It all starts with a photograph.

A timeless, though long forgotten, picture taken in a police station.

It features a group of wildly disparate people bound together by a low-budget sex film made on a deserted island in New York City. Each of them were at a crossroads in their lives, and the decisions they made as a result of that day would affect them – and the sex film business – for years ahead.

It’s the story of an Oscar-winning film director, a small-time sex film actress with big dreams, a mobster who revolutionized the distribution of pornography, and a photographer whose career lasted over seven decades.

Who were these people? What were they doing in a police station? What was the nature of their offense? And who took their photograph?

It’s been fifty years and change, so what happened to each of them since that day?

The Rialto Report tracked down the people involved to hear their very different tales: a history that tells part of the story of adult film in New York.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Yesteryear

The Photograph

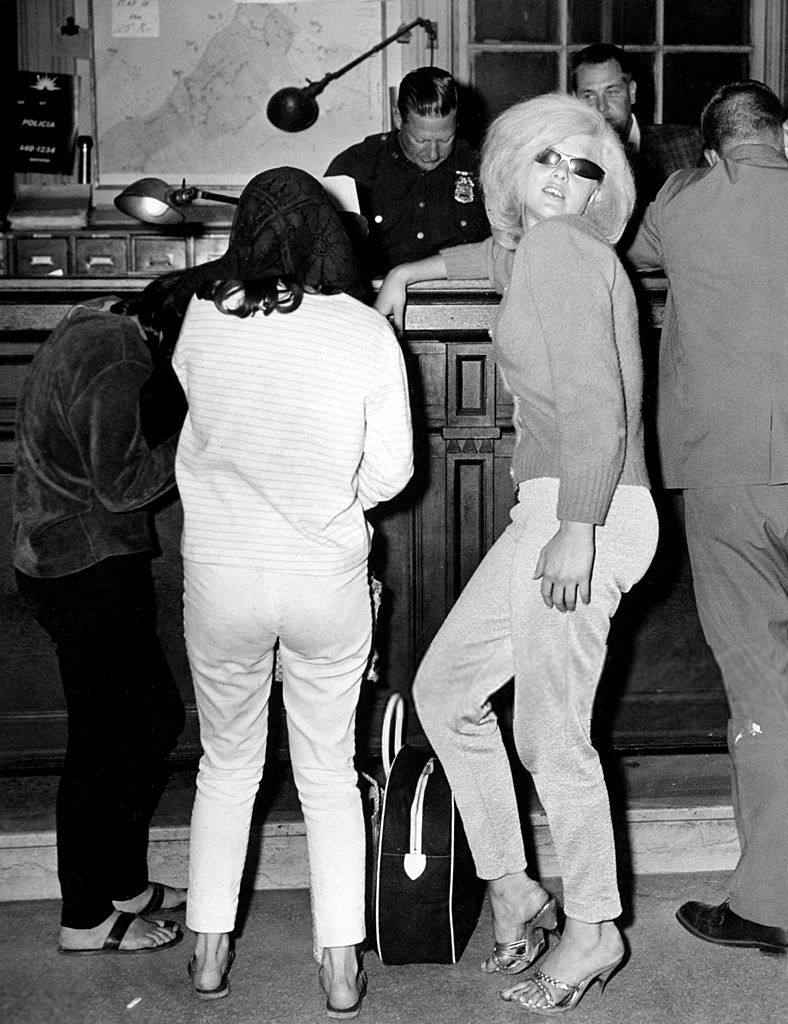

The image is in black and white. Of course it is: it’s a 1960s newspaper photograph, a long-forgotten snap taken for the New York Daily News.

The scene is the inside of a police station. Behind an elevated desk, a uniformed sergeant stands in front of a map of Staten Island. He looks down, suggesting that he’s working on paperwork relating to the people – three women and a man – who stand in front of him.

The man before the desk sergeant is on the periphery to the right hand side of the picture. He seems to be turning away from the other people. In fact, you wouldn’t know he was connected to the women unless you were told. And you probably also wouldn’t suspect that all four of them had been picked up for a sexual misdemeanor just an hour before.

Two of the women have their backs to the camera. They’re wearing plain flip flops, and are dressed in casual, loose-fitting clothes. Their heads are bowed and covered with headscarves. They huddle together, trying to merge into a single shape in a bid to become more anonymous.

But the third woman is a study in contrast. She wears tight pedal pushers, shiny sandals, and a platinum blonde bouffant that would shame Jayne Mansfield. But it’s her pose that ignites the tableau. She raises a shoulder, bends a knee, and fixes you in the eye. She dares you to ignore her, like a model who’s reached the top of the catwalk and is momentarily, finally, in the glare of attention.

But the rest of the world is taking no notice – except for the cameraman.

His job is to transform the ephemeral into the immortal. So he does.

The Photographer

Jim Romano was an old-school, first-on-the-scene, Staten Island news photographer with a sixth sense that drew him to the scene of a disaster like a hungry moth to a burning flame.

Take December 16, 1960, for example. Jim was buying rolls at the Buda Bakery when the shop assistant mentioned a report of a fire at nearby Miller Field. Jim raced out to his car and followed the sounds of fire engines until he reached the site of the tragedy. Two airplanes had just collided in mid-air, scattering 134 dead bodies into the clear winter sky. “I got a photo of the dead pilot in the cockpit with a cigarette still in his hand, and then got the hell out of there, real quick,” Jim remembers.

The tragedy at Miller Field, photographed by Jim Romano

The tragedy at Miller Field, photographed by Jim Romano

Jim’s success relied upon getting to a news scene in double quick time – preferably before anyone else showed up. So he pimped his car out with radios, all tuned to local police and fire department frequencies that provided him with a running commentary of Staten Island activity. Jim spent his days listening, and waiting, and listening. But when something happened, he was fast. He’d take off – and often beat authorities to the location. Sure, he’d likely be evicted from the scene soon after he arrived, but not before he’d taken some grisly photographs that recorded the mayhem.

Not all the events he rushed to were disasters though. In his time, Jim covered the visits of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra and John F. Kennedy. “I was interested in taking pictures of anything and everything,” he says.

