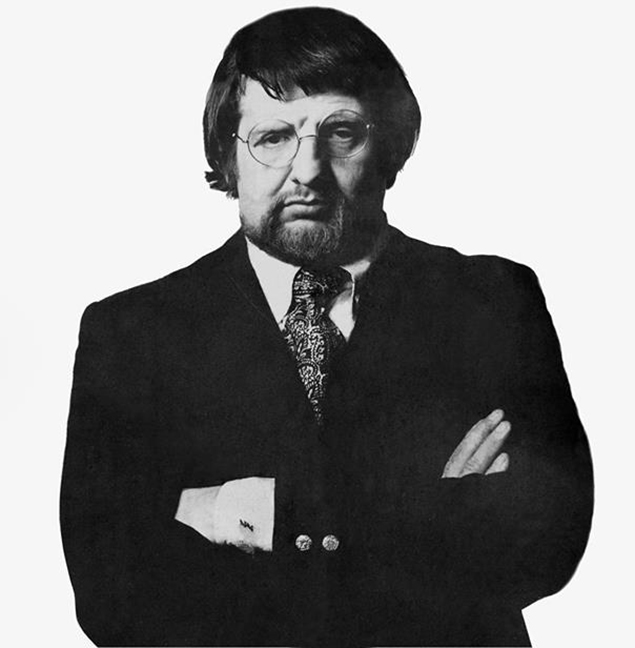

When you came back into the industry, you started using different names, such as Charles DeSantos and Chuck Angel.

Yes. I partnered up with a couple of people and formed a production company called Candid Image. I wanted to come up with a name to put on my films that had a certain ring to it. Alex de Renzy was well known at the time, and his name sounded foreign. And then you had Radley Metzger on the east coast who became ‘Henry Paris’, so I wanted to come up with a name that sounded vaguely European and arty. We were just goofing around, and I came up with ‘Charles DeSantos’ and decided to stick with that.

There were a couple of variations on the name – such as ‘Charles De Santi’, where the credits got screwed up and I just left it that way. I think that happened on Extreme Close-Up. By the time we found out, it was too late. We were dealing with film not video. It was so expensive to correct it that we just said, “To hell with it.” But I became Charles DeSantos.

As for ‘Chuck Angel’, that doesn’t sound like anything except an exploitation filmmaker!

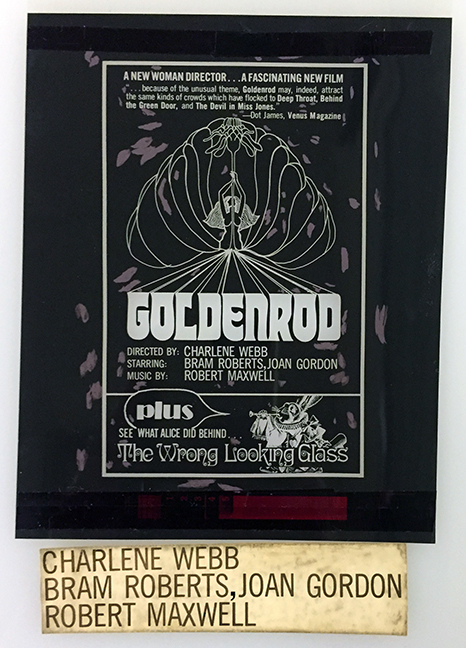

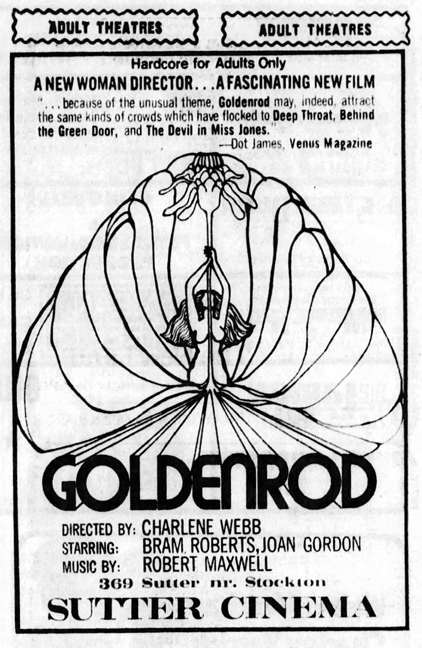

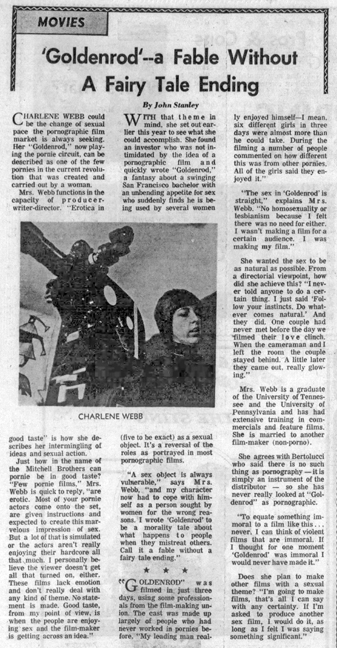

Who was Charlene Webb? I noticed that credit on a few films in the early years – including a film called Goldenrod (1976).

