Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

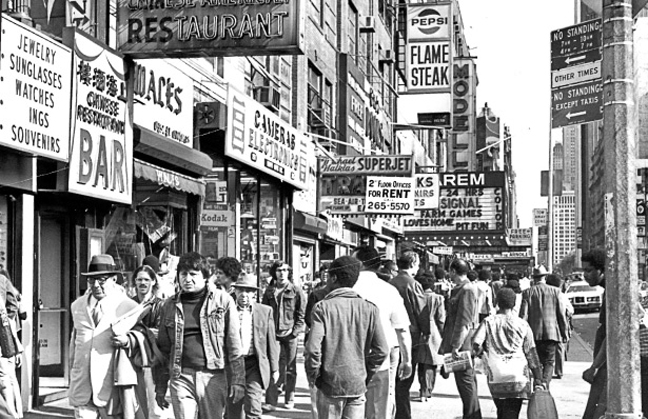

The 1970s was the decade of adult films and theaters in New York City. It started out with cheap and crude black-and-white softcore films, enjoyed the breakthrough of porno-chic spearheaded by the landmark film Deep Throat (1973), and ended with big-budget films that looked like regular Hollywood films – with fully explicit sex.

At the one end of the spectrum were champagne directors like Radley Metzger, Chuck Vincent and Joe Sarno – experienced filmmakers who turned their skills to the new and commercially attractive market for pornography by making sparkling, sophisticated or humorous movies.

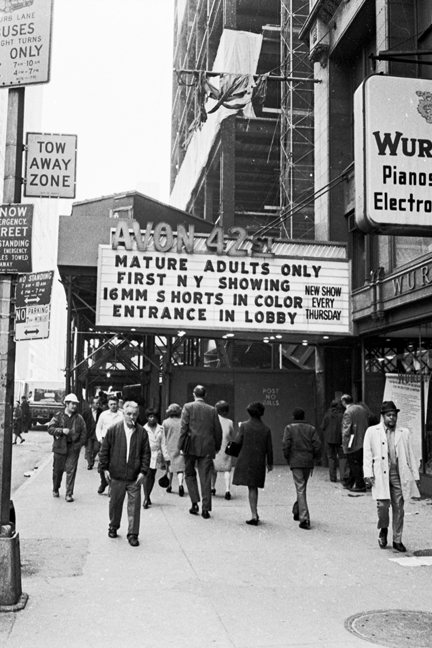

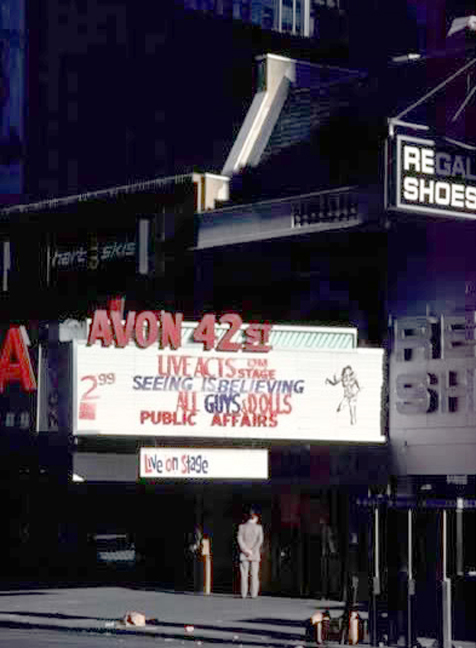

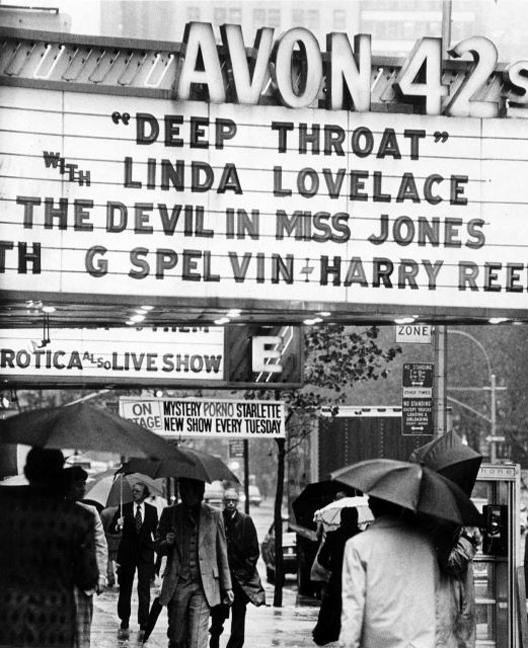

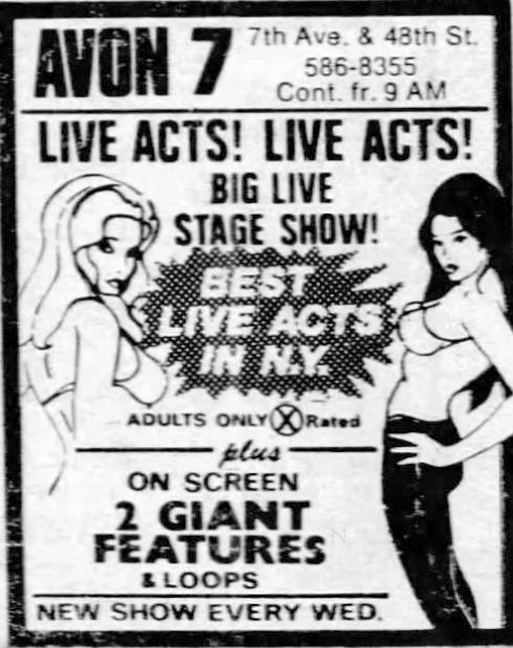

At the other end of the scale were the Avon films, a series associated with the chain of New York XXX theaters that included the Avon 42nd St, the Avon Love and the Avon 7. The Avon films form the sleaziest chapter of golden age adult films. These were not the mythical cross-over movies that would entice mainstream viewers into the theaters.

In fact when U.S. President Ronald Reagan ordered a comprehensive investigation into pornography in the mid 1980s, the resulting report held up examples of the most reprehensible films – and Avon films were top of the list.

So who was behind the theater chain? Where did they find people to appear in the movies? And who made these strange, violent films that still endure today?

Today The Rialto Report starts a multi-part look into the Avon empire, an untold history that stretches back almost a century.

This podcast is 62 minutes long, and is accompanied by the written article below.

With thanks to George Payne, Estelle Scheier, Elizabeth Trotta, N. Carroll Mallow, Mildred ‘Mickey’ Offen, Brian O’Hara, ‘Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville’ by David Freeland (NYU Press), byNWR.com and many others who contributed to this oral history.

The musical playlist for this episode can be found on Spotify.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Prologue: The Ghosts of George Payne

The phone rings with an insistent tone. It’s George Payne. The phone always rings more urgently when George calls. It matches his impatient manner.

His rasping movie-trailer-voiceover-ready tone is unmistakable and, as usual, he starts without preamble: “I’ve been thinking about the Avon films. We made them at Vince Benedetti’s Adventure Studios in Queens.”

George has perfected the art of stream-of-conscious questions, and they tend to emerge in reverse order.

“Why don’t we go over there and take a look? What happened to that place? What are you doing today?”

I point out that Vince died a few years ago, and that he’d sold Adventure Studios a few years before that. There’ll be nothing left there now, I say.

George continues obliviously: “So many films were shot there. All the Avon films. OK? All the crazy Phil Prince movies. And they were the wildest films I ever starred in. The wildest that anyone ever made.”

There’s a pause as if George has been swallowed by a wave of misty-eyed nostalgia, or perhaps it’s PTSD.

“The Story of Prunella. Tales of the Bizarre. The Taming of Rebecca. OK?” George lists film titles as if they’re cake ingredients. I’m concerned for anyone who may be overhearing his side of the conversation.

“Kneel Before Me. Forgive Me, I Have Sinned. Dr. Bizarro. Oriental Techniques in Pain and Pleasure. OK?”

Another pause.

“What time shall we meet there?” he asks.

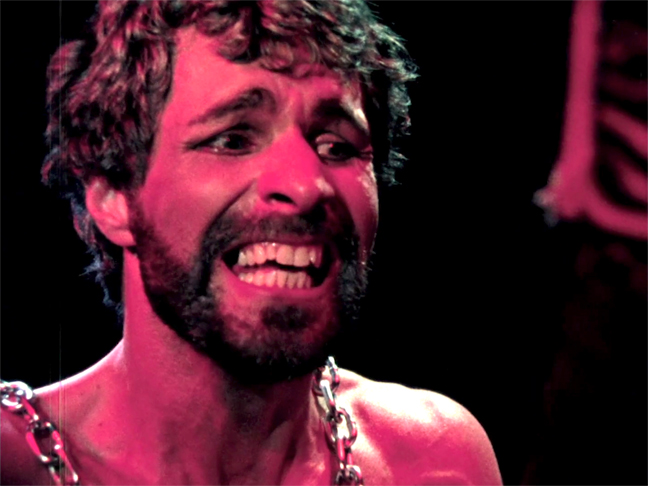

George Payne in his Avon heyday

George Payne in his Avon heyday

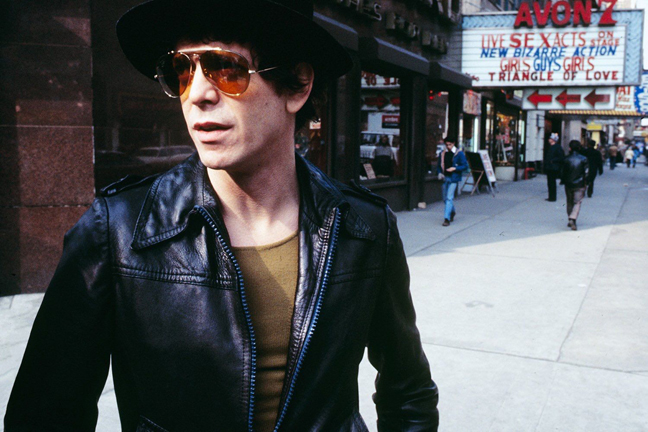

George is right. The Avon films were wild. Over thirty years after they were made, they remain the most singular and controversial series of New York adult movies. Even today, they occupy a cult-like niche in porn film history, which is all the more remarkable given how they were made: budgets rarely exceeded $15,000, shoots seldom took more than 72 hours and most cast and crew members had little experience in the grammar of film. And then there was the sex: raw, violent, confrontational and jarring. Often it was as far from titillating as you could imagine. It was a dislocated, cracked vision of the power of sexual dominance.