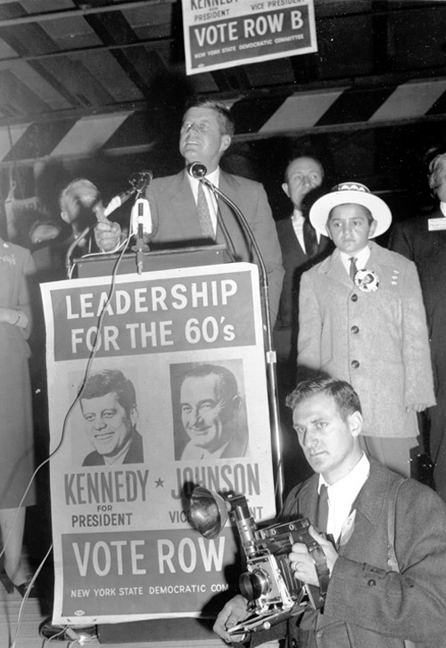

Jim Romano (with camera), and JFK

Jim Romano (with camera), and JFK

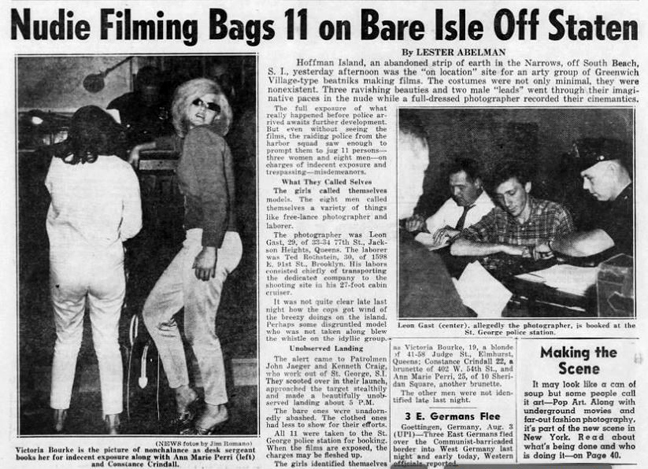

By the mid 1960s, he’d worked the island for twenty years and had seen most things, from births to deaths, and whatever happened to people in between. But late in the afternoon on August 3rd, 1965, he picked up a strange conversation on his police radio: eleven people had just been arrested on nearby Hoffman Island.

The charge? Mass indecent exposure and obscenity.

That was a first for Jim.

It wasn’t just the salacious charges that intrigued him. The location, a small tract of land in the Lower New York Bay off the south beach of Staten Island, was a place shrouded in local lore. Jim only knew what everyone else did about Hoffman Island: that during the late 1800s and early 1900s, it’d been a quarantine station where new immigrants were sent if they were diagnosed with a contagious disease. And that it’d subsequently fallen into disuse, a place that no one ever visited. It’d been in the news in 1961 when all the existing buildings on the island were razed. In the four years since then, Hoffman Island had cast a deserted, ghostly shadow.

The police radio chatter revealed that the arrested were being brought back to Staten Island by boat, and taken to the 120th Precinct station house in St George to be booked. But when Jim got there, most of those involved had already been released and disappeared into thin air. Only four people remained: three women who’d been apprehended in flagrante delicto, frolicking nude and maybe doing a whole lot more, and a man who was accused of filming them.

Jim never had the luxury of time. He knew that the only picture the newspapers wanted would be a snap of the wanton women. The problem was that two of them, the dark-haired Ann Marie Perri, 25, and Constance Crindall, 22, weren’t playing ball. They covered their faces, turned their backs to him, and refused to respond to his cat calls.

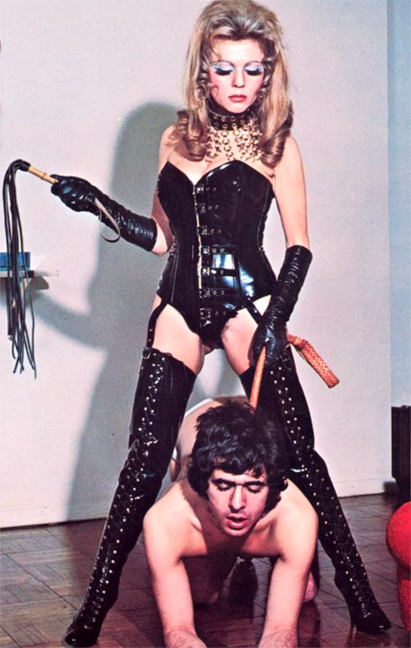

But there was hope. The youngest of the group, Victoria Bourke, 19, a glamorous blonde with wrap-around shades and high heels, seemed intrigued by Jim’s attention as if he was a paparazzo and she was a big shot movie star.

When a police officer spotted Jim and his camera, he ordered Jim to leave the precinct.

As Jim backed off, he called out towards the blonde: “Say lady: d’ya wanna be a star?”

Victoria spun around, tossed her head backwards, and pouted at the cameraman like a promiscuous Jackie O.

Jim’s camera clicked. The moment was preserved.

The Model

Rita Bennett was just relieved that she’d put her clothes back on by the time the two cops showed up on the island. She’d spent most of the morning nude, playing her part for the film, before taking advantage of the warm summer weather by retiring to a rocky beach to sunbathe.

The policemen still arrested her though. They cuffed her for just being part of the group on the island rather than for any immoral behavior. Rita felt bad for the other girls. After all, she was the ringleader who’d got them together for the day’s shoot.

At 24, Rita was one of the older women arrested that day. She’d grown up an only child on Long Island, only forty miles away from Manhattan, but a world away from the excitement she craved. As a kid she had few friends, and little affection for her parents, an old-fashioned couple trapped in the soulless prison of a loveless relationship. On a good day, her father was cold and distant. On a bad day, his temper was as sharp as a switchblade and almost as dangerous. Rita’s mother took the brunt of the physical abuse, which only increased Rita’s contempt for her: her Dad may have been a brute, but her mother was weak, spineless, and clearly lacked the courage to leave. Rita had no time for either of them. She felt neglected and forgotten, and she wanted out.

As she entered her teenage years, Rita suddenly became attractive and popular. She was smart enough to know the two were connected, so she devoted herself to curating her looks. She bought make-up, beauty treatments, and clothes. She paraded in front of the mirror for hours, modeling herself on Rita Hayworth and other sirens of the silver screen.

The payback was instant, as she became the object of men’s desires. Rita cared little for forming a lasting bond with any of her suitors – she was contemptuous of the idea of a suffocating full-time relationship – but she recognized what men could do for her. Men had power and money, and now she had something to offer in return.

Rita left home at 16 and moved into a room in a Manhattan apartment with five other girls she barely knew. She found work as a hostess in a bar, where her job was to engage men in flirtatious conversation so they’d stick around. She had to subtly persuade them to buy drinks at regular intervals, one for themselves and one for her. All the hostess’s drinks were supposed to be watered down, but Rita persuaded the bartenders to give her the real thing because she disliked diluted alcohol. The result was as predictable as it was messy: by the end of her shift each night, Rita was well done. The liquor numbed the pain of childhood, but left her unable to resist the unwanted advances of more persistent barflies who’d shove her into a taxi and take her to a cheap hotel room. The nights became a drunken blur, but that was OK. She preferred the details to be out of focus.

Shortly after Rita got work as a model. She smiled next to cars, restaurants, cigarettes, boats, and household goods. She paraded clothes, fancy jewelry and hats. The pictures appeared in newspapers, magazines, and on billboards. She became the face of an ad campaign for a Manhattan department store, which adorned the side of every midtown bus. Rita was proud of the work. She cut out every picture of herself, and glued them into a series of large scrapbooks that never left her bedroom.