Charlene was my first wife. She was originally from Atlanta, and she was working in the Hollywood film industry as a script supervisor at that time. She was just getting into it.

Back in those days, there was a lot of talk about women getting into explicit films and making feminist porn. It was the first time the feminist movement had thought about this. So we decided to make a film from a woman’s perspective, and she directed it and actually used her own name. It turned into quite a thing. It was shot in 16 mm, and it had a feminist angle to it. We called it ‘Goldenrod.’

Original ad layout for ‘Goldenrod’

Original ad layout for ‘Goldenrod’

Can you remember the plot?

Charlene played this secretary in the opening scene of the film. Her boss comes in and puts the make on her and insults her in a chauvinistic way. Then the boss, who is this Casanova type, goes with his girlfriend, and he finds he has a problem: he’s got a hard-on that won’t go away. Throughout the film, he goes through one scene after another trying to satisfy himself with various combinations of sexual partners. Finally it dawns on him what’s going wrong: he calls his secretary and apologizes to her, and you watch as his cock starts to droop and his hard-on goes away after he says sorry. It was a great scene.

It was a feature length film but it didn’t follow the usual tropes of an X-rated movie. It didn’t even have a cum shot in it. The guy that played the lead character was really talented. He didn’t really do much of anything else in the industry but he should have, because he was good sexually. It was a difficult film for the male lead to shoot but he pulled it off okay.

‘Goldenrod’ wasn’t widely distributed. We lost control of the film because in those days, if you let a 16mm print out of your immediate control, you didn’t know what the heck was happening to it. We did show the film at the Sutter, as a matter of fact, in San Francisco. But after that it just disappeared.

Did you get any publicity for the fact that you were trying to make a feminist porn film?

There was a big article in the San Francisco Chronicle about Charlene when the film came out. It had photographs of her, and focused on her being a feminist hardcore film director.

After that film, we parted ways and she moved back Atlanta and had a career working on feature films and commercials. The adult films were not something that she pursued after ‘Goldenrod.’

*

5. Industrializing the XXX process

When you returned to making X-rated films, where did the financing come from?

My main financier in the Candid Image company was Arthur Chang. Arthur had been involved with Lowell, until they had a falling out over a variety of different things. So Arthur came to me and said, “Let’s put something together.”

Arthur and I wound up making quite a few films together, but he always preferred to stay in the background. We were all trying to stay under the radar at that point. We weren’t like the Mitchel Brothers. We weren’t out there beating the drum. We wanted to play it close to the chest and not really get a lot of publicity. Arthur was always publicity shy. That’s why we called him ‘Aaron Linn.’ His real name never ended up on the credits of a film.

What was the business model for your Candid Image company?

The X-rated market was changing. Arthur knew of people that were selling 16mm prints all over the country. What they did was to shoot a film in 16mm and then travel across the country themselves and sell the prints to different territories. For example, you could go and sell New York, and you could sell Seattle, and you’d get enough money from selling different prints to make a nice profit

There was a guy named John Bicknell who was one of the guys that sold prints all over the country. You probably haven’t heard of him. He was a shady, underground character, but there were several of these guys that distributed in this way, and they would travel across the United States with a bunch of prints under their arm, selling them, and then the prints would show in 16mm theaters. This was before the golden age of porn, where films were being shot in 35mm and distributed more or less like regular films.

Apparently, Arthur and Lowell had decided to do a string of these 16mm films, but then they had the falling out. That’s when Arthur approached me about setting up a company together and making these films. That’s where the funding came from. The films were cheap, so Arthur financed them himself. It’s not like we had to go out and raise money from investors.

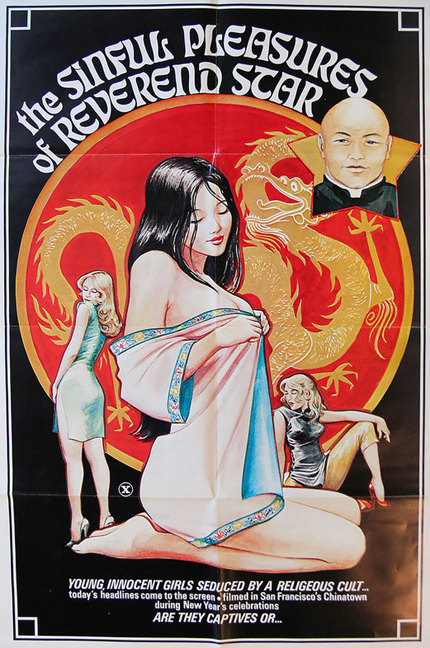

Sweet White Dream (1976) was one of those first 16mm films. Another one was called The Sinful Pleasures of Reverend Star (1977).

What was your biggest success in this period?