Avon films’ only success was at the box office: they weren’t just ignored at the industry award ceremonies that attempted to provide a façade of respectability to pornography, they were swept so quickly under the carpet that they were barely even noted. This wasn’t how XXX bigwigs wanted to present themselves to an already porn-skeptical public. The holy grail of mainstream crossover success would never materialize if Avon films were allowed to be the norm.

But these are also the reasons why Avon films have endured. In an era where any kink can be satisfied in some dark and forbidden corner of the internet, the Avon films still have the power to shock.

George Payne was Avon’s top dog in front of the camera. Not only the most ubiquitous presence, but also the most electric. No actor has committed more to his craft than George. No halfway measures, just a complete dedication to unhinged characters. In the Avon films he screamed at the actresses, casually dispatched violence and trembled on the knife-edge of insanity with an uncontrolled fever. He seemed to be having a meltdown before your eyes. And perhaps he was: for years, he was a speed freak without a home.

Today the same intensity still resides within him, though it’s aggravated by a recurring paranoia about his past. We meet up a few hours after his call. As he walks towards me, he eschews small talk. He’s jittery, but no more than usual: “I just got recognized on the bus on my way here. A middle-aged lady. She knew who I was. It was instant. I could see it in her eyes. I don’t know where she’s gone, but I’ve gotta’ be careful around here. OK?”

George brings his intensity back to the home of Adventure Studios

George brings his intensity back to the home of Adventure Studios

It’s a scorching hot day in Corona, Queens and the bodegas that make up the neighborhood spill their wares and customers onto the sidewalk. We find the old Adventure Studio straight away, even though it’s now masquerading as a furniture store. Its appearance is just as I expected – an anonymous space with no vestige of its former existence. We enter to find it filled with discounted wardrobes and vinyl recliners.

Just when I consider the trip to have been wasted, I turn to see George. He’s lost in a dream world, eyes glazed over, seeing events and objects that are no longer physically there. He touches the walls, caresses doorframes and provides a non-stop commentary: “I fucked Vanessa right here in this corner.” Or, “This is the room where the girls did their make-up. And their coke.” At one point, he tries to get behind an armoire to find the initials that he and Jerry Butler once carved into the wall. He then wanders out into the park that sits opposite the building and continues his stream-of-conscious description of the exterior scenes shot there.

George lost in memory at what once was Vince Benedetti’s Adventure Studios

George lost in memory at what once was Vince Benedetti’s Adventure Studios

After an hour in the heat we need refreshments, so I suggest lunch at a nearby diner.

Whenever we meet for a meal, George always places the same order: hamburger, well-done. Toasted bun, dry. A side of bacon. Leave out anything green. And lots of sugar in his coffee. I mean, lots. He doesn’t measure it out by the spoon. He pours it straight into his cup for what seems like minutes on end. The effect jolts him into an even more highly-strung state. It can be difficult to clutch at the scattergun threads of his thoughts.

“I shot my first porn loop in the late 1960s with Aaron Kaplan. In the 1980s, Aaron was involved in some of the Avon pictures. And he dated Paula Ciccone, Madonna’s sister who was flat-out crazy. And she was on drugs. We used a blow-up doll. Only because the actress didn’t turn up for the shoot. I burst the doll when I came on its face. I wish I had a copy of that.”

Slow down a little, George, I say. Tell me more about the Avon films.

George reminisces about Avon Productions

George reminisces about Avon Productions

George starts again: “You want to know about the money, the girls, or the films? Because different people were involved. OK?

“There was Murray the Jew. No one knew him, but he had the money and put everything together so it could all happen. Without him, there was no Avon.

“There was Billy. He was a biker who supplied the kinky girls that filled the Avon films. Girls like Velvet Summers. Ambrosia Fox. Cheri Champagne. They’d do anything for him.

“Then there was Phil Prince. The films were his twisted vision and each movie was more extreme than the last. Phil made us do things nobody believed possible.”

George sits back and looks around nervously: “The story of Avon is a jigsaw, OK? Guys like Murray the Jew. Billy the Biker. Phil, The Prince of Porn. And others too. Each has a different piece. There’s no single story, there’s just different threads.

“But begin with Murray the Jew. Because that’s where it all started.

He pauses.

“Now what does a guy have to do to get some more sugar around here?”

*

Murray’s story

In the summer of 1963, Elizabeth Trotta was bugging her boss at the Newsday offices. She was a gritty 26-year-old female reporter who was sick and tired of being given un-gritty female reporting assignments. She wanted something more challenging, perhaps even exciting.

Her boss waved her away. He told her she could get a job as a taxi dancer if she didn’t like it. So Trotta did just that.

Well, sort of. She went to work undercover as a taxi dancer in the murky nocturnal world of New York taxi palaces. She’d heard the rumors of illicit sexual shenanigans going on. Everyone had. Maybe she could use her femininity to find the truth and get a journalistic scoop.

Taxi dancers were young women who danced with men for money, often in rooms of city-center brownstones. The name was derived from the ‘more time, more money’ model of a cab ride. The phenomenon had reached its peak during the 1920s and early 30s, when as many as 250 dance halls filled the city and became an alternative for women to the narrow set of professional opportunities prescribed them. Female dancers customarily earned 50% of each 10-cent dance ticket, and so energetic young women could easily take home up to $40 a week – significantly more than teaching or nursing was offering.

Taxi dancers were young women who danced with men for money, often in rooms of city-center brownstones. The name was derived from the ‘more time, more money’ model of a cab ride. The phenomenon had reached its peak during the 1920s and early 30s, when as many as 250 dance halls filled the city and became an alternative for women to the narrow set of professional opportunities prescribed them. Female dancers customarily earned 50% of each 10-cent dance ticket, and so energetic young women could easily take home up to $40 a week – significantly more than teaching or nursing was offering.

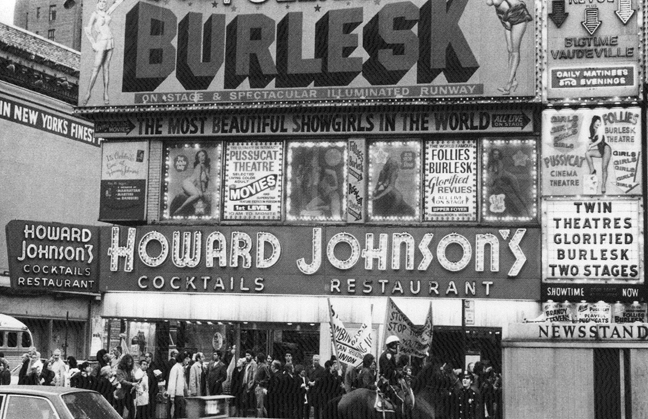

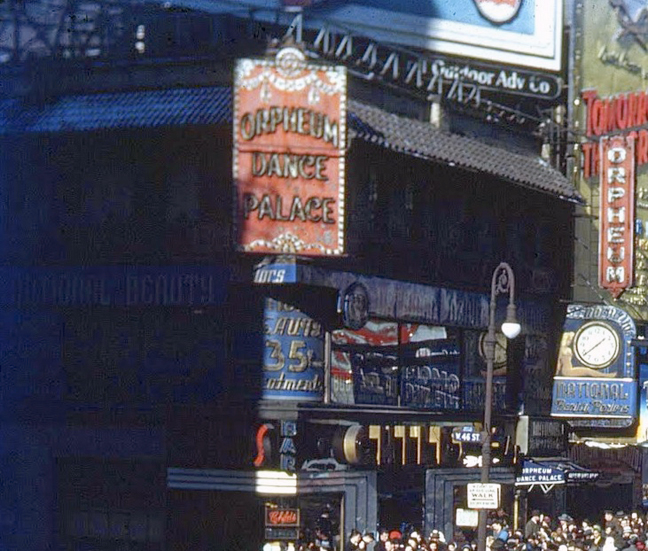

The most famous and venerable of taxi palaces was the Orpheum Dance Palace. The Orpheum sat at the corner of 46th and Broadway, in the same building that later hosted the anachronistic Howard Johnson’s restaurant and, much later, the Gaiety Theatre male strip club. It had opened in 1917 and was renowned for attracting the most beautiful dancers in the city. A sign on the wall in those days reminded patrons, ‘No Indecent Dancing.’ It was here at the Orpheum in 1923 that a 31-year-old aspiring writer named Henry Miller met and became obsessed with a beguiling young dancer named June Edith Smith (a.k.a. Mansfield). This meeting initiated what would become one of literature’s most famous love affairs, which Miller wrote passionately about in his semi-autobiographical Tropic of Capricorn.

The early days of Taxi Dance Halls

The early days of Taxi Dance Halls

In the book ‘Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville’, the Orpheum Dance Palace is described as follows:

Outside, at street level, the male patron was lured with enticing images of glamorous or busty pin-ups, accompanied by taglines such as ’50 Beautiful Lonely Hearts to Dance with You!’ After walking up a narrow flight of stairs, he would approach a small window – at the Orpheum it read ‘A Refined Place for Refined People’ – and purchase a roll of tickets, usually 10 for $1, or 10c per dance.

The women were ready to entertain at the Orpheum Dance Palace

The women were ready to entertain at the Orpheum Dance Palace

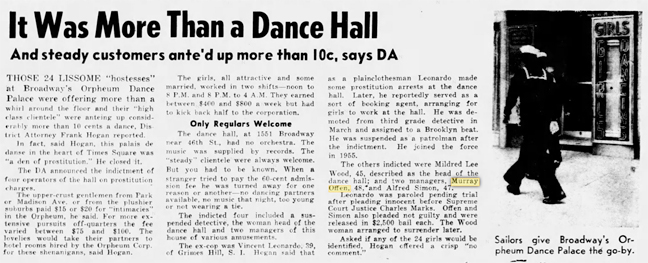

By the 1950s, times had changed, and cheap dances with anonymous floozies no longer cut it for the lonely and horny thrill-seeker. The Orpheum had to adapt and offer men a whole lot more than just a suggestive Salsa if it wanted to survive. So what had once been New York’s most famous ‘dime-a-dance’ hall reinvented itself along more sexual lines – and the architect of the change was a small-time Jewish gangster from the Bronx named Murray Offen.

*

Murray Offen was born in 1916 to a Jewish working-class family. His father, Nathan, had toiled all his life in office jobs, barely scraping together enough money to raise his six kids. Murray, Nathan’s second eldest child, and his older brother Sam had no desire to follow in their father’s heartworn footsteps. The boys had two more pressing interests: hustling, and hanging out at night in the underworld nightspots of Times Square. And preferably, doing both at the same time.

Sometimes Murray tripped up and ran afoul of the law, like when he was caught in 1942 mailing illicit drugs through the U.S. postal system. He was arrested for the scheme, but claimed he was merely sending a drugstore prescription to a sick friend and was unaware that the package contained opium tablets. The judge didn’t buy it. Murray entered a guilty plea, waived his right to counsel and was fined $250 and sentenced to five years’ probation.