Her recurring fear was that she would end up like her mother: wholly dependent on a violent man, popping pills to colorize a black and white existence. So Rita made hay while the sun shone. Her body became the product, and she sold it wherever she could. She worked as a topless dancer in clubs across the city, and posed for nude pictures in men’s magazines. The extra money meant she could pay for a place of her own, so she moved into a room at the Imperial Court Hotel on West 79th St. It was less glamorous than the name suggests, but she finally had what she wanted most: her independence.

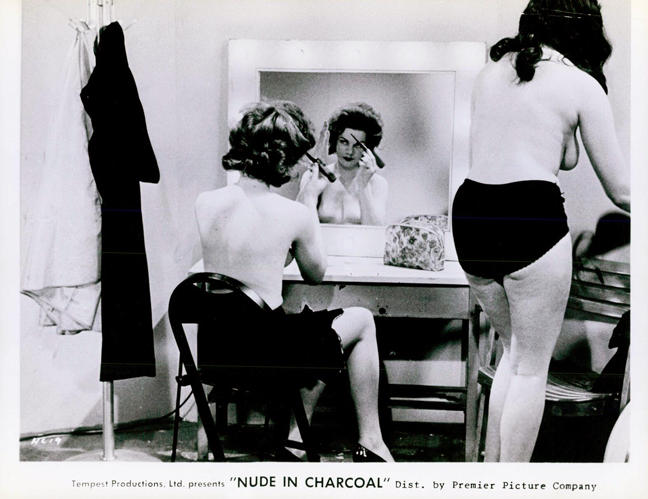

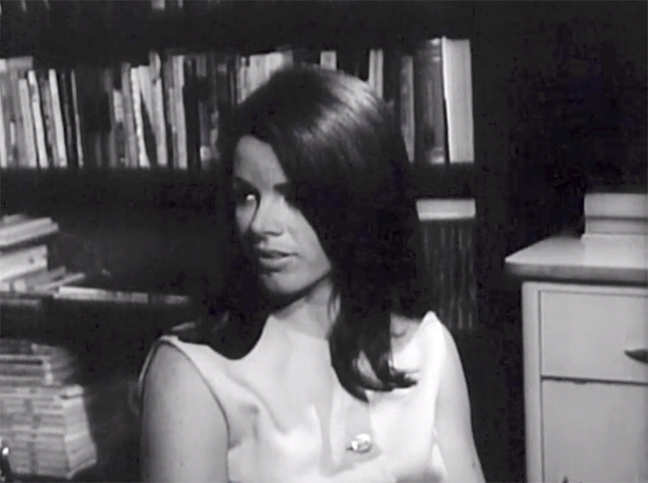

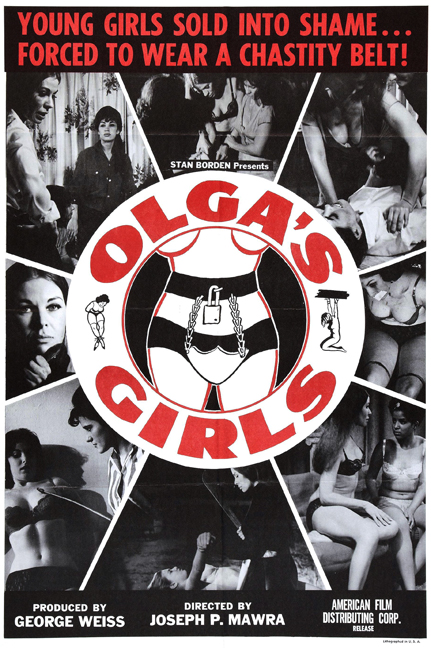

The stripping and nude modeling work opened other doors, though most of them had ‘Sex’ written on them. She turned tricks, and started to strut her stuff for primitive black and white adult films. Her first (unsuccessful) audition was for Radley Metzger who was hiring girls for sexy inserts to spice up Les Collégiennes, a French film he’d imported, and she took an uncredited bit-part in director Joe Sarno’s sexploitation debut, Nude in Charcoal (1961).

Rita, seated, in Joe Sarno’s ‘Nude in Charcoal’ (1961)

Rita, seated, in Joe Sarno’s ‘Nude in Charcoal’ (1961)

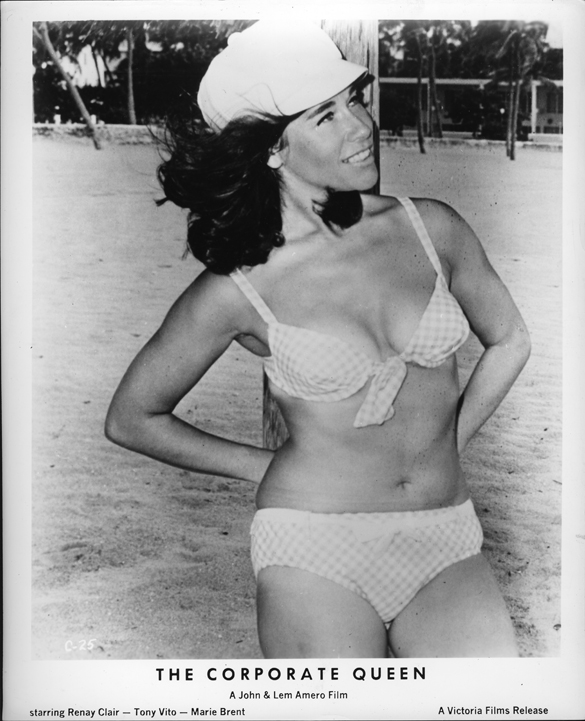

But it was a huckster called Barry Mahon who gave her regular appearances in film. Mahon, an ex-war hero and ex-manager of Errol Flynn, was re-inventing himself in New York as a nudie film producer. He went bananas when he saw Rita do the mashed potato one night at the Peppermint Lounge, and was sold. He smooth-talked her into appearing au naturel in his next nudie-short – but in truth, she needed little encouragement. Rita joined a repertory company of strippers and models, and in quick succession appeared in tame flesh operas such as Sin in the City and Crazy Wild and Crazy.

Rita can’t remember how she first heard about the job on Hoffman Island. It sounded fun though. A day in the sun, a boat trip, some modeling, and cash in hand by sundown. She recruited some friends from the stripping and modeling circuits, such as Dawn and Darlene Bennett (sisters, but no relation to Rita) and the Germanic, volcanic blonde Gigi Darlene. They all featured in the first segment filmed on Hoffman Island that day.

Rita also brought along Vicky Burke. Vicky was a New Jersey runaway who Rita had met at a hostess lounge. She was five years younger than Rita – which seemed like a lifetime at that age. Vicky was naïve and sweet, but wild and irresponsible too. She reminded Rita of the person she’d been when she left home. Everything Vicky did was to provoke people into noticing her. Her self-worth depended on attention. She dressed suggestively, drank to excess, and ran with a gangster crowd. But Rita could see through Vicky’s hard shell. Vicky was a good kid, and just needed some protection from herself.