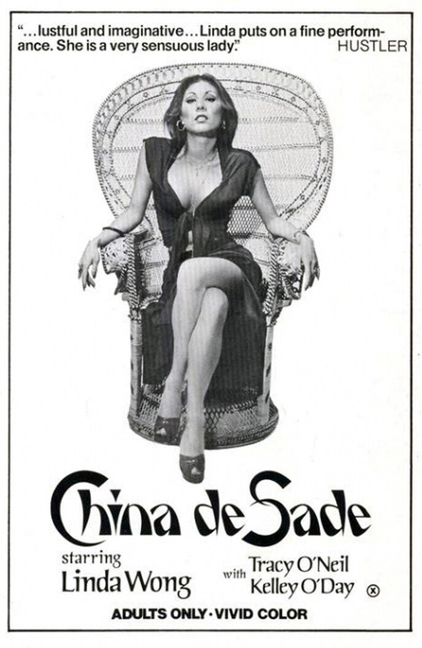

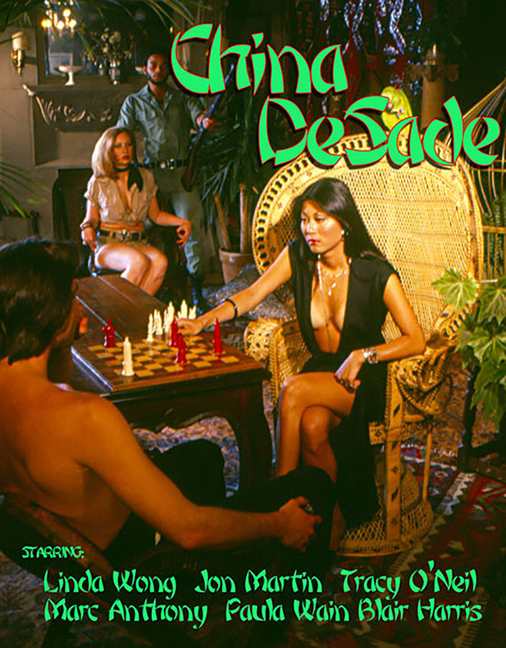

I shot China de Sade (1977) with Linda Wong, and we wound up making a deal with Mickey Zaffarano. He wanted the film to be a little bit longer, so I went and shot another scene and he blew it up. That really took off. That film was very, very successful.

‘China de Sade’ has some plot similarities with Apocalypse Now (1979) – even though your film came out three years before Francis Ford Coppola’s…

That’s an interesting story. The plot of ‘China de Sade’ consisted of a Chinese spy who falls into the company of a Colonel on assignment in Vietnam and then defects to the U.S. Basically the whole story is a take-off on ‘Apocalypse Now’. The only thing was that ‘Apocalypse Now’ was made a couple of years after ‘China de Sade.’ When ‘Apocalypse Now’ came out, a lot of people noticed the similarities, but they couldn’t work out how that was possible. They came to me saying “Your film has some scenes in it that were lifted right out of the script for ‘Apocalypse Now.’ Whoever made ‘China de Sade’ must have worked on ‘Apocalypse Now’ because some of the stuff is pretty much the same!”

Francis based ‘Apocalypse Now’ on ‘China de Sade.’ That’s my story and I’m sticking to it. (Laughs).

No, what really happened was, I was looking for a concept for a story in 1977. I wanted to shoot in an exotic location, an exotic type story, and I’d come across Linda Wong and the story of the Chinese spy. A friend of mine had an early draft of the ‘Apocalypse Now’ screenplay. It was making the rounds. Everybody in San Francisco read the thing long before it went into production. I read it, and then took the storyline and some of the scenes like the trip up the river, and added them to my script. That’s what inspired the story of ‘China de Sade.’

The film just resonated with people. We shot the whole thing in this big mansion in San Francisco. It’s not a great movie but it was a very successful film.

You had some mainstream actors in ‘China de Sade’ too.

Yes, Garry Goodrow and Larry Hankin. They were both well-known character actors in San Francisco. They were part of a comedy group called The Committee back in the ’60s that came out of Second City. It was like a precursor to Saturday Night Live. They were based in San Francisco, did improvisational comedy, and they were great actors. I put those guys in a bunch of these X-rated films. I had them doing dialog scenes.

What was Linda Wong like to work with? I’ve heard stories that later in life, she was unreliable. ‘China de Sade’ was at the beginning of her career.

She was consistently unreliable from the beginning! She was okay though. I had a good working relationship with her. She was one of these people that if you could get her to the set and in some kind of conscious condition, she was magnetic in front of the camera. You’d turn the camera on her and she had a magnetism. She wasn’t a great actress but she was very charismatic. She did well for us in that film and then she disappeared for a few years, then resurfaced later in the mid 1980s. When she came back, I put her in a little film that Ed De Priest distributed called The Erotic World of Linda Wong. That film had a whole host of problems that I don’t want to get into.

That was about eight years after ‘China de Sade.’ Linda was taking a lot of drugs by then. She died shortly after that.

Did you shoot more than one film simultaneously?