Murray and Sam bounced around jobs – Murray worked in bars and nightclubs, while Sam managed adult bookstores – and both became familiar with everyone who was anyone on the Deuce, from low-lifes to cops and all those in between. On the streets of the old Times Square, everyone knew Murray and Sam.

Murray particularly enjoyed the company of the girls at the taxi dances and befriended one in particular, a young woman from Kentucky, name Mildred Lee Wood. Mildred – who went by her middle name Michelle, or more often ‘Mickey’, at the dance hall – told Murray how the girls made money at the dances. Really made money, that is – and it wasn’t from dancing. As with many of the taxi dancers, she raked in cash by ‘propping’ customers: taking their money with a promise to meet for sex, and then never showing. Sure, the duped dudes knew exactly where to find the hustling hussies the following day to demand their money back, but few were inclined to raise a ruckus. The sexual shame and risk of exposure overwhelmed their mere financial loss.

Murray listened to Mickey, and smelled opportunity.

Murray was sweet with the owners of the Orpheum and in the mid-1950s convinced them he could turn around the failing dance hall business. Privately, he wanted to expand the franchise into sex: dancing was dying, ‘propping’ was a short-term win, but prostitution would earn repeat business. That was a sustainable business model and he saw lucre in it. Sure, the Orpheum had weathered periodic crackdowns over the years as righteous committees and moral crusades were launched to clamp down on indecency and crime in places of entertainment. But Murray knew he could take it to the next level. He knew the streets and understood the fix.

Judging that a woman at the helm of the new business would cut a less suspicious profile, he persuaded Mickey to front the venture while he would make it all happen behind the scenes. It was a perfect fit: Mickey managed the dance girls; Murray took care of the rest. Together they were the Bonnie and Clyde of the sex-dance scene.

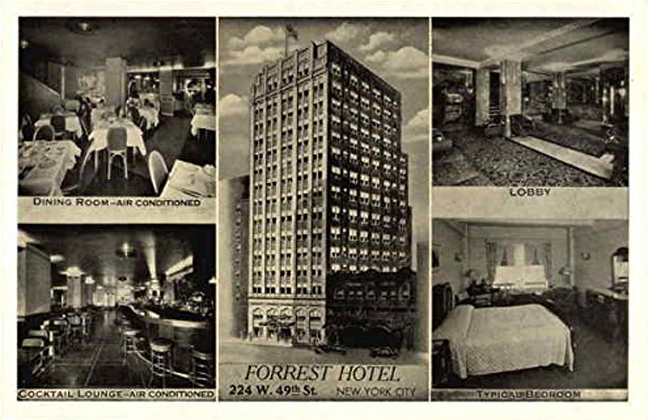

The new business model worked well: twenty-four girls worked their terpsichoric skills in two shifts – noon to 8pm, and 8pm to 4am – and sold on-site ‘intimacies’ for $15 to $25. If clients wanted more, they were directed to the nearby Forrest Hotel at 224 West 49th St – rooms 1111 and 1604 in particular – where the going rate for a dancer’s extra-curricular services was $100. And if patrons wanted anything else, Murray was happy to oblige: a stag party where three dancers serviced 15 men. An orgy for a group of visiting businessmen. The occasional S&M torture session. Murray took up permanent residence at The Forrest Hotel so that he could keep a close eye on the activity. (The same hotel was notable for housing other New York characters: Damon Runyon lived there in the 1930s, as did Jack Benny, and George Burns and Gracie Allen later. It is still operating today as The Time Hotel.)

New York’s Forrest Hotel, where men paid women for more than just a taxi dance

New York’s Forrest Hotel, where men paid women for more than just a taxi dance

From the get-go, Murray lived and breathed the new business. There was no limit to his job description: he applied to the city for the business licenses and permits. He decided who was let into the palace each night, turning away suspicious-looking men by claiming they were dressed inappropriately or by saying that he didn’t have enough dance partners working that night. He threw out unruly guests in a brawny manner, threatening them with bodily harm – or worse, public exposure – if they returned. And he patrolled the dark corners of the Orpheum to ensure that nothing more than hand or blow jobs were being provided.Most importantly, Murray brokered a deal with the cops. Starting in 1944, control over the city’s dance halls had been turned over to the Police Department from the License Bureau. Murray had lots of friends on the force and uniformed officers were a regular fixture at the venue, enjoying the company of the young dancers. Murray’s business operated under the radar thanks to strategic contributions to the euphemistic ‘Policeman’s Ball.’

As an added measure of protection, Murray also brought onboard a young undercover detective named Vincent Leonardo. Vincent had been sent to the Orpheum to investigate vice, but left as an Orpheum employee paid by Murray. He kept New York’s Finest at bay, and developed a feeder system, grooming new girls he found at the police precinct when they were dragged downtown for unrelated vice activity. Vincent provided a sleazy synergy: a vertically integrated business that was practiced horizontally.

To the outside world, Mickey was the queen bee, lording over the harem of harlots, knowing when to be tough and when to be tender. She was bossy, assertive and opinionated. She’d meet prospective girls at the Howard Johnson’s in the same building as the Orpheum, and decided which were reliable and could make money. She and Murray would procure fake IDs for underage girls and provide birth control (or arrange back-street abortions if the contraception failed). It was Mickey who made sure that the Orpheum’s reputation for having the prettiest and wittiest girls in the business thrived.

The Howard Johnson’s where Stella met her prospects

The Howard Johnson’s where Stella met her prospects

The scuttlebutt was that Mickey was a lesbian, living in a fancy Upper West Side apartment at 11 Riverside Drive with her girlfriend Rebecca, one of the Orpheum high-earners and twenty years Mickey’s junior. Another piece of tattle was that Mickey was sleeping with a police lieutenant to keep the boys in blue in check. Stories like these were dismissed by some as disparaging rumors spread by a malcontent dancer.

Whatever the truth, business was good. The Orpheum’s financials were simple: clients were charged an entry fee which covered the business overhead, but the real money came from the working girls. The girls had to pay the management team half of every dollar they made – whether from dancing the Rumba or performing the horizontal Mambo. This payment was split four ways between Mickey, Murray, Vincent Leonardo and another theater manager, Al Simon. The girls earned at least $800 a week, meaning that each of the four-strong management pocketed $100 per worker. With 24 girls beavering away, this added up to over $120,000 per year for each of the managers – or around $1,200,000 in today’s money. And this didn’t include some of Murray’s additional sideline activities.

The money flowed in for several years, and life was good. A tall, graying man whose pale, rice-paper complexion suggested an unfamiliarity with the midday sun, Murray always seemed older than he was. Murray was a taciturn man, given to communicating through complaints, but he was leading a charmed and lucrative existence. But with the new-found income, he now assumed the role of family provider. Murray even helped his brother Sam buy into a 42nd St. store that sold cheap tchotchke.

In 1952 Sam had had a son named Elliot, and Murray doted on the boy. Murray spent each morning before the Orpheum opened with Elliott, teaching him the ways of the world. Elliot’s mother, a chronic OCD-germaphobe, had instilled a fear of germs in him, so Murray taught the kid how to stay fit and healthy. In many ways Murray acted as a surrogate father to Elliot.

But the Orpheum business was built on secrets. And perhaps the biggest of all was that in the late 1950s, Murray had quietly married Mickey. What’s more, they’d had a baby girl, Melissa. She was known to everyone as Honey Bee.

*

In 1963, Murray and Mickey’s world was turned upside down and their gravy train derailed when upstart reporter Elizabeth Trotta went undercover to expose the dark side of the taxi dance palaces.

Reporter Elizabeth Trotta goes undercover to expose the darker side of taxi dancing

Reporter Elizabeth Trotta goes undercover to expose the darker side of taxi dancing

Ironically Trotta didn’t choose the Orpheum, instead infiltrating the Parisian Danceland – a smaller venue just one block away – but the result was the same. Her expose’ blew the lid off the taxi dance business. Her story, published in Newsday across three consecutive days in July 1963, revealed the sordid underbelly of the dance palaces for the first time. The series was a sensation, and Murray and Mickey were on the front line.

Trotta described working for “fifty-six hours of trampled toes, sweaty palms, whisky breath, smutty jokes, forced smiles, cheap hair tonic, and a fearful dread of making a slip – such as good grammar.” More critically, she explained ‘propping’, and indicated that she could have earned much more if she’d taken advantage of other opportunities open to her. Gay Talese, future pioneer of New Journalism, weighed in with an article in the New York Times. In that article, Mickey’s supposed-squeeze Rebecca offered a case for the defense: “I am helping people. New York is a cold, cold city, and men can talk to us.”

The New York authorities sat up and took notice. They had to: a network of whorehouses operating nightly in the heart of the City of Dreams was not just an embarrassment, it was unforgivable. Undercover officers were sent into the dance halls, and emerged confirming the news stories. Press statements were released revealing they found the hostesses “indecently exposed, immoral while dancing, and willing to proposition the male visitors.” Frank Hogan, New York District Attorney, described the girls as “lewd” and called the Orpheum a “den of prostitution.” On the bright side, he conceded that it catered to a “high-class clientele”.

The media and law enforcement expose the true nature of Murray’s business

The media and law enforcement expose the true nature of Murray’s business

In January 1964, the Orpheum’s license – in place for almost 50 years – was revoked. Murray and Mickey kept the place limping along while they appealed to the State Supreme Court, but the writing was all over the wall. By March 1964, the City Commissioner effectively signed the death certificate for the Orpheum, and four other taxi-dance halls, by refusing to renew their licenses.

Shortly afterwards, the cops swooped in and arrested the entire Orpheum gang: Murray, Mickey, Leonardo and Al were all taken in. On April 24, 1964, all four defendants pled not guilty to multiple counts of prostitution and conspiracy. Unsurprisingly Vinnie Leonardo was suspended from the police force. As the group’s nominal front, Mickey took most of the heat from the newspapers fascinated with the madame with moxie. Murray was released on $2,500 bail and carefully slipped into the background, painting himself as a mere dance hall manager.

The jig was up when the licenses were denied

The jig was up when the licenses were denied

*

If this seemed like the end of the road for Murray, the opposite was true. The New York District Attorney stated that, “It is hoped that the individuals will have learned their lesson.” That was actually true: Murray had learned his lesson. He vowed that next time he would do it properly. He would do it by himself, operate on a bigger scale, avoid overt prostitution with its higher risks, and cover his own tracks to the point of enveloping himself in elusive anonymity.