So Rita found work for Vicky, such as the shoot on Hoffman Island. And it was Vicky whose suggestive shrieks during filming attracted the attention of two waterfront cops in a nearby boat.

The newspapers said that the policemen found Vicky ‘unadornedly abashed.’

The Film Director

Leon Gast was 29 when he was arrested on Hoffman Island.

He was an accidental pornographer, and never had any desire to spend his life making sex films. In fact, as a teenager, he didn’t have the grades or the motivation for any kind of career plan. But a cousin invited him to join a class on The History of Film at Columbia University, and the effect on Leon was instant: “It blew my fucking mind. I had that… ‘this is what I want to do’ moment.”

From that day, he consumed film as if he was playing catch up. His favorites were gritty, realistic, newsreel-style works like ‘Battleship Potemkin’ and ‘Paths of Glory.’ He enrolled at Columbia and took courses in documentary film and TV commercials.

For Leon the 1960s were all about getting filmmaking experience. If he’d been in Hollywood, it might have been easier, but in New York, his options were more limited. And ‘limited options’ usually meant working on industrials or sex films, so Leon did both.

He started working for advertising companies filming ‘table-tops’ – short interactions between, say, a couple of housewives, which present a product.

Leon explains: “Two women are having coffee.

One says: ‘Jane, you look a little uncomfortable, could it be hemorrhoids?’

‘Why, however did you know?’

‘Because I suffered myself until discovering Preparation H.’

The voice-over floats in: ‘Preparation H… in ointment or suppository form… brings instant relief to the afflicted area.’”

But Leon also had an eye for a good camera shot, and was soon engaged by fashion companies: “I started shooting hats for $7.50 a piece. Then corsets and bras, until eventually I’m shooting wedding dresses. That’s a much tougher gig, so I got more money for that.” His work appeared in Vogue, Esquire and Harper’s Bazaar.

And then there were the sex films. It was strictly ‘bra and panties’ work at that time, with nobody taking all their clothes off. Filmmaker Jack Bravman, who employed Leon, remembers, “For the girls, it was just about dropping your dress and acting sexy. Anything that resembled actual sex was purely accidental.”

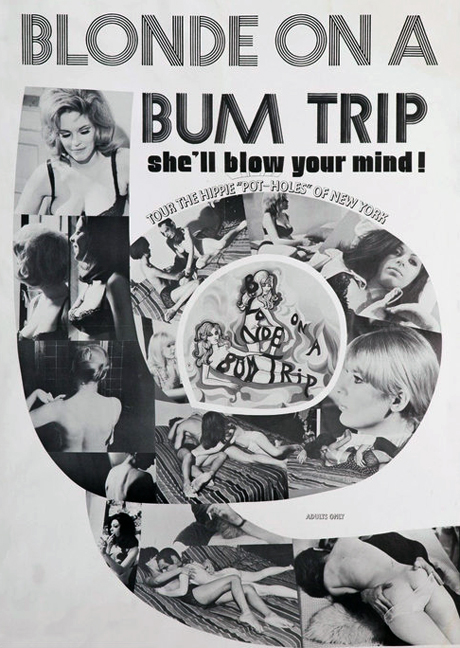

For Leon, it was plentiful work, easy to do, and brought in a much-need income stream. Along the way, he learned how to use Arriflex film cameras, Nagra sound recorders, and the rest. Nearly all of his involvement was below the radar and uncredited, so it didn’t jeopardize his mainstream work. Only once was his involvement in sex films formally noted, as cinematographer in the low budget but ambitious drugs-music-and-sex opus, Blonde on a Bum Trip.

But to call Leon the ‘film director’ for the Hoffman Island caper, as the newspapers did, is overstating his role. He’d been hired by a guy he’d met through a friend of a friend. The instructions were straightforward: he was the only cameraman – or crew member – involved, and his job was to shoot three set-ups over the course of the day. Each one was a cute vignette involving the actors – mostly women – disrobing. The only difference from the usual sex flick work that he did was that this job was taking place outside in bright sunshine, instead of in a small apartment bedroom.

It was late in the afternoon when the two patrolmen suddenly appeared in Leon’s shot. Somehow, they’d come onto the island unnoticed, and were now observing three women writhing on beach towels, their clothing long discarded. They were also watching Leon standing a few feet away, his lens trained on the naked flesh.

Leon had been caught red-handed and red-faced. The cops assumed Leon was the big fish. He was the one issuing the instructions so they figured he must be the boss, right? Leon protested his innocence. He described himself as a ‘freelance photographer’, strictly small cheese. He told them he had no idea what was going to happen to the film he was shooting. It was all true, but Leon was booked anyway, and named in all the newspaper reports. The film itself was confiscated by the police.

The Daily News loved the story, declaring that, “when the films are exposed, the charges may be fleshed up.”

The ‘Laborer’

The New York newspapers referred to the man at the side of the photo in the police station as a ‘laborer’. That was because he’d described himself that way to the cops.

The man insisted he was just an irrelevant guy from Brooklyn who had no idea what was going on. The Daily News believed his story, and reported that, “his labors just consisted of transporting the dedicated company to the shooting site in his 27-foot cabin cruiser.”

Theodore ‘Ted’ Rothstein wasn’t pleased that he’d been arrested, but he was happy with the way he was described. It wasn’t accurate, but at least it didn’t draw attention to his business. Any adverse publicity for his company would be the last straw right now.

The irony was that Ted was the brains behind the film shoot on Hoffman Island. The newspapers described the participants as a group of ‘Greenwich Village-type beatniks’, but they couldn’t have been more wrong. It was a professional operation by a budding pornographer.

Ted had set it up and paid everyone. He’d hired Leon to shoot it. He knew Rita from a girlie magazine shoot that he’d done. He asked her to pull together a group of actresses for the day. And it was Ted who was going to sell the Hoffman Island film to make some much-needed cash to keep his business afloat.

Ted owned a magazine distribution company, Star Distributors, that operated out of Brooklyn. It’d been incorporated back in 1948, specializing in niche trade publications. Initially it’d done reasonably well but suffered when richer national companies merged and squeezed Star to the margins.

Ted had taken over Star in the early 1960s looking to turn it around by finding new markets. He found one distributing risqué, softcore pinup magazines that the bigger companies were afraid to touch. It seemed a good idea on paper, but the sex business was influenced by the mob, and Ted’s Star Distributors found it difficult to gain a foothold. Star lost ground and lost money. Soon its operations were severely hampered by a shortage of cash. In the short term, the only way for it to stay in business was to change their payment terms: Star started asking publishers to pay them in cash in advance before they did any distributing. This broke the golden rule in the trade, where materials were taken on a consignment basis. Star became even less popular with its clients.

Ted tried branching out into producing his own publications – cheesecake pin-up magazines and nude photosets – but it was small beer, and it failed to stop the rot.