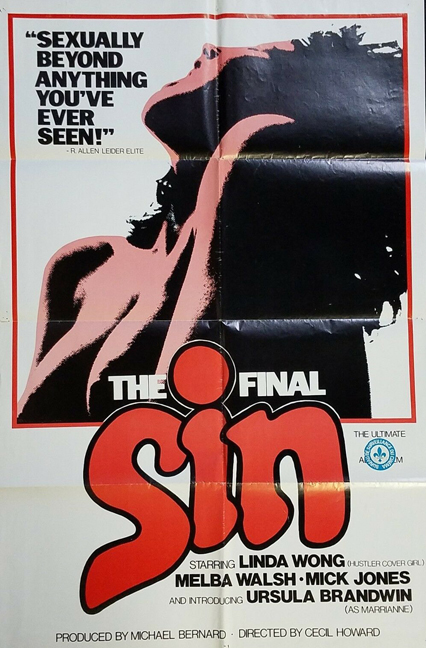

Yes, it was the best way to save money. Back in the mid 1970s, we’d shoot films at least two at a time. We shot another film at the same time as ‘China de Sade’ called The Final Sin, which also starred Linda Wong. We ended up selling it to Dave Darby outright in New York. It was later released on video, and credited to Cecil Howard, though he had nothing to do with it.

So your deal with Darby was different, in that you didn’t just sell him a print as you were doing with other films?

That’s right. But the concept of making films just to sell prints to different territories in the United States was short-lived for Arthur and I. Other people kept on doing it, but we saw that the industry was changing and developing in such a way that made it more like the mainstream film business.

It became more profitable to sell a film outright, so when we sold ‘The Final Sin’ to Dave Darby, we sold him the negative and the whole thing, lock, stock and barrel. He blew it up and distributed it himself. He could make his own prints for different territories. That’s the way it worked. The days of the salesman, basically carrying a suitcase full of films around the country, were finished for us.

*

6. Expanding the XXX model

Did your partnership with Arthur last long?

Yes, a few years. After ‘China de Sade’ we stopped making the 16mm films for print sales, and we started making films exclusively for theatrical distribution. The people Arthur was dealing with in New York, such as Stan Borden and Chelly Wilson, suggested we shoot in 35mm.

It was at that time that Arthur and I partnered up with Burt Steiger down in L.A. who owned a lab. After ‘China de Sade,’ we did The Liberation of Honeydoll Jones (1977) and Thoroughly Amorous Amy (1978). These films evolved out of that 16mm distribution model that we had going at the time.

‘Honeydoll Jones’ was shot in 3D. We shot it to be released with polarized glasses instead of red and green glasses, but we never released it that way because it was too expensive and it just wasn’t worth what it would cost to put it in the theaters that way.

Why did you shoot it in 3D?

Burt had a 3D camera set-up that he had developed for Roger Corman, because Roger was using his lab for some women-in-prison films. Roger wanted to do a 3D film, so Burt developed this 3D system for him.

‘Honeydoll Jones’ was one of the first adult films shot in 3D. There had been some others that were more cheaply produced, which were done with the red/green process, but since Burt owned the lab, he was in a position to do things economically that other people really couldn’t do. He produced quite a few films, not just adult films, over the years. He was the money behind some action films and horror movies. He was very active in Hollywood low-budget production at that time.

Apart from the 3D, what was Burt’s role in these films?

Burt was the producer. I wrote and directed them, and I shot them.

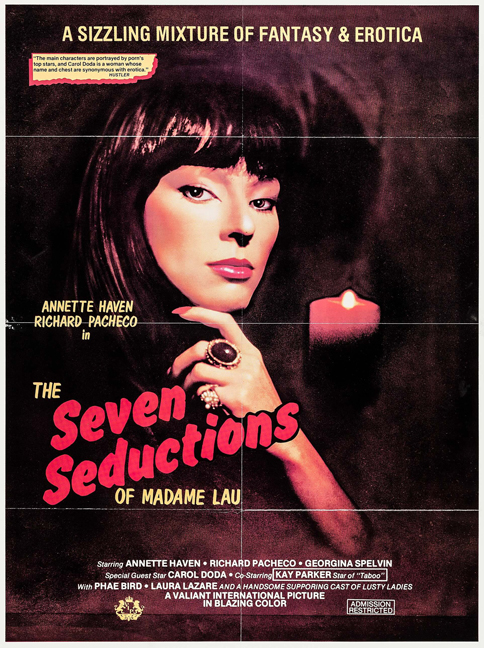

Burt and I were good friends by that point, and we did a bunch of stuff together, like The Seven Seductions (1981) and That’s My Daughter (1982). I made a lot of other films in the late 1970s, many of which I didn’t put my name on. My IMDb page is short by 12 or 15 films that aren’t on there.

I always focused on the filmmaking side. I had partners, like Burt Steiger or Arthur Chang, that handled the distribution. In Burt’s case, he was incredibly well connected in L.A. and so he was great at dealing with all the distributors, both theatrically when we were distributing 35mm and later when the business segued into video. Eventually he set up a video duplication capability in his lab, so he was dealing with all the people that were doing video too.