Murray’s new vision was to buy into the market for small cash-cow grindhouse theaters that were cheap to run. He saw the growing success of Chelly Wilson, who exhibited exploitation films in a theater portfolio that would grow to encompass the Eros, Cameo, and Tivoli (later the Adonis). He wanted in on the action.

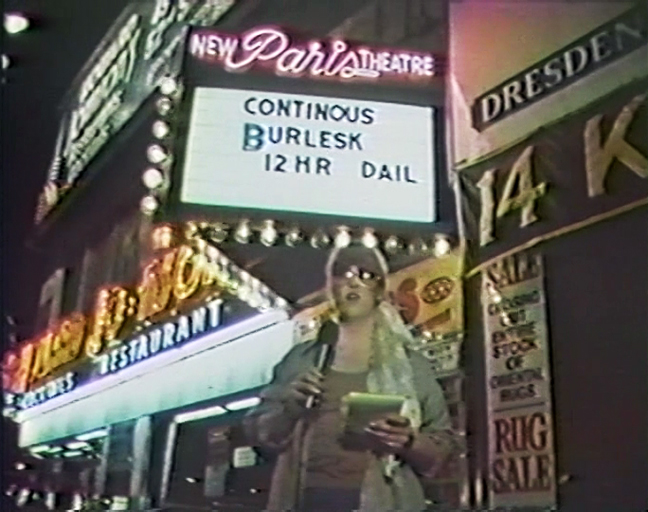

At first, Murray lay low. He bided his time, helping raise his daughter Honey Bee and nephew Elliot. Then in the late 1960s, he emerged as the new leaseholder for the old Orpheum space, which he turned into a theater he called the Paris. Murray soon added more locations, taking out long-term commercial leases, some of them lasting 20 years or more, on various shoebox theaters in the Times Square area. He gave many of them the ‘Avon’ name: there was the Avon Hudson, Avon Love, Avon 7, Avon 42nd St. He chose the ‘Avon’ moniker because he wanted a wholesome brand, one that belied the sordid activity inside, and the name of the door-to-door cosmetic salesforce company seemed as good as any.

Murray begins building his Avon empire

Murray begins building his Avon empire

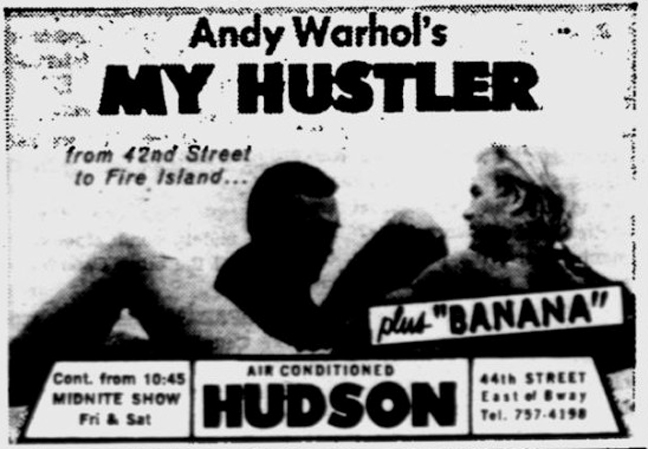

But one of the first theaters in the portfolio was the grand Hudson Theater, a once-great theatrical venue that had enjoyed a multi-faceted life, serving as a CBS Radio studio in the 1930s, and then home to The Tonight Show under host Steve Allen and later Jack Paar, until 1959. By 1967, under Murray’s direction, it was a cinema experimenting with artsie-exploitation fare like Andy Warhol’s My Hustler (1965) before succumbing to showing roughies like the Findlay’s The Touch of her Flesh (1967). The theater was rebranded as the ‘Avon at the Hudson.’

Murray tried his hand at arthouse fare before moving on to sexploitation

Murray tried his hand at arthouse fare before moving on to sexploitation

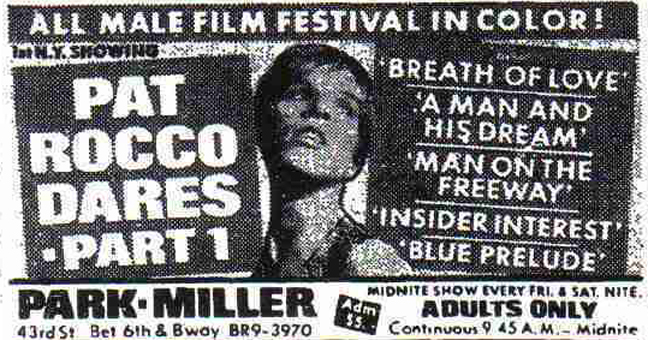

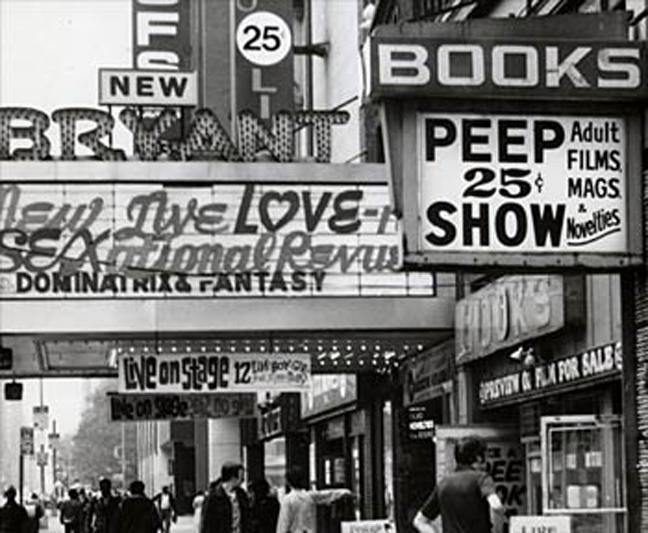

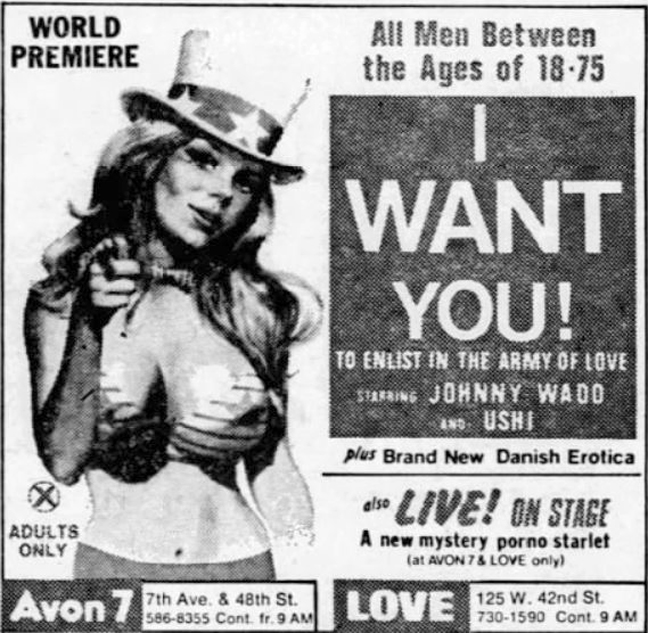

Next up was the Avon Love which exhibited the country’s first split beaver loops, many imported directly from Howard Ziehm in San Francisco. Avon Love’s gay counterpart was the Park-Miller with its focus on shorts, including the first New York exhibition of Pat Rocco’s beefcake films. The Avon 7, a 260-seat basement theater, opened in late 1970, followed by the Doll which also had a live sex show on stage in between features. Murray turned the Bryant into a hardcore venue called the ‘New Bryant’ (it had previously screened exploitation fare like Andy Milligan’s ‘Tricks of the Trade’ or Robert Downey Sr.’s ‘Sweet Smell of Sex’), and unleashed the 220-seat Avon 42 which sat at 133 West 42nd St.

Murray is the first to screen Pat Rocco’s films in New York

Murray is the first to screen Pat Rocco’s films in New York

Occupying the former Orpheum location, The Paris – sometimes known as the ‘New Paris’ – was a strange beast. It was less a conventional theater, more of an early live sex show space, a progenitor of Show World and its ilk. Adult film actors Jamie Gillis, Alex Mann, and Jason Russell with his wife Tina, all recalled working there at the start of their careers. Their description of the set-up was consistent: a single mattress (stained, springs exposed), fold-up chairs (metal, noisy as people shuffled to get a clearer view), and a buzzer system to warn the performers of any unwelcome visits from law enforcement. Jamie Gillis provided socially redeeming interludes, reciting Shakespeare and Joyce, just in case any undercover vice cops were present. In between the sex shows, 8mm loops were projected on a makeshift screen. Live sex shows soon spread to other Avon locations.

At times, Murray encountered credibility difficulties because of his long rap sheet dating back to the 1940s, but he fought back against these obstacles. In 1971 for example, he petitioned the district court to set aside his 1942 conviction for postal drug distribution, claiming he hadn’t understood the guilty plea he originally entered. That plea was denied, but Murray was undeterred, and continued accumulating properties and turning them into sex film theaters.

It was a turbulent time for adult theaters. If the operators weren’t being busted for obscenity or shut down by their landlords, they were under attack by you-name it: sometimes from the competition, sometimes from the mob, and sometimes from the competition that was the mob. Firebomb attacks were not uncommon, and alliances sometimes needed to be formed. In 1971, Murray joined forces with Nathan Mallow (aka N. Carroll Mallow), a fellow theater operator whose own portfolio included the San Francisco Theater on Broadway between 45th and 46th Streets and the Paree Adult Cinema and Live Show at 753‐9 Seventh Avenue near 49th St. Together they opened the Hollywood Twin Theater at 777 8th Avenue, which later became the 777 Theatre. Speaking years later, Mallow spoke to me about various massage parlors they opened as well – including one on Broadway and 47th St. where you could have all the sex you could handle in 24 hours for $30.

The (New) Bryant was among Murray’s stable of adult theaters

The (New) Bryant was among Murray’s stable of adult theaters

Mallow was less prudent than Murray, and had a habit of being arrested for obscenity, prostitution, and securities fraud, so Murray soon distanced himself from his partner. Murray’s years operating on the fringes of the law had taught him valuable lessons, and he wasn’t interested in exposing himself to needless risks. His growing empire wasn’t immune to legal issues, but he usually emerged largely unscathed – thanks in part to the regular payments to cops, the so-called contributions to ‘The Policeman’s Ball’, that had started when he managed the Orpheum.

Murray also recognized the importance of security at his theaters – so he invested in it. He hired people who would snuff out trouble before it got out of hand. It was a simple logic: fewer on-site disturbances, whether due to assaults or drugs, meant less bad publicity, not to mention a slightly more welcoming environment for the customer.