And then came the debacle on Hoffman Island. A court case loomed, with escalating costs and unwanted publicity. Ted kicked himself because he never had to be on Hoffman Island that day. But he was, and he was caught, and now he was paying the price.

It was Hoffman Island that convinced Ted that he needed to take more drastic action to save his company. Star didn’t just need a new plan. It needed new blood, a fresh vision, and a lot more money.

Step in a 28 year-old, smooth-talking Italian-American from Brooklyn named Robert, who called himself DiBe (pronounced DEE-BEE), an abbreviation of his surname, DiBernardo.

DiBe was a polished operator, a dapper dresser who preferred a mod cut to his stylish clothing. He wore tinted, aviator-style glasses, and his brown hair, although receding, was stylishly and regularly coiffed. On the surface, DiBe was a friendly, well-connected, and happily married family man with four kids. But he was also rumored to have organized crime connections: the word was that made his money in the wheel-alignment business with Gaetano ‘Corky’ Vastola, an ex-con and member of the DeCavalcante mob family.

DiBe approached Ted and made him an offer: Ted could stay on as the company president, but DiBe would became vice president and principal financier of Star. And DiBe would have the last word on any significant matter relating to the Star business.

Ted accepted. He had no choice.

DiBe’s first pronouncement was that Star would switch its focus: It would now deal in hardcore sexual material. It was time to get serious.

*

2. Since Yesteryear

The Photographer

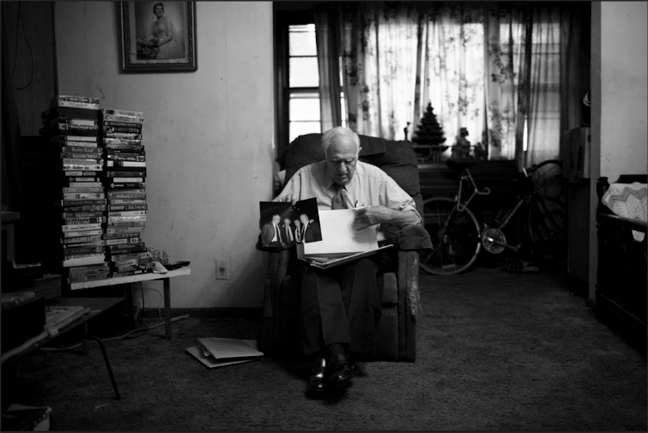

Jim Romano never left Staten Island. He’s 90 now, and still lives in the same house he shared with his wife until she died in 1979.

It’s been 73 years since the start of his colorful career shooting black and white images. In his own words, “I began with a one-dollar camera and a lot of personality.” He traded in that first camera and graduated to a 16mm folding model that he borrowed from his brother-in-law, before finally acquiring a hefty Speed Graphic, de rigueur for professional news photographers in that era. Nowadays he still takes photographs, though he uses a simple digital camera most of the time.

Jim was self-taught as a photographer: “Everybody has their own capabilities. Mine were stamina, patience, personality, and connections. That’s all there was to it.”

In the years since the Hoffman Island scandal, he continued taking pictures for all the New York newspapers. Predictably his archives burst at the seams with all of his photographs, but the one he still carries in his wallet is a close-up picture of JFK. He could “charm the birds out of the trees,” Jim says.

“But today you can’t do what I did back then. I could do whatever I wanted in those days. I made friends with police and firemen, and they often let me in. Today the restrictions on access are ridiculous… incredible. A working photographer like me isn’t allowed anywhere near the locations I went to. And that’s bad for the general public. They don’t get to see what is happening up close anymore. We’re desensitizing ourselves. We don’t know whats going on any more.”

The world may have changed since the afternoon he took the picture of the Hoffman Island arrests, but Jim’s reaction to it remains the same: “I don’t know what the hell to believe today – but if I see something… I still just photograph it.”

The Film Director

Leon Gast’s skill as a filmmaker was always matched by a keen ability to take advantage of any situation – crucial for success in the documentary film world that he aspired to join.

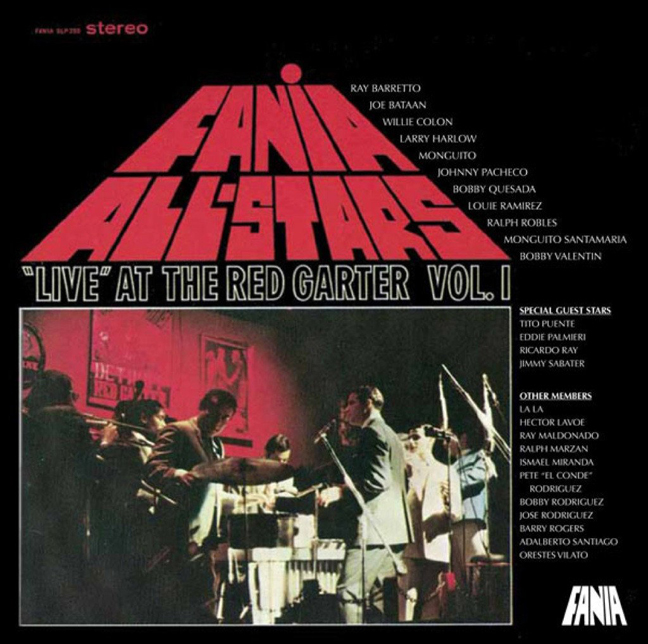

Take the first mainstream film he directed for example: Our Latin Thing / Nuestra Cosa (1972). In the six years after the events on Hoffman Island, Leon continued to shoot commercial photographs and the occasional softcore film: all were notable solely for their lack of success. Then in 1971, he was hired by Jerry Masucci – who owned Fania Records, a New York based Salsa record label – to shoot the cover for an album, The Fania All-Stars Live at The Red Garter. Other LP covers for Fania followed, so Leon suggested a film documentary that chronicled the birth of Salsa. It would center around an August 1971 concert at The Cheetah Club in midtown Manhattan, featuring Fania’s finest musicians, the cream of New York’s Latin scene. Masucci liked the idea, and gave him the green light. Leon’s film was a breakout success, finally putting him on the map as a filmmaker.

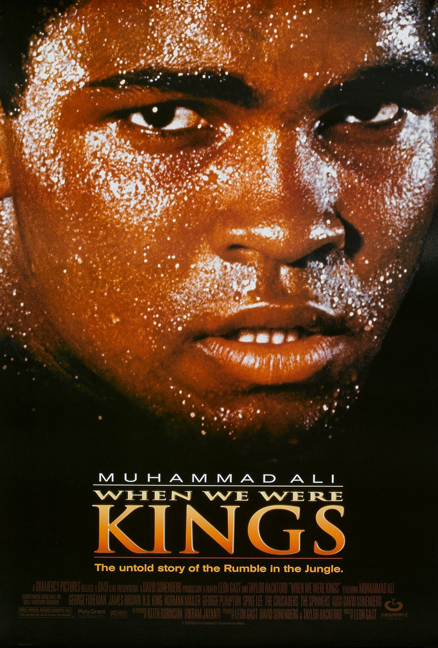

A couple of years later, Masucci again hired Leon. This time Masucci had teamed up with boxing promoter Don King to put together one of the biggest match-ups in history: the undefeated world heavyweight champion George Foreman fighting against the former champion, Muhammad Ali.