What size crew did you have, and did you tend to use the same people for most of those films?

When we kicked into gear in 1975, we were shooting all the time. Things were really happening fast, and we would go from one production to another. I put together a good, tight, professional film crew. A lot of these people worked in the mainstream film industry as well as in the X-rated industry. They’d work on commercials as grips or gaffers or sound people or still photographers. It made things function efficiently. Sometimes some of them would get busy doing commercials, which were paying better than I was, so I might have to find a replacement, but I worked with pretty much the same crew for long periods of time.

How about on the production management side, as that can save a lot of time and money on a low budget production?

True. I had some good people working with me consistently in that capacity. My sister in particular worked with me as a production manager. She was great on my productions. She eventually moved down to Hollywood with her husband to work as a script supervisor. I never moved down there. I’ve always been based in San Francisco.

Another person I worked with a lot was Kathryn Reed. She’d help with casting as well as some production and catering. Kathryn was Alex de Renzy’s first wife, and they’d worked together for years since the early days of the business. In fact, Kathryn continued to work in the industry through the ’80s, producing and shooting her own films, mostly gay films. She was helpful because she knew everybody. She was a treasure trove of contacts within the industry.

Later on, a really great production person who would always be the first person I’d call, was Tigr (aka Chelsea Manchester.)

Tigr and I worked together a lot: every time a new production came rolling along, I’d just call Tigr and we’d put the whole thing together easily and quickly. I’d have an idea by that time of what I wanted to do, in terms of story and cast and locations, and she’d just go and glue it together. Tigr was never really an actress, but she was great behind the camera and behind the scenes.

Tigr was together with Sharon Mitchell at that time. They were a powerful combination for many reasons. They had their problems like everybody else, but they were incredible when they were together.

How did you hire actors for the films?

When it came to actors, by the mid ’70s there was a little bit of a repertory company building up. I’d have auditions sometimes, but usually there was a group in the Bay Area, that consisted of people like Ken Scudder, Paul Thomas, Candida Royalle, John Seeman, John Leslie, Billy Dee, Don Fernando, Jon Martin, and Blair Harris. They were all friends and hung out together. Kathryn Reed was working as an actor’s agent so if we needed anyone else, she’d advertise for actors and help with the casting.

Harold Adler was another one of these guys that was doing casting. He was a still photographer, and also came out of the counterculture. He worked a lot with Lowell. Harold was doing big-time casting for film companies that came into San Francisco, and at the same time he was shooting loops. Lots of them. I always had a good relationship with him. In recent years, he started an art gallery and cultural center.

I was always interested in finding new people to appear in the films. The idea was you put two or three well-known people who had name value and reliability in a film, and then you tried to get at least one new face each time. That was ideal, if you could do that. But it wasn’t always easy. San Francisco was never heavily institutionalized for the film business. There was no agency for performers like there was in Los Angeles. It was a lot looser.

Some of the actors were helpful because they wanted to get into production, so you could use them as crew members too. I always had a good working relationship with John Leslie, and also with Paul Thomas. I knew from the get-go that PT wanted to direct. I first met him when we were doing ‘Sweet White Dream.’ He was watching like a hawk. He observed everything that was happening in terms of how we put that film together, and he said, “I’m going to make these films one day, and I’m just going to kick ass with it.”

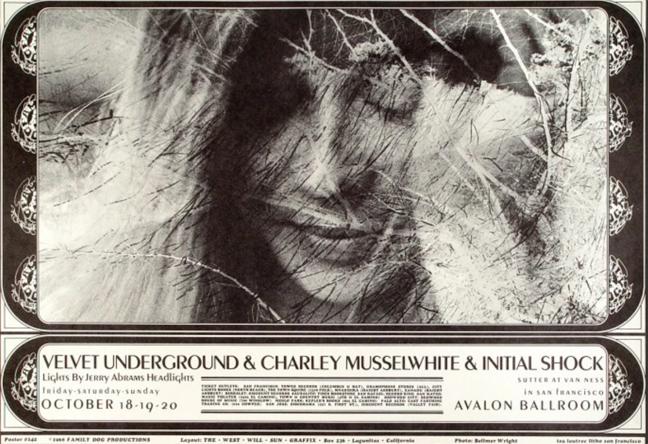

Did you ever come across Jerry Abrams? He was in the adult film scene in San Francisco from the very beginning, making some of the earliest loops and features.

Yeah, sure. I knew him for a long time. Jerry was another one of these interesting characters. He was known as ‘the Loop King.’ He was working with some people in Seattle and making one loop after another. He made hundreds of them.

Before that, Jerry was also very well known in San Francisco as a producer of light shows. He got a big reputation in the ’60s for creating light shows at rock concerts with the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, the Golden Gate Park and all that. He was another one of these guys that came out of the 1960s hippie counterculture. A lot of the San Francisco X-rated film scene came out of that group of people. Jerry was right in the middle of both parts of it.