But Murray’s overriding golden rule was discretion. He made sure he stayed in the background, delegating management of the business to a trusted few. In fact very few even knew his real surname – on the street, he was simply ‘Murray the Jew.’ Up to this day, no one has identified his connection to Avon.

That would have pleased Murray the Jew.

*

Murray’s operating model was low maintenance by design and choice, but it soon grew to a size where he needed additional full-time management.

Estelle Scheier was Murray’s most trusted ally. Estelle had been Mickey’s best friend from back in the days when they were both fledgling taxi dancers at the Orpheum, and was a hardnosed Brooklynite who could be relied on. Murray brought her into the Avon organization, first as office manager, then as a more senior officer of his holding company, Avon Theaters. Murray’s intention was simple: just like at the Orpheum, he delegated the front-of-house day-to-day running of the business to a woman so he could disappear into the shadows and watch from the sidelines as he brokered the real deals.

Estelle was fine with that, but to cover her tracks she created a new identity, calling herself Stella Stevens after the Hollywood showgirl.

In 2009, I visited Stella at her retirement home in South Florida. She was still up to her eyeballs in administrative paperwork, but now it related to her voluntary role as treasurer of her living community’s condominium association.

Stella can be seen in Brian O’ Hara’s short documentary, ‘The Prince of Porn’. It shows her to be a smiling, good-natured yenta, a benign mother-hen among porn urchins. Mrs. Garrett from the ‘The Facts of Life’ would be an era-appropriate resemblance. Twenty-five years later, she was much the same. She was welcoming and warm, though circumspect and curious as to why I was interested in her office job from years ago. She answered my questions with an eyebrow perpetually raised.

She’d been brought up in Brooklyn in the 1930s. She was good at school and enjoyed languages – her high school year book indicated a future as a Spanish stenographer – but opportunities for women were limited. She’d married once, briefly and unhappily, when she was barely out of school. Then she became a taxi dancer in the early 1950s, and found herself earning more than any of her girlfriends, and more than most men of her generation too.

I ask about her background before she started working for Murray. She laughs at the suggestion that she’d been a ‘1950s cheesecake model’ as reported by Bill Landis in his article, ‘The Avon Dynasty’. She and Mickey had paid to have pin-up photographs taken of themselves once, hoping for modeling or burlesque work, but they didn’t pursue it.

Stella warms to the memories she’s resurrecting, and describes how she managed the Avon theaters, each with its own distinct character and regulars. Each location sounds like an old friend. She still has her business card from the time, which shows her office address as the space above the Bryant Theater: “Stella Stevens, Avon Theaters, 138 W 42nd St, New York, NY 10036. Tel: 921-0080-1.”

I ask her what her formal role was. “For years I took care of whatever needed to be done. And then I became the president of the company for Murray,” she announces with a smile.

It’s true: she pulls out the Articles of Incorporation of the Avon Theater company which list her as the most senior officer. She smiles slyly: “I got a kick out of the fact that people thought I was just Murray’s secretary or office manager.”

On a day-to-day basis, Stella took care of everything. She hired the projectionists, ticket-takers and handymen. She paid everyone, settled the bills and prepared the accounts. She diverted inquisitive eyes, quashed any potential disruptions and made sure the cops had no reason to grouch. She hired a small and loyal team who oversaw the actual running of the theaters, guys like the Irish duo, Phil Prince and Pat Rogers. She was the boss, and they all reported into her.

One of Murray Offen’s successful Avon theaters

One of Murray Offen’s successful Avon theaters

She remembers the details as if it all took place yesterday: the largely good relationships with the cops – thanks to the regular-as-clockwork brown envelope payments that Murray arranged. The lurid ads she placed in the newspapers. The rival theaters. The small team of maintenance men who kept the Avon grindhouses grinding no matter what. The strange rag-tag mix of people who were regulars at their theaters. The bizarre complaints she fielded – if only she had a dollar for every time a filmgoer demanded reimbursement for having his pocket picked by a long-fingered hooker. And the mob, often in the brooding shape of Matty ‘The Horse’ Ianniello of the Genovese crime family, who would emerge from time to time looking for their slice. Every day was different.

How involved was Murray? Stella spoke to him every day. He wanted a low profile, but he was all over the business like a rash. He knew which movies were playing well, and which ones were duds. He interrogated the projectionists to find what content people found most exciting. Or outrageous. Or both. He knew which films to pair as a double bill to entice the most jaded viewers. He was the conductor of a symphony who was standing in the dark.

What was their relationship to Chelly Wilson, doyenne of Times Square theaters? Stella answers with disdain: Chelly was competition, that’s all.

But was Chelly involved in the ownership of Avon in any way, as has been claimed in articles over the years? Stella is quick on the offensive: of course not. Who writes this shit? Besides, Chelly was a lying, devious pain in the ass. It was simple: Murray set up and owned the company, Avon Theaters. Stella became its president. End of story.

But what about other names who were listed as directors of Avon-related companies? Surely Murray must have had executive help from others? Sure, Stella admits, other people were brought onboard. Friends, associates, attorneys. Anyone who could facilitate a deal. Anyone whose name looked good on a legal document or in an application to the city for a license. These people were compensated for their time, their expertise, or their name, and then asked to get the hell out of the way so that Murray could run the business properly. They were peripheral: only Murray and Stella knew where all the bodies were buried.

I moved to change the subject, but Stella is stuck on Chelly Wilson: “Why does she get mentioned as the ‘Queen of Times Square’ in newspaper articles as if she owned everything? Murray owned more theaters, produced more films, and made more money than she ever did.”

I suggest that Stella already knows the answer to this: Murray designed his business to stay hidden.

Stella nods quietly.

Besides, I say, lazy journalists have fallen for the idea of a female Greek émigré who started out with nothing and ended up pulling the strings in a male-dominated world of sex. No one has thought of digging beyond that.

I ask about Murray’s daughter, Honey Bee. Did she become involved in any way?

Stella’s mood visibly darkens.

*

In the mid-1970s, Avon moved into filmmaking.

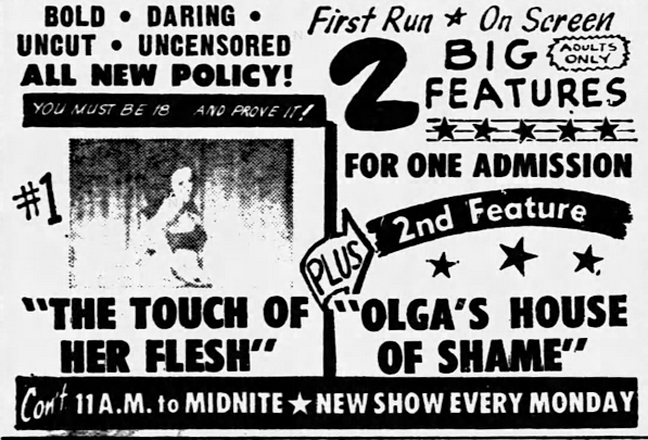

Since the 1960s, Murray had seen the success of ‘roughies’, movies which mixed sadomasochism with sex – S&M-influenced films like the stark black-and-white ‘Olga’ trilogy or the imaginative misogynistic violence of Michael Findlay’s ‘Flesh’ series.

The ‘Olga’ and ‘Flesh’ series that inspired Murray

The ‘Olga’ and ‘Flesh’ series that inspired Murray

Murray figured that he could hire a few wannabe-Scorseses to make cheap 16mm films guerilla-style – but with hard-core sex. They didn’t have to know the first thing about filmmaking – as long as they were shooting sex and following his instructions. Murray knew he could recoup the costs in a matter of weeks in his own theaters, and the rest would be gravy in perpetuity.

Because Murray understood what attracted the crowds. For a start, the title was important. It should emphasize the gender divide while validating the feelings of the downtrodden everyman who was considering shelling out the hard-earned bucks sitting in his damp pocket. If the one-sheets were brash and the tag-lines sufficiently obnoxious, men would buy the tickets.

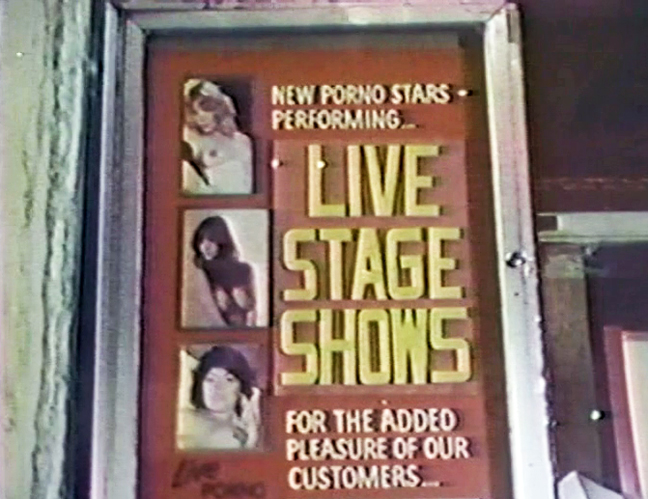

The first effort was Dominatrix Without Mercy. The poster shows an Amazonian dragging two slaves by the hair, with the tagline, “She Made Them Crawl! She Made Them Beg! She Made Them Suffer! And They Loved Every Painful Moment!” The film’s crude content matched its promise: bondage with ropes and chains, nipple-clamps, whipping, verbal abuse, a forced dog impersonation (!), and a golden shower. All this in a single film that is only just over an hour long. This wasn’t your grandfather’s stag movie. If it looked cheap, dirty and amateurish, that’s only because it was. But it packed a vicious gut punch.