A three-night-long music festival to hype the fight was planned to take place in the days leading up to the big fight, on September 22–24, 1974. The festival would include performances by James Brown, B.B. King, Bill Withers, the Fania All-Stars, and many more.

The problem was that King and Masucci didn’t have the money – neither for the fight, nor for the concert.

Needing a large sum of money in a hurry is never a strong negotiating position, so when a solution was found it was unconventional and ethically-dubious: the whole event would take place in Zaire, sponsored by the country’s torture-and-murder-embracing dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, eager for the publicity such a high-profile event would bring him. And the proceeds from the concert would be used to make a lavish music documentary that would be released in theaters around the world. Masucci picked Leon as the man to make the movie, and so Leon left for Kinshasa.

But the best laid plans of mice and men (and Masucci and Mobutu) often go awry.

In this case, there were two setbacks. Firstly, Zaire’s despotic ruler declared that the music concert would be free-of-charge just days before it was supposed to happen. This was problematic given that Leon’s documentary was supposed to be funded from ticket sales.

And secondly, five days before the scheduled fight, Foreman acquired a bad cut above one of his eyes, and the fight was postponed for six weeks.

All of which meant Leon was stranded in central Africa.

So he turned his attention to the fight itself, and filmed Ali in the build-up to the big night. It proved to be a prescient decision: Ali, golden and God-like, was full of political bluster and bravado, preaching about the dignity of the native Africans and his hopes for African-Americans in the future. And when the fight took place, attended by 60,000 and dubbed ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’, it was a classic. Ali won by knockout, knocking out Foreman at the end of the eighth round.

When Gast returned from Kinshasa, he was broke – but he had 300,000 feet of unique and valuable footage. Over the next years, he paid the bills by making documentaries on the Grateful Dead and the Hell’s Angels. It wasn’t until fifteen years later, in 1989, that he found someone willing to invest $1 million to finish the Ali project. Even then, it took him a further six years to bring the film to the screen.

The resulting documentary was worth the wait. When We Were Kings (1996), was critically lauded and commercially successful. It went on to win the 1997 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and the Independent Spirit Award.

Gast himself was feted as being “a great chronicler of our times, a master of capturing the spontaneity of the moment.”

It was a far cry from a secret sex film on Hoffman Island.

Leon Gast (right), with Muhammad Ali and George Foreman

Leon Gast (right), with Muhammad Ali and George Foreman

The ‘Laborer’

Ted Rothstein quickly got over the Hoffman Island setback.

With hindsight, it’d been a watershed moment. He’d hit rock bottom, and the arrest forced him to seek external help for his business. With DiBe onboard, Star Distributors’ financial strength and credit rating improved dramatically. Cash flowed into the company, and Star went back to receiving merchandise on consignment. The business soon became one of the city’s largest wholesale outlets for pornographic magazines.

One of the most lucrative of Star’s clients was an explicit sex newspaper, founded in 1968, named Screw magazine. Screw was run by a couple of censorship-challenging upstarts, Al Goldstein and Jim Buckley, who freely admitted that their rag was distributed by a mob-controlled company like Star, but insisted they had no other options.

“When Screw was first published, distributors and operators of newsstands refused to handle the paper out of fear that they would be arrested on obscenity charges,” Buckley said. “It’s the law that forced us into Mafia distribution.”

Goldstein and Buckley signed a contract with Star, who agreed to handle the paper outside of New York – but not within the city. Law enforcement officials said that this was because Star and DiBe were linked to the De Cavalcante family which feared angering other Mafia families by encroaching on their local territory. (Distribution in New York City was handled by a different mob faction.) Nevertheless, the contract was lucrative for all sides, and Star flourished.

Another major source of revenue was on Star’s doorstep in Times Square. A multitude of new businesses trafficking in porn product had sprung up in an area where the police seemed incapable of preventing the flouting of obscenity laws. It provided Star with a lucrative and ready-made income stream, and their most notable outlet was Show World at 669 Eight Avenue, a self-described ‘supermarket of smut.’

Under DiBe and Ted’s guidance, Star became a multi-million dollar sex empire conglomerate, branching out nationwide, taking controlling interests in other sex-industry companies, expanding their scope to pornographic films, sexual devices, and dirty books, and controlling the bookstores, movie theaters, and publishing houses that they supplied. Star also formed relationships with other pornography magnates around the country such as Reuben Sturman. (Law enforcement was never clear whether DiBe and Ted were collaborating or extorting the people with whom they did business.)

If DiBe had created a new model for porn distribution, he was also a new kind of pornographer. DiBe didn’t hide his involvement in the sex business behind a middle man or a series of innocuous shell companies. He conducted his business openly. He drove between his suburban home on Long Island and Star’s downtown Manhattan offices at 150 Lafayette St in a 1972 Mercedes Benz with personalized number plates.

By the mid-1970s, DiBe’s mob connections were known to all. He was even caught by FBI bugs telling another pornography magnate, Michael Thevis, that ‘the family’ was in charge of all of his businesses. But DiBe was one of the very few thought to have become a ‘made man’ in the Mafia without committing a murder. In fact, he didn’t even have a reputation for violence and, unlike most Mafia members of his status, he didn’t retain a crew to back him up. Nevertheless, his Mafia links deterred potential competitors and warded off other criminals.

DiBe was seen as a phenomenal money maker, and described by a journalist in 1977 as “packing an unparalleled reputation as a tough-minded, competent, and shrewd businessman.” He cultivated a mainstream image as well, diversifying into investments such as automotive repair franchises, a car wash, pinball arcades, and several mainstream media distribution firms.

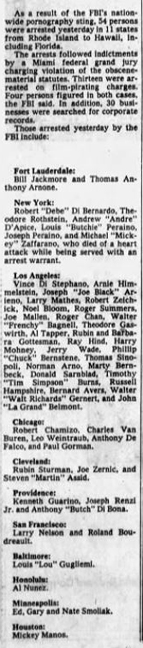

But Star’s high profile didn’t do DiBe or Ted any favors when the heat was turned up on obscenity prosecutions in the late 1970s. In 1980, a 2½ year undercover investigation by the FBI came to a conclusion. Based in Miami, and termed MIPORN, the operation aimed to crack the nationwide conspiracy controlling the multibillion-dollar pornography industry. DiBe and Ted were among the 45 people targeted, arrested, and charged with interstate transportation of obscene materials.