He also had somewhat of a reputation for doing honest-to-God experimental films. I think that some of them were distributed by Canyon Cinema. There was one called ‘Sex Tune’ that was a brilliant movie. He was actually an amazing filmmaker, but then he really got bogged down in the sex loop thing and never really got past that. He always wanted to break into making his own features, but he never really did.

We worked together on a number of movies.

Did you stay in touch with him?

I lost contact with him over the years. I heard he put on a lot of weight. As far as I know, he never had a wife or anything. The last time I saw him was in the early 1990s, when he was driving a cab. I got into a cab one day. and there was Jerry. I said, “My God, man! What’s going on?” I reconnected with him then for a brief moment, but that was the last time I had any conversations with him.

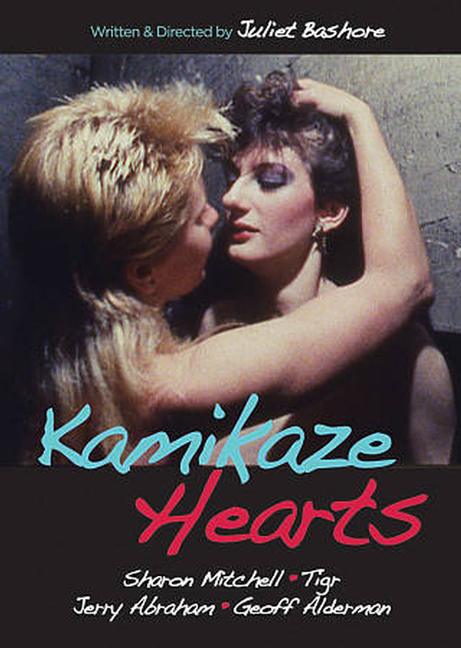

Jerry and I were both in a really off-the-wall, strange film called Kamikaze Hearts (1986). Walter Csicsery and David Clark, the makeup guy, were in that film too. That was a good reflection of what was going on in San Francisco at the time.

*

7. The Last of the XXX Films

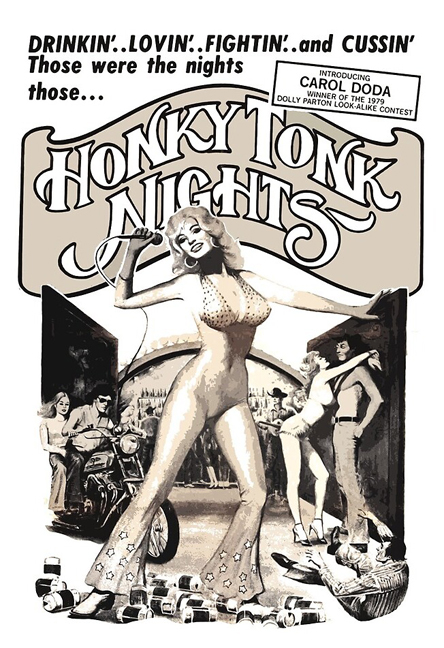

What do you remember about the film Honky Tonk Nights (1978), which looks like an attempt to produce a more mainstream film? The folk singer Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was in that.

That’s exactly right. Arthur and I came up with the idea. We’d had some great success with many of XXX films so we decided to make a crossover film. The idea was to do a hardcore version and an R-rated version of a film with a country and western theme.

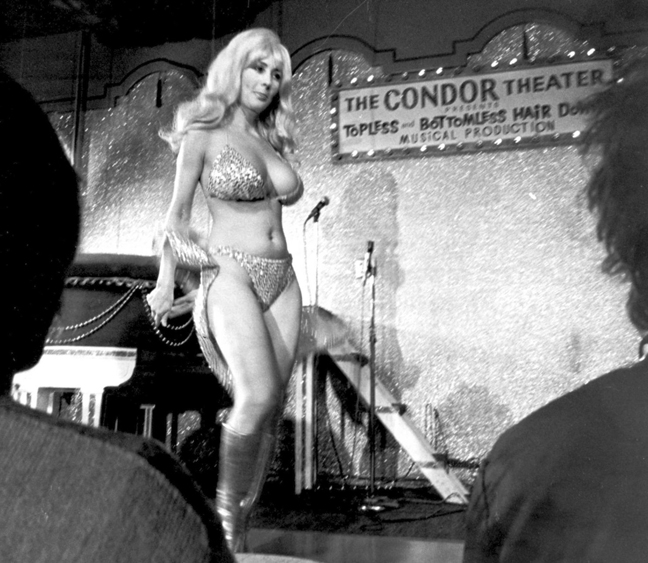

We got Carol Doda onboard, and she was a huge name in San Francisco. Most people outside of the city may not know who Carol was, but she was the first topless dancer in San Francisco in 1964. She danced at the Condor Club, and she had enlarged her breasts with silicone injections, which became known as the ‘New Twin Peaks of San Francisco.’ She’d always wanted to be a singer, so we cast her as a country singer in the film. She loved that.