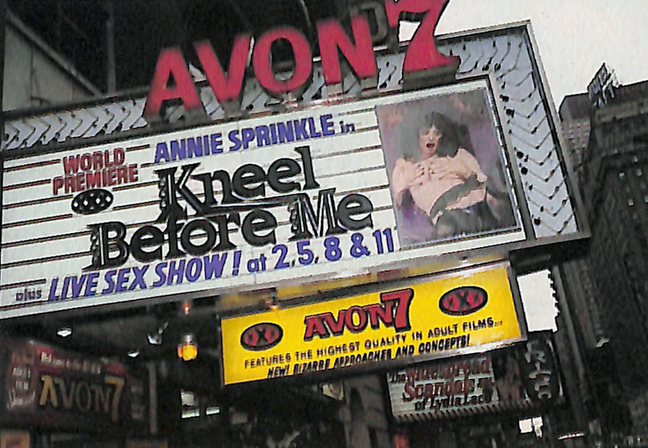

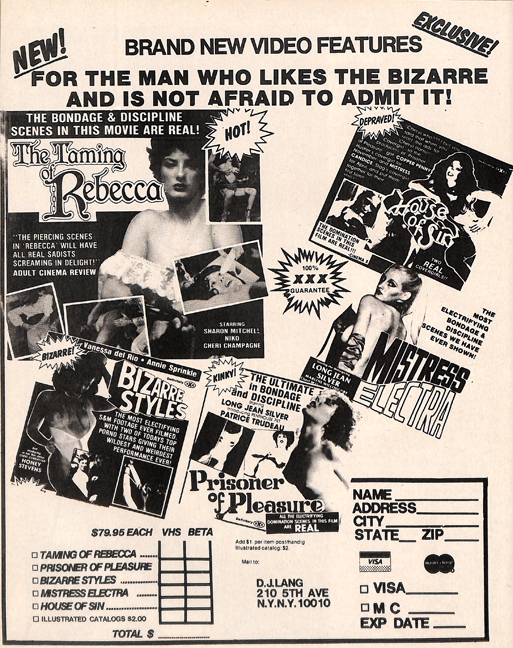

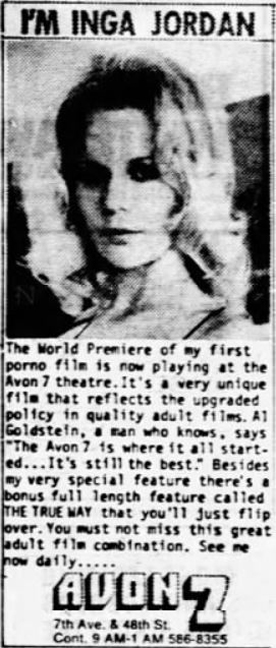

Subsequent Avon films continued the tradition of kidnapping, non-consensual sex, prostitution and extended S&M scenarios. They featured some of New York’s high-profile adult actors including Sharon Mitchell, Vanessa del Rio, Al Levitsky, George Payne and Annie Sprinkle as well as a mixed bag of undernourished and pale unknowns. And sure enough, whoever Murray hired to helm the pictures – whether it was Joe Davian, Mister Mustard or Carter Stevens – the films all had successful, extended runs in Avon theaters.

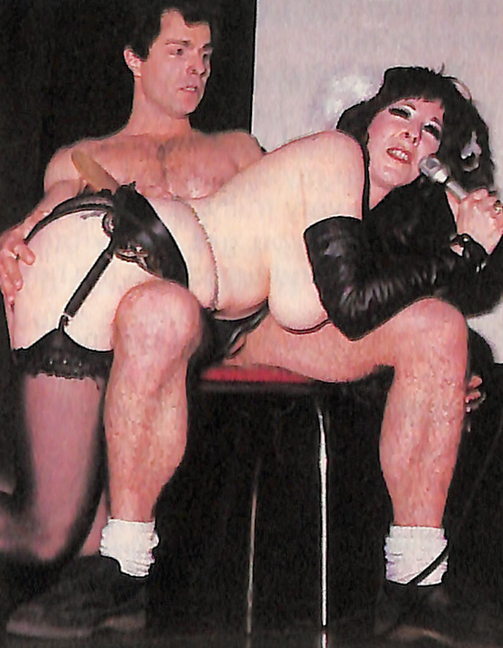

Annie Sprinkle performing live and the Avon 7

Annie Sprinkle performing live and the Avon 7

George Payne joins Annie Sprinkle for a live show at the Avon 7

George Payne joins Annie Sprinkle for a live show at the Avon 7

Avon’s most successful director was Phil Prince, an Irish American whose past included a stint as a live sex show performer, extensive racketeering, a murdered wife, and a life of crime spent on the edge of New York’s violent Westies gang. He’d been working for Stella in a number of capacities for years, and so Murray cut him some slack and offered him the chance to be a moviemaker. The ensuing films, perhaps not unsurprisingly, reflected a distorted and fractured world view. Phil had survived the seamier side of 1970s New York, and unapologetic violence and twisted sex were his response. He had no background in filmmaking, but his troubled psyche worked in his favor. The more he filled his films with sexual violence, the more people seemed to like them. A classic case of assault and flattery.

Murray Offen gave Phil Prince a shot at directing films

Murray Offen gave Phil Prince a shot at directing films

I point out to Stella that she was the star of one of Phil’s films: she was the sadistic Miss Zorda in The Taming of Rebecca (1982). She was convincing too, I tell her.

Stella laughs. It’d been fun being a bitch in front of the camera, letting herself go like that. The films were like a company day out, she says. Her mind rewinds a few decades and she tells funny stories of Phil Prince and the film’s main players, George Payne, Sharon Mitchell and David Christopher.

Sharon Mitchell, Stella Stevens in ‘The Taming of Rebecca’

Sharon Mitchell, Stella Stevens in ‘The Taming of Rebecca’

Making the films may have been a hoot, but I point out that they are shocking to watch, and were prosecuted as some of the most extreme examples of pornography ever made. As I say this, I’m suddenly aware how strange it is to be having this conversation with a sweet, silver-haired retiree. But Stella snaps back straight away: what appeared on the screen may have been jarring – shocking even – to look at, but the shoots were nothing more than entertaining freak shows. She did the casting for most of Phil’s films and enjoyed assembling a family of misfits. And it really was a family – no one could feel left out in a crowd like that.

Fans flocked to the violence of Avon films

Fans flocked to the violence of Avon films

George Payne was always an Avon fan favorite

George Payne was always an Avon fan favorite

Stella disappears for a few minutes before re-emerging with a large leather-bound ledger. It contains production records for the Avon films. God knows why she’s held on to it, but I’m glad she has. Dates, budgets, expenses, names, addresses, locations. All written in elegant penmanship. Random details abound: Phil Prince was paid $2,000 (plus a percentage) for Forgive Me, I Have Sinned, while George Payne received $200. Kneel Before Me was shot over three days, from November 18th to 20th in 1982. Exteriors of the reform school featured in ‘The Taming of Rebecca’ were filmed at the Oak Ridge building in Forest Park, Queens. The cast and crew ate from the 2nd Avenue Deli when making The Story of Prunella, and it was Ron Jeremy who claimed back the cost. Stella finds it amusing that I pore over the details as if I’ve discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls.

*

New York City was in financial crisis in the 1970s. The city’s economy was rocked by the decline of manufacturing and the flight of the white middle class to the suburbs, resulting in falling tax receipts that risked the city defaulting on its massive loans. It scrambled to patch together one plan after another, each intended to save the city from declaring bankruptcy while cutting back on the social and municipal services it provided.

But while the city was underwater, Murray was doing better than ever. The former Orpheum space had been turned over in 1975 to new management who started the Gaiety Theatre, a gay male burlesque house on the second floor of the building. But Murray was doing well from his network of porn theaters, XXX film production and prostitutes.

Live sex shows were a big draw for Murray too. The front of the Bryant was plastered with pictures of nude women with cut-out stars super-imposed over nipples and genitals. The marquee barked, “Our Famous Live Sex Acts on Stage” together with the latest movie title. Porn actor Michael Lawrence remembers performing live sex shows as a ‘love-team’ with his wife Brandy at the Avon 7 and Avon Doll locations. He also recalls future porn queen Veronica Hart starting there at the same time with a boyfriend.

Avon Theaters thrived on live sex shows

Avon Theaters thrived on live sex shows

Murray was rumored to be clearing a profit of some $50,000 per week, though this seems high. It would mean an annual profit of over two and a half million bucks, and if Murray made that kind of money each year in the 1970s, where did it all go? He wasn’t living extravagantly. He continued to keep a suite at the Forrest Hotel at 224 W 49th St., while Mickey raised Honey Bee away from the madness in the quiet apartment she still kept on the Upper West Side.

Some of the money went to his family. Thanks to Murray’s financial muscle, his brother Sam now owned a store on 42nd St. It was ostensibly a souvenir knick-knack shop, but it had evolved into a more useful stop-off. You could get a fake ID – and stock up on knives, nunchucks, poppers, ludes and porn while you were there.

Murray’s nephew, Elliot, would hang out at the shop, helping out from time to time. He was now in his 20s, and was a troubled kid. Since dropping out of high school several years early, Elliot had worked as a male exotic dancer, and then as a female impersonator. He had an eating disorder, and despite Murray’s mentoring got into scrapes of every color. Murray recognized his wayward self in the troubled kid and want to help him along, but as much as he’d tried to take Elliott under his wing, Murray had to admit defeat and recognize a lost cause when he saw one: his nephew’s unhinged behavior had started to resemble the plot of an Avon film.

Elliot had got married, but in 1979, it was reported that he’d kidnapped his 2-year-old daughter, Karen. Elliot claimed that he was fleeing a troubled relationship with his wife, and that he’d broken her fingers in a fight. Elliot took his daughter, along with new girlfriend Randi Jacobs, and together they went on the run for the next seven years.

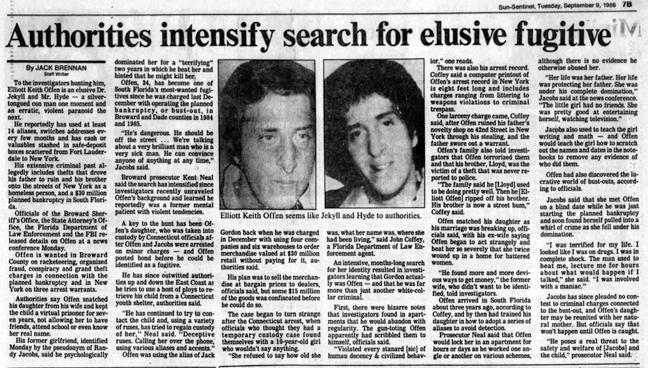

In 1986, Elliot resurfaced with a new scheme: he became the master of the ‘bust-out’ – the term for a financial fraud where someone buys goods on credit, doesn’t pay for them, then sells them for a profit on the black market.

With only a telephone, Elliot successfully fooled companies across the country into handing over products such as luggage, hosiery, active-wear, sportswear, handbags, footwear, lingerie, electrical tape, light bulbs and sunglasses. He would even arrange face-to-face business meetings to set up his victims for his theft. And he did it all by adopting a curious Texan-Yiddish accent that earned him the nickname ‘Tex-Moishe’ in law enforcement circles.

Elliot became one of the most wanted criminals in the country. Lt. John Kelly of the New York City Police Department described Elliot as “the most disciplined individual he’d ever seen in 25 years” – a true Jekyll-and-Hyde of crime. In response to Elliot’s fraudulent activity, Kelly assigned 25 detectives, 15 police vehicles and a helicopter to track the fugitive’s whereabouts.