Newspaper article, listing the MIPORN arrests, including that of Robert DiBernardo and Ted Rothstein

Newspaper article, listing the MIPORN arrests, including that of Robert DiBernardo and Ted Rothstein

The investigation singled out four men it said were the country’s major traffickers in dirty books and movies: Rubin Sturman of Cleveland, Harry Mohney of Durand, Michigan, and Mickey Zaffarano and Robert (DiBe) DiBernardo, both described as organized crime figures from New York. The arrests meant that DiBe and Ted faced long jail sentences. Fortunately for them the case came crashing down when one of the two key witnesses, a dim-witted undercover agent called Pat Livingston, was arrested for trying to steal a sweater from a department store. DiBe’s attorney argued that Livingston’s crime was indicative of psychiatric problems that made it difficult for him to distinguish between his real identity and his undercover identity, and between truth and fiction. This made his testimony and actions highly unreliable.

Case dismissed, DiBe and Ted were free to go back to work.

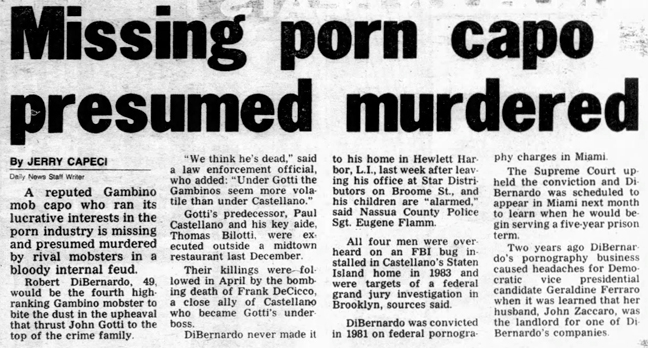

With hindsight however, DiBe probably wished that he’d been ordered to serve jailtime. Despite, or perhaps because of, his success over the previous two decades, DiBe had slowly become caught up in powerplay politics between John Gotti and mob underboss Sammy ‘The Bull’ Gravano. On the evening of June 5th 1986, DiBe left his office at Star to take his family out for the evening. He was told to stop off at the basement offices of Gravano’s drywall company on Stillwell Avenue in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. While there, DiBe was shot in the back of the head. His body was never found.

Robert DiBernardo, aka DiBe, is missing, presumed murdered

Robert DiBernardo, aka DiBe, is missing, presumed murdered

But the business that Ted had built, and DiBe had perfected, was too big to fail, and Star Distributors continued to be profitable even after DiBe’s disappearance. Ted moved the Star offices into a single 40,000-foot location at 20-40 Jay Street in Brooklyn, where he continued to start and acquire new businesses. By the 2000s, the company was divided into three additional parts: Bizarre Video, acquired from California which focused on adult films; Media Distributors, which distributed newspapers; and Novelties by Nasswalk which sold sex toys.

The flagship company, Star, concentrated on what it had done back almost half a century before – distributing magazines.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

The Model

I first met Rita Bennett in 2005, almost 40 years to the day after the events on Hoffman Island.

Unlike most actresses of the time, she only ever used her real name. I found her listed in the phone directory, living in an apartment just off Times Square on West 43rd St. She was happy to get together, and chose to meet in an old-fashioned steakhouse nearby. Age 64, she turned up in an immaculate white evening gown and an elegant large-brimmed, black and ivory hat. The overall impression was an aging Audrey Hepburn from ‘My Fair Lady.’ She spoke in a cultured, refined manner, and flirted gently. Clearly the teenage hostess from the 1950s had never left the building.

She remembered the day on Hoffman Island well. The arrest had been “unwelcome”, but the charges against her were dropped a few months later. She later had a relationship with a cop who went into the NYPD archives and got hold of the reels of film that Leon had shot. He gave them to Rita as an sign of his influence. Rita left the cop, but kept the film along with her scrapbooks.

Rita said that the Hoffman Island experience been a strange turning point for her. After that she felt a strange sense of empowerment: “I knew I was beautiful, but after Hoffman Island, I felt invincible too.”

Rita smiled: “But I was young then. And youth makes you feel stronger than you are.”

Rita, in Joe Sarno’s The Bed, And To Make It (1966)

Rita, in Joe Sarno’s The Bed, And To Make It (1966)

The new confidence made Rita want a career in movies. She continued to strip in clubs across the tri-state area, but now she got an acting agent and eagerly turned up at auditions for every big movie that was shooting in New York. She got parts in movies – some arthouse, some grindhouse – but drew the line at hardcore when sex films became more explicit in the 1970s: “I was a lady, after all.”

The good news was that Rita got roles in several major films: John and Mary (1969) with Dustin Hoffman and Mia Farrow, Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz (1979), and Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980). The bad news was that she was hired to play a stripper in each one. And then there was the harassment: producers wanted to get to know her more intimately, but wouldn’t consider her for anything that would break out of the stereotype she’d created.

Rita, in ‘John and Mary’ (1969)

Rita, in ‘John and Mary’ (1969)

By the mid-1980s, Rita stopped looking for film work, and stopped stripping too. “The world had changed too much. I was from a different era. No one seemed interested in anything I had to offer by then.”

She was still determinedly single (“I knew that a permanent man in my life would kill my spirit eventually”), so she found new passions: fashion and animal welfare. She didn’t stay in touch with anyone from the old days, but occasionally socialized with fellow characters from the day, such as Quentin Crisp and Taylor Mead.

I kept in touch with Rita after our first meeting, and saw her on and off for years. Sadly, the truth behind her glamorous façade was rather different. Her apartment wasn’t worthy of the name. She lived in a minuscule single room in an SRO building that she shared with a large dog, Buck. The building was overcrowded with poor, unwell, or mentally unstable residents, and Rita spent most of her time behind her carefully locked door in a room that hadn’t been cleaned in years. I joked that Quentin Crisp, who’d lived in a similarly messy space, always said that after four years an apartment doesn’t get any dirtier. “It’s just a matter of keeping your nerve,” he’d say. Rita just looked embarrassed.

But Rita’s problems were deeper than an untidy living space. She’d been an alcoholic for longer than she cared to remember. After our first few meetings, she either decided that she couldn’t, or couldn’t be bothered, to hide it. Years of good-time girl drinking in clubs and bars had taken a toll. Each time we met, she beseeched me to bring her a bottle of vodka, and a part of each of visit consisted of her throwing up in her postage stamp bathroom. To make matters worse, she’d been declared bankrupt the previous year.

Apart from Buck, she had one source of pride left: the scrapbooks that she’d kept since the 1950s. Lovingly curated volumes tracing her life through the films, commercials, and news events that she’d passed through. A chronological record of an eventful life that she was proud to share. She kept the books on top of her wardrobe with the Hoffman Island film reels.

Rita, in ‘Flying Acquaintances’ (1975)

Rita, in ‘Flying Acquaintances’ (1975)

I spoke to Rita in early 2017. She’d left the city and moved into an apartment block in the Hudson Valley, twenty miles north of Manhattan. She said she was happier there. It was a safer building, and Buck had more space to play, but she was keen to have visitors.