It was a strange mix of people. Apart from Carol we got Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. I knew Jack because he wound up staying in our production office for several weeks. He’s another great character. It wasn’t difficult to persuade him to feature in the movie. Jim Haynie, who’d been the star of ‘Cozy Cool’ a few years earlier, and several other pornos since them, was in that movie too. Then we had adult regulars like Georgina Spelvin, Serena and Chris Cassidy. Just a whole mix of people.

The idea was to try to take it up a notch and see if we could get distribution outside of the adult industry. We had chase scenes and stunts and we had a great location. What we ended up getting was a complete mess. We talked about ‘Cozy Cool’ being a mess. This one was just the same. It seemed that when we tried to break out and make a better film, it didn’t turn out too well.

Even the weather was against us! We started shooting in September 1977, and it hadn’t rained in San Francisco for three years. It was a drought. We planned to do a lot a shooting outdoors, and then it started raining… It rained and it rained, and it rained us out. We had to stop and then re-start shooting again three months later. We lost some of the actors, so we had to hire people that looked like the original cast members. The whole thing was just turned upside down.

And it was shot in two versions?

Yes, we did duplicate scenes: one with hardcore sex; one with softcore. For example, we had a guy playing a country western singer that was the equivalent of Jack Elliot, and he would do the similar scenes but do them hardcore. We never finished that version, so it was never released. It was one of these strange films.

Did you ever hold onto any footage from the films you shot?

No. I wish that I had, because of the resurgence of interest in this whole period. I would write and direct and shoot the films and then everything, including all the stills, would go to the distributor.

I was working with a sub distributor here in San Francisco, Mike Weldon, who had the prints. Mike and I were close friends. He had a lot of my prints and others too – like Johnny Legend’s Teenage Cruisers. He had stills and posters too. He died of a heart attack at a young age, and I don’t know what happened to all of his archives. A lot of this stuff was held at whatever distribution organization was handling the movies, so we just lost track of it, to tell you the truth.

I don’t even have a collection of my old films on DVD or VHS.

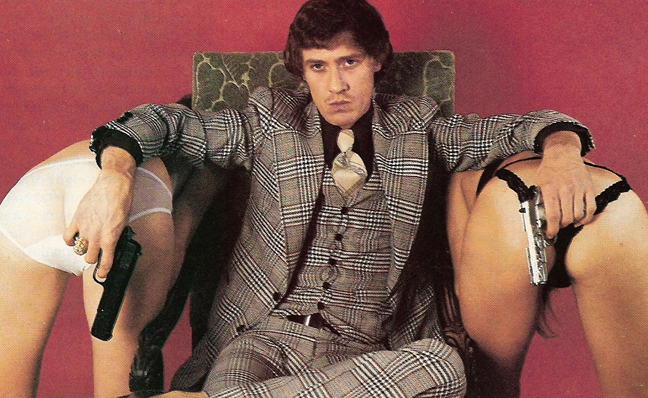

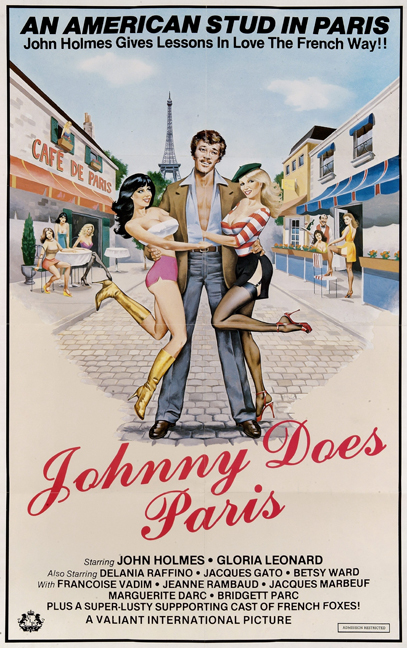

What do you remember about Extreme Close-Up (1979) and Johnny Does Paris (1981), which you shot in France?

My film production partners and I had an opportunity to go to France and do a couple movies, and so we put together the whole thing with John Holmes, Gloria Leonard, Rhonda Jo Petty, Jamie Gillis, and a few others. We decided to take some of the people from here, and then we’d find the rest of the cast and crew when we got over to France.

Before we left, we were in New York doing some casting and somebody introduced us to the Sloan twins. They’d been in some loops and small films. We were looking for some unusual people or unique things that would make our film stand out… so of course we were interested in them. They didn’t have a problem doing things like working with each other, so we took them over to France. They were interesting people: they came into the industry and then vanished after a while. I never really heard much of them after that.

What was John Holmes like to work with at that stage?

That was before his coke period, his drugs. I’m not saying he wasn’t using coke before he got into all that trouble with the murders, but it wasn’t a big problem for him then. Of course, I’d met him and knew him a little bit, but this was the first time I worked with him. To be honest, I found him delightful to work with. You hear a lot of strange stories about him, but he and I became good friends.