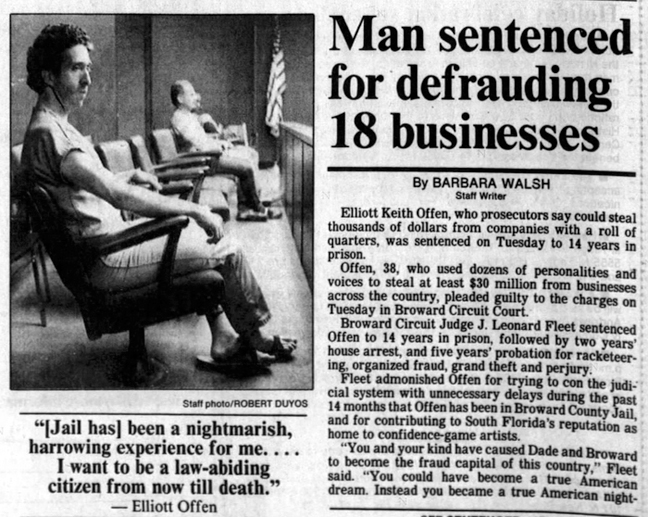

In 1988, Elliot was caught by police and taken to court. As much as Murray hated publicity, he came to Elliot’s help and arranged an attorney. The media loved the story. They described Elliot as a mastermind of criminal theft, able to “convince anyone of anything at any time”, and revealed that Elliot had reaped 30 million dollars from his crimes. Murray was described as a “pornography tycoon and adult film producer.” The high-paid attorney worked: despite being charged for 13 felony convictions, Elliott was only sent to prison for two years.

But Elliot’s troubles were far from over. After his release, Elliot was at the New York Stage Delicatessen with his father, Sam one day. Elliot thought that Maître D’ Joseph Corsin was disrespecting Sam, so he violently attacked Corsin, punching him four times in the jaw. 300 people at the Delicatessen witnessed the event unfold, and Elliot himself claimed he left Corsin for dead. The police were called, and once again Uncle Murray intervened to smooth the waters. Elliot and his father were required to pay Corsin $7,500 to repair the damage to his teeth, but avoided further sentencing.

*

In the 1980s, Stella was still managing the Avon business, though the increasing crime in Times Square was giving her more headaches each day. She asked Murray for help in the office, and an assistant came in the form of Murray’s daughter, Honey Bee.

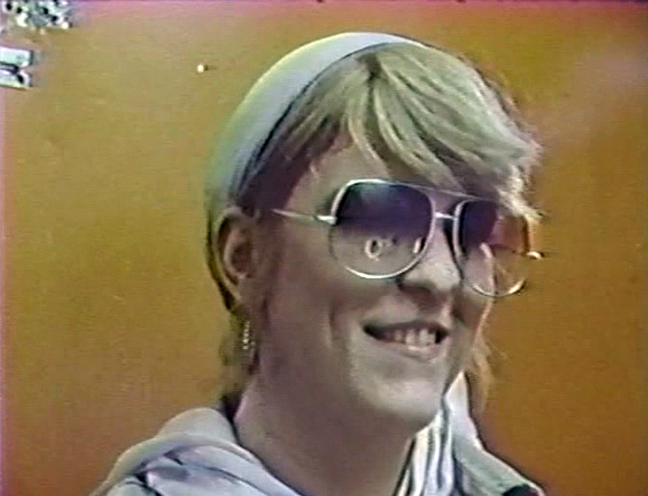

Honey Bee had turned 21 in July 1981. She had inherited Murray’s height, but was heavyset and butch. She was prone to wearing scarves on her head and big sunglasses. She was an easy-going and friendly girl, and liked by all. She hung out with everyone from the maintenance guys to the projectionists. Most of all, she enjoyed being part of the film shoots, especially the Phil Prince ones. She volunteered for everything, made herself busy, and welcomed any tasks that came her way. Phil liked her, and gave her an assistant director credits on ‘The Story of Prunella’ (1982) and ‘Forgive Me, I Have Sinned’ (1983), where she was referred to as ‘Bumble Bee’ thanks to her industrious nature.

Murray Offen’s daughter Honey Bee joins the family business

Murray Offen’s daughter Honey Bee joins the family business

In Phil’s pseudo-documentary Pain Mania’ (1983), Honey Bee had a role in front of the camera (though a strictly non-sexual one) playing the part of a reporter called ‘Nina Nookie.’ It’s a crude and uncompromising account of the sex shows that took place in the Avon theaters, featuring an assortment of footage of floggings and torture. Despite the nature of the content, looking at the film thirty years later, it’s hard not to smile at Honey Bee’s earnest attempts to interview the sex workers backstage. She giggles as she flubs her lines and asks truly bizarre questions.

Honey Bee in ‘Pain Mania’ in front of the New Paris theater

Honey Bee in ‘Pain Mania’ in front of the New Paris theater

After a while, some people figured out she was Murray’s daughter. They put two and two together, and made five – concluding that she stood to inherit the Avon business. Or at least a big part of the moola that came from it. In some people’s eyes, this made Honey Bee a mark. Certain Avon employees and porn performers approached her for money. At best, they had half-baked business schemes that needed an investor or lender. At worst, Honey Bee was threatened with physical violence if she didn’t cough up.

Honey Bee hadn’t been raised on the streets, and hanging out with the Avon girls and the other transient workers in the theaters came at a cost, when Honey Bee developed a nasty drug habit. Murray and Mickey were worried parents, and encouraged her to move in with Stella at 160 West End Ave, just around the corner from where they lived on Riverside Drive. Stella was stern and firm, but could be caring too, and the hope was that Honey Bee just needed some tough love and a better role model. Perhaps it was just a phase Honey Bee was going through.

None of it worked: Honey Bee died of an overdose in February 1987.

When I raise the topic twenty years later with Stella, it’s clear that some wounds don’t heal.

“Honey Bee’s death was the saddest moment of my life,” Stella says. “She was a happy, sweet, gentle girl, who should never have died so young. I don’t know how it happened. I don’t want to know now. Too much water under the bridge.” Stella signals that she’s ready to change the subject.

I called Brian O’Hara, editor of a number of Avon films for Phil Prince, and cameraman for ‘Pain Mania’ that had featured Honey Bee. I asked him if he remembered her passing. Brian said that that shortly after her death, he’d gotten a call from Stella. She was freaking out, he said. Distraught and crying – most unlike the normally-solid all-business manager. The reason for her call was simple: Stella asked Brian if he had any footage of Honey Bee. Any outtakes of her interviews. Any footage that hadn’t been used. Anything that featured her face.

The request had actually come from Murray and Mickey. They realized they had no home movies of Honey Bee and they desperately wanted something – anything – that would be a record of her now that she was gone. Brian cut a selection of film clips and had them transferred to tape. He took them over to Stella who was hugely grateful. Brian was happy to help, even if he found the experience of consoling grieving parents with footage of interviews from a hardcore S&M porn movie odd.

In speaking to people over the years, a small but alarming number of Honey Bee’s friends suggested that the overdose that killed her was neither self-inflicted nor accidental. The story goes that one of the Avon film actresses, one of the bigger names, had mainlined Honey Bee in retaliation for her having turned down a request for money. These co-workers argued whether the person had meant to kill her, or merely wanted to give her a violent shock to the system by injecting her with drugs. Who knows if the story was merely a myth that had taken hold after being repeated many times, or whether it was the truth?

Some argued that as Honey Bee was long gone, it was irrelevant now.

*

By the mid 1980s, Murray was finding it difficult to maintain the Avon business in the same way.

He was broken by Honey Bee’s passing and stressed with Elliot’s tailspin. To make matters worse, Avon star director Phil Prince had been arrested and thrown in jail for a shooting incident in a West Village ice cream parlor. More and more theaters were shutting down. Cheap, highly addictive crack cocaine had been mass-merchandised, and the cinemas became dangerous playgrounds for addicts. Times just weren’t what they used to be.

Murray and Stella struggled on without Phil, but the film business was in decline. It turns out people just weren’t willing to risk life and limb by venturing into drug-infested theaters to watch George Payne verbally abuse and torture another victim. Sensing a change in the air, Avon had been quick to release their films on home video. They sold well to people who wanted to watch sexual mayhem in the convenience of their own homes, so Murray had another income stream coining profit for the business. But the profits weren’t making up for the losses.

Avon films sell well on home video

Avon films sell well on home video

Murray had had enough, He was now in his 70s, and had good money in the bank. He didn’t need the daily grind. He and Mickey moved down to Miami Beach into an apartment at 5101 Collins Ave., and Murray divided his time between Florida and what was left of his New York empire. Stella soon followed, moving into a condo up the coast in Boynton Beach.

The stage was set for a quiet retirement. Unfortunately for Murray, his nephew Elliot also decided to head south.

*

By now Elliot was collecting disability payments, claiming his fear of germs, inherited from his mother, made him unable to work. But he had a dream. He wanted to open an exercise and nutrition counseling business, inspired by his “personal idol”, Uncle Murray.

So far, so normal. But Elliot’s methods were unconventional: he cross-dressed flamboyantly and handed out flyers on Miami Beach, asking for $95 to provide “unlimited telephonic or personal instruction in terms of diet and exercise.” His ploy attracted more antagonism than clientele, and he was pelted with everything from batteries to banana peels.

Elliot Offen flaunts his wares

Elliot Offen flaunts his wares

The local newspapers spotted a story, and made hay. An article in the Miami New Times in 1994, entitled Body By Joke, painted the bizarre picture:

Elliot Offen, the runner who makes a nightly eighteen-mile trek wearing skimpy, ruffled women’s lingerie, pantyhose, white makeup, red lipstick, and Reeboks causes heads to turn.

By any standard, Offen is unique. An Orthodox Jew who goes to synagogue three times a day and does not run on Friday night or Saturday, Offen has been running in women’s clothes, not only to satisfy what he describes as an urge to “dress as a chick,” but to show off his athletic prowess and “statuesque” body.

“I have showcased myself. I’ve made myself stand out to this whole community,” says Offen. “I thrive on public attention, probably because I had no attention throughout my entire childhood.

Whenever he was interviewed interviewed – and it was happening more and more, Elliot raved about his uncle Murray, who the newspapers quaintly described as “a veteran of the theater business.”

“He knows more about endocrinology than an endocrinologist and more about gastroenterology than a gastroenterologist,” said the proud nephew. “He is my greatest personal idol. Uncle Murray was on a health-kick kind of lifestyle when no one knew how to live a disease-free life without contamination.”

Needless to say, Murray was mortified by Elliot’s activity, and the attention it brought him.

*

By the 1990s, the New York of Murray’s heyday was dead. The locations on which Murray’s empire had been built were gone or disappearing fast.

The New Paris, where it had all begun for Murray in its former incarnation as the Orpheum, was shut down in 1991 by AIDS and civic cleanup efforts. Many of his other theaters had already bitten the dust. The Avon on the Hudson and the Park-Miller had long stopped being Avon locations, and they were followed by the shuttering of the Avon 7, Avon Love and the Doll.