I called her a few weeks later to arrange a trip, but received no response. I tried again over the next months but with no more luck. Eventually I contacted the management company for the building in which she lived. They told me she’d died a few months before. She’d been buried in a potter’s field somewhere. No one seemed to know.

I asked about her possessions. What had happened to them, in particular her scrapbooks and the film reels?

The management company said she had no relatives, no next of kin, not even any friends who came forward to claim her personal effects when she passed. In situations like this, they said, the company can’t take responsibility for the deceased’s belongings. So they trashed it all. All of Rita’s belongings, recording her existence, were thrown away.

Rita, with Robert De Nero in ‘Raging Bull’ (1980)

Rita, with Robert De Nero in ‘Raging Bull’ (1980)

The Photograph

Today Jim Romano’s photograph taken in the Staten Island police station is long forgotten. The people in the photo are long forgotten. And Hoffman Island is pretty forgotten as well.

In the 1980s, the island was suggested as a place where some of the city’s homeless could be sheltered. Unsurprisingly the plan came to nothing. It’s currently managed by the National Park Service, and to protect the island’s endangered bird population, it’s strictly off limits to the public. The only visitors in recent years have been harbor seals observed wintering on the island.

The 1965 arrests are long forgotten too. In fact, it’s difficult to understand why a group of people could be arrested – and make the news – for something that thousands of people do on their iPhones every day.

But August 3rd, 1965 saw the brief collision of a handful of people. A local photographer, a hopeful actress, a budding filmmaker, and a failing businessman. They came together, made a sex film, got arrested, and never saw each other again.

If life is the sum of one’s choices, their lives were shaped by what happened that summer’s day.

*

Postscript

Vicky Bourke. Phone home. We’d love to hear from you.

*

Welcome Back Rialto Report!!!!!!!!

I’ve missed you, and I am excited about the upcoming articles and podcast.

Happy Sundays again………>!!!!!

We missed you all too S.d.!

Cracking story for your return from vacation.

I love the multi-layered account of how the different strata interacted to make or report on, the early sex films in the 60s.

As always you uncover stories that would be otherwise lost forever, and for that I am always grateful.

xxxxxxx

Thank you so much Hank!

GREAT story. How do uncover these stories?????

And please let us know if Vicky gets in touch.

Will do anon!

Have to admit, hearing about Rita Bennett’s passing was a hard one.

She was a favorite of mine so naturally I was fascinated to hear more details about her life. But I hate to think of her last days….

It is sad – we so wish she was still with us.

Welcome back, Rialto Report. Great story! One question: what happened to Buck the dog? I hope he found a home.

Sadly we don’t know Frank. Fingers crossed for Buck.

My God, you guys are awesome.

Thank you Larry!

As always, masterful writing and an amazing story.

Question: If Robert DiBernardo’s body was never found, how is it known he was shot in the back on the head.

Thank you JWP!

When Sammy Gravano flipped and testified against John Gotti he had to confess to every crime he had ever been involved with in order to get into the witness protection program. He was present when DiBi was murdered but another crew looked after disposing the body so he didn’t have those details. This is supposedly a common practice. Three can keep a secret if two are dead….

Thanks, brother!

Yeah, saw a talk-show where the

“routine” of “another crew” was

described. Invite, or bring the guy

over, and then immediately shoot

him as he walks in. Hang the body

upside-down from a shower-

faucet to drain the blood.

There’s some very impressive research and writing skills on display in this. The truth IS stranger than fiction! I’ve read a bunch of your stories and articles and Rita Bennett’s sad end isn’t atypical. It’s just that some endings are sadder than others . . . It is a shame her scrapbook and film reels were, well, scrapped. A treasure trove of interesting stuff was lost there. (Lil’ note: Under the screenshot of Rita Bennett from RAGING BULL it should read “Robert DeNiro” as opposed to “Robert De Neo”). I appreciate the hard work you do to track down these individuals and/or find out what happened to them (like ‘Navred Reef’/ Tom van der Feer).

Thank you so much F. Cold!

More amazing research. A forgotten photo from the past is the starting point and unravels a fascinating web of real history about the people involved, their dreams and motivations, the morals of society, law enforcement, organized crime. And then it gets personal and human. How very sad that Rita Bennett’s life closed the way it did, and those careful scrapbooks are in a landfill somewhere.

Bravo Rialto Report.

We appreciate it Ron!

Man oh man, this is the stuff I live for! Rita Bennett is in so many films I’ve seen many times (all in the Something Weird Video catalog). Funny I always wondered if that sorta old fashioned “high class” accent was real or a put on…the ending like so many others is heartbreaking, but the loss of the film & scrapbooks is just sickening…how does one just dump a film, not even slightly curious? Ugh. This is also quite weird as I write for Dangerous Minds and some years ago I did a big story on Blonde on a Bum Trip (which led me to get those guys together for a full commentary for a rerelease blue ray from Distribpix-still waiting 😉) and a year or so after (or before) a large article about the Cheetah Club and there was some cool crossover here with both articles that didn’t have any crossover with each other. One last question…how do you know he was shot in the back of the head if his body was never found? Hmmmm? Again keep the greatness coming.

Howie – I think your question has already been answered in by AC in one of the previous comments to this piece.

“When Sammy Gravano flipped and testified against John Gotti he had to confess to every crime he had ever been involved with in order to get into the witness protection program. He was present when DiBi was murdered but another crew looked after disposing the body so he didn’t have those details. This is supposedly a common practice. Three can keep a secret if two are dead….”

Hope this helps…

The answer is: witnesses.

Will do Howie!

We did Teenage Housewife at 210 W 107 St #6D

with Bobby Astyr Susan McBain et al in 1970s…

He wanted to do it at our place on Fire Island but

that would not work with our German landlord.

McBain was living on a houseboat at 72nd St.

Astyr was a great guy!

It was funny seeing our apt in the film and then

they used our exerciser and it snapped!!! No one

hurt! I asked the other guy what he did to stay hard—

he said he meditated. McBain was hot!

Writing and investigating of the HIGHEST order!

I love what you guys do. Many congrats on an amazing body of work.

Thank you so much for the kind words Hans!

This may be a forgotten story to most, but not to us SI natives, who have had many discussions about this very incident.

(Also, judging by the original pic, I would say this is the 120 pct.)

Thanks for weighing in Tim!

Perhaps the passing reference to Pat Livingston, the Louisville-based federal agent who lost his mind somewhere between his agent life and his porn distributor undercover role, is a foreshadowing? That story is beyond RR-worthy, especially if you’re looking for your next film option deal.

Thanks so much George!

Holy shit! Incredible research and writing. How a simple photo can spin out into such a multi-layered story is awe inspiring. Too many performers end up living desperate, forgotten lives. If your only achievement was to illuminate and remember those lives, it would be enough. But you do so much more than that. Nothing but admiration for you folks.

We’re really grateful for that Phil!