When we arrived in Paris, it was obvious that the French knew who John was. Some of the people on the French crew were connected with French movie magazines and so they wanted to interview him. Before you knew it, it was all over the French press that John Holmes was in Paris. He’d walk down the Champs-Élysées and people would recognize him, and come up to him to ask for his autograph. Of course, his ego was as big as his dick, so he got a kick out of it.

How different was it shooting in France from San Francisco?

Making an adult movie in France at that time was very different than over here, because the films were all officially registered in advance with the CNC, which was the National Centre for Cinema and the Moving Image. That’s an agency of the French Ministry of Culture that is responsible for film production in France. That was strange because it meant we were an ‘official’ film – unlike anything we’d done in San Francisco. We were out shooting on the streets of Paris with John Holmes, and we had police protection, traffic controllers and guards.

John got a kick out of that because he loved playing the movie star. He was a pack rat too. You had to watch him carefully when you went onto location because he always wanted to take a souvenir with him. We were in all these expensive locations and chateaus, and by the time he left to go back to the United States, he had this whole beer keg full of souvenirs that he had lifted from the various locations.

I worked closely with Gloria Leonard on the French films. She was very knowledgeable and mature about the whole process. She was much more than just somebody to be in the film: she was smart and responsible.

*

8. Move to Video

How did the industry change for you in the 1980s?

In a word: VHS. I made many more movies each year, because it was much easier and cheaper to shoot them. The market was flooded with all the product, and so margins dropped and it was more difficult to make money.

It was strange: because it wasn’t as difficult to make a film, you spent less time with people planning them and shooting them. So there were fewer friendships, and ultimately less fun.

Our moment had come and gone in the blink of an eye. We didn’t appreciate it until it was gone. And then it was too late. But it was great while it lasted.

*

Charles DeSantos died on August 3, 2019 in San Francisco, California.

*

I wait with baited breath each Sunday for the next installment….. AND YOU NEVER DISAPPOINT!

I hadn’t realize that Charles had passed………… very sad. Another pioneer is gone.

And to think that his stroy would have died with him if it were not for TheRialtoReport.

Excellent interview, and some unknown information revealed.

Did Johnny Does Paris ever come out on DVD? That film featured the late Desire Bastareaud He was a black dwarf who appeared in many French porn films in the late 70’s through 90’s. He was also in French Finishing School with Brooke West.

Forget about Six Degrees of Separation. As the Rialto Report has shown many times, porn and mainstream Hollywood were Two Degrees, or maybe One Pseudonym of Separation! Thanks!

The comedy troupe The Committee, in addition to Gary Goodrow and Larry Hankin, included Howard Hesseman, Rob Reiner, Peter “Jerry the Dentist” Bonerz, and many others.

Also hilarious that Jim Haynie, the dull, salt of the earth husband from “The Bridges of Madison County,” whom Clint Eastwood sweeps Meryl Streep away from, was a long-running 70s porno stud.

What a time and a place to have been alive. Great choice to leave us with DeSantos’s parting words: “Our moment had come and gone in the blink of an eye. We didn’t appreciate it until it was gone. And then it was too late. But it was great while it lasted.”

Did he ever incorporate his political views into his adult features?

Charles DeSantos really cool director x-rated film from the 70s my favorite iconic legend of all time John Holmes and Peter North that’s awesome article keep up the good work thank you and God bless

When I interviewed Gloria Leonard in Fall of 1987 for Issue #6 of the Exploitation Journal, she spoke quite fondly of Charles DeSantos. In the interview itself we mention him in passing, but off recorder she was very enamored of him. She also mentioned to us that Holmes was very ill, she said he had colon cancer. I liked DeSantos’s work…..

I remember reading an article “supposedly” written by Linda Wong in an adult magazine, the title of the article was I remember Johnny Wadd. There were a few pictures of Wong and Holmes together and she said that Holmes was dying of colon cancer. I guess that was the cover story about his illness?

What was ironic was that Linda Wong actually died a year before John Holmes did.

Great article. But one minor correction. Rhonda Jo Petty never went to France for Extreme Close-Up or Johnny Does Paris (unless it was purely in a behind the scenes context). She’s not in either film. I think Charles might have conflated Petty with Holly McCall who did go over.

Great Stuff! Wish we would get some more story about Mary Rexroth, knew her in the 70’s.

I also know Mary had a younger sister who dab in the business for a sec. her name was Katrina and she unfortunately passed away on New Year Eve in 1996.

This is a first in knowing that John Stanley,the author and former Creature Feature television show host who is regularly associated with horror films,action films,and vintage past films(from the 20s through the 70s) wrote an article(and an interview) for The San Francisco Chronicle on a porn filmmaker(since he strictly wasn’t interested in porn cinema]). Otherwise,another very informative and excellent article as always.

Thanks Steven!

Yet another 10/10 eye opening and information packed masterclass on the Golden Age! The biggie for me here was that Charles made “The Final Sin” which is right up there for me as being one of the best movies of the 70’s. Sad to hear he’s passed away but what a story. Bravo Rialto Report, all the best guys!