People were moving on too. One by one, Murray’s friends and foes vanished. Chelly Wilson passed away in November 1994 at the age of 85. Murray withdrew quietly. It was a silent and sad anti-climax to a life that had shaped the New York sex business for so long.

Murray died in May 2000.

*

Elliot eventually moved back to Manhattan where he became known as the ‘UES (Upper East Side) Lingerie Jogger’. He ran daily in a variety of extravagantly feminine clothes for several years before being tapped to appear on the Howard Stern show.

Murray Offen’s nephew Elliot frequently found himself at the center of trouble

Murray Offen’s nephew Elliot frequently found himself at the center of trouble

Now known as ‘Elegant’ Elliot Keith Offen, he became a regular, not to mention confrontational, guest on the popular show, where he was known for his quick temper and extensive array of profane insults and catchphrases directed at Howard and his team.

Elliott’s controversial appearances abruptly stopped in 2006 when he ran over an elderly woman with a truck. Stern invited Elliot into the studio to discuss the tragic accident, an interview which ended when Elliot punched a hole in the studio wall. He was banned from the Sirius building after that, and never made another appearance on the show.

Never far from controversy, Elliot most recently made the news again in 2015, resulting in the memorable headline: “Howard Stern cross-dresser attacked in hate crime outside Brooklyn synagogue by man who threatened to cut off his penis.”

*

In 2010, I called Mickey Offen, Murray’s widow.

At first she thought I was with the IRS, which was fitting because I certainly wondered how much money Murray had made – and where it all went.

She was in poor health, and still missed her husband, but was happy to remember the distant days when they had taken over the Orpheum together. It felt like we owned the secrets of New York, she said. She remembered her taxi girls fondly, and spoke of the old Howard Johnsons, full of neon and paneled wood, where she’d meet with potential dancers to discuss what was expected of them. She was well aware of the location’s former history, and had enjoyed running the business in such a venerable venue.

She hadn’t liked being the center of attention when they were arrested, but weathered the storm, learned her lesson and stayed in the shadows after that.

I tell her that she’d put up a strong defense of the taxi-dance business, and had come across as feisty in the newspaper reports.

Mickey laughs. “I’m from the south. I’ll always be a feisty dame.”

Our conversation moved to the present. Mickey had heard that the old Orpheum building had been sold and demolished in 2006 to be replaced by anonymous commercial fashion stores. She wished she’d seen it one final time before the wrecking ball.

After Murray’s passing, Mickey had moved an hour north of Miami to a retirement community in Pompano Beach, near where Stella lived. They kept each other company, two old Jewish women eating the early bird special at the local diner, going to the occasional film, and sitting on the beach chatting away.

People who passed them smiled at the grey-haired, gossipy pair. They looked ancient and innocuous. Two alter cocker bubbas, probably sharing stories about grandchildren or latke recipes.

Looks can be deceiving though. Between them they held innumerable sexual secrets that shaped half a century in New York.

Mickey died in October 2010, and Stella passed in October 2012.

Times passes irrevocably, flying over us, but its shadows remain.

Memories of Murray Offen’s New York

Memories of Murray Offen’s New York

*

On the next Rialto Report, the second part of ‘Avon Films – Journeys into the Dark Heart of XXX’.

*

The Orpheum reminds me of the pay-to-dance dance hall in Stanley Kubrick’s first film, ‘Killer’s Kiss’ from the late fifties. That film also has a few quick shots of Times Square street scenes in black and white outside the dance hall. Kudos to the Rialto team for another engrossing in-depth look at the capitalistic workings of porno’s heyday in NYC, and the enterprising people behind it all. And it’s good to see George looking as intense as ever.

Thank you Mikey!

The best podcast of the Rialto Report.

AW. Bravo

Thank you Louie!

oh boy – huge post…. and i mean that in terms of importance.

this has re-set the baseline for reporting times square.

for years, writer have suggested that the avon chain belonged to chelly wlson….. and now the truth emerges.

i look forward to part 2

I think the myth that Chelly Wilson owned Avon came from Bill Landis, who wrote….

“Chelly Wilson was the ipsissimis of Times Square’s pyramid of pornographic film producers, exhibitors, directors and sex performers. Mrs. Wilson’s left hand man, Murray, ran the Avon chain.”

Undoubtably Landis…I have all the Sleazoid Express issues (at least the ones Bill and Jimmy still had) and he and Michelle Clifford pushed the Chelly story for sure.

Bill Landis was a talented writer, who experienced much of what he writes about first hand.

Historically though, his work is riddled with assumptions and errors and plain made-up nonsense.

Shame, as the reference to Chelley Wilson set researchers back decades.

Agreed. Bill, may he Rest In Peace, was, at least to a degree, living The Part a bit too much. We talked for a while, before he turned on me. Or Michelle had him turn on me. Tragic soul. Maybe that curse Anger put on him really worked. Also tragic that he left Michelle a single mother.

This is the most detailed, informative, well-written, and hysterical account of the NYC porn biz I’ve ever read.

Truly outstanding research and my hats off to you for this impressive work.

We so appreciate it Rob – thank you!

History books need a re-write – The Rialto Report is in the house.!!!!

Love the way you link so many threads together in an amazing peice of writing.

What is left for part 2 after this!?!>

Wait and see Rialto fan – we’re excited to share it with you!

Groundbreaking essential research.

Thank you John!

The only musical cue I think was missing was Tina Turner’s “Private Dancer”!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d4QnalIHlVc

Good call Rick!

Wow, great work. Who knew???? All so behind the scenes.

It’s simply amazing to me that I made some of these films, and just saw the sexy fun and fantasy of it. I must have had blinders on.

You were focused on other things Annie! 🙂

Beyond amazing, RR!

Never seen any of the films, but what a story.

Thank you JWP!

All I can say is, wow! Thank you for a riveting story. It’s hard not to look at this as some sort of made up story, but you help bring these people to light with all of their foils and grace, indeed their dignity. Just wonderful.

We greatly appreciate it Scott!

Small world–The Rialto Report and Elegant Elliott Offen collide. Never thought in a million years those two worlds would meet.

RIIIIGHT?!?!?!?

This is amazing. I had no clue The Elegant One was linked to the adult cinema industry.

HOLY CRAP. Amazing story.

Someone make a film about this. Now. I demand it!

Great job as always.

Thank you!

Great work! Really enjoyed it. Lots of new info uncovered.

We appreciate it Robin!

I loved the Bryant on 42nd St, best JO movie house on the Deuce, best thing about it was that others would jerk you off for free!

This was excellent! Can’t wait for the next installment! Very well done, this should become a full length book.

Peter

..or a documentary.

Thanks Peter!

Seriously brilliant uncovering of so much new information.

And good to see Landis’ belief that Chelly Wilson owned the Avon chain debunked definitively once and for all.

The Deuce has a new hero: the “conductor of a symphony who was standing in the dark”……. Murray Offen.

We appreciate it Ben!

I never thought anything would hurt my eyes more than the Avon films….. until I saw the pictures of Elegant Elliot in drag.

Ouch.

I loved every minute of this.

So glad you did Anon.

This is outstanding journalism.. Incredible, really…

Thanks very much!

Great work, amazingly detailed. When Times Square was the wild west of sleaze.

It’s the gift that keeps on giving.

I’ve just listened to the podcast and was struck by the richness of the many stories that are covered. In fact it’s going to take me a few more listens before I can truly appreciate and take onboard all the details.

However I want to offer you my great thanks for the incredible care and humanity that goes into lengthy works like this. This type of long-form read, made available free of charge and without ads, has clearly taken years to put together.

I am constantly impressed by The Riatlo Report. This is fine work.

Thank you so much Jack – we appreciate your comment.

What an wonderful report about AVON and all activities around. Truly great journalism and highly entertaining too! I cant wait to read part 2! Thank you so much Rialto Report!!!

Thanks to you for taking the time to comment.

Let me second that this has been the best of all the episodes thus far. Incredible research and reporting!

Having viewed the Avon Films – and their amazing trailers early on, – this episode gives me a whole new perspective. Can’t wait for Part 2.

Thank you!

Thanks Derek!

I wondered why they were called Avon. A coincidence? Now I understand.

Incredible work by the Rialto Report.

Thank you Ron!

Fascinating. You guys ought to be teaching a college course on the social history of the urban environment post WWII.

We’re happy sharing the information with the world right here Henry!

From the moment I discovered The Rialto Report three years ago, I have hoped that the day would come when you turned your eagle eyes and hunger for the truth to the Avon films. This is the story I’ve been waiting to read for years, and to be honest, my only worry was that someone else would try to tell it – and inevitably fail.

You haven’t let me down. This is a story that could be in the pages of Vanity Fair or New York magazine. Truly gripping, well written, and expertly researched.

I look forward to the next installment with eager anticipation.

We really appreciate the kind words Richard.

You must get tired of people telling you that you’re doing some of the best journalism on the entire internet …

While the subject matter is bizarre and disturbing, the level of technical incompetence of the Avon films, especially the cheap sets and the clearly drugged-out, barely-able-to-perform performers make them more than a bit farcical, especially in the case of THE TAMING OF REBECCA.

Far more unpleasant and difficult to watch now, of course, are the “porn adjacent” horror movies of the period, like MANIAC, LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT, and CANNIBAL HOLOCAUST, which were directed by or starring people connected to classic golden age New York porn. Perhaps you’ll do a feature on some of those, one of these days.

Anxiously awaiting part 2, and I hope we’ll hear more about Phil Prince, who seems like a real … er … gem.

Thank you so much Natasha!

And I’m guessing that the Orpheum’s tagline of ’50 Beautiful Lonely Hearts to Dance with You!’ was the inspiration for the long running slogan of the Deja Vu strip club chain: ’50 Beautiful Girls… and 3 Ugly Ones’.

Connections, connections.

I can’t add anymore to the compliments here so I’ll pose a question: Who owns the masters to these films, if such things exist, and what is the distribution trail for how they got out when the VHS era began? Oh, I’ll add one more thing, Phil Prince, didn’t he do live shows as well as directing? He seems worthy of a bit more Rialto Report attention.

You keep going one better, Ashley. What a sterling piece of gritty, substantial journalism , and a hugely illuminating look deeper into Avon.

I, too, would love to know the status of the Avon films. Do negs/internegs/prints still exist? Will they ever be transferred to BluRay?

Thank you for your ongoing mission. Easily my favourite corner of the podcast world.

Use of music/transitions is priceless.

WOW!!!! Been waiting for this all my life, i LOVE you guys, thank you soooo much!

Thank you Gary!

Another intriguing journey through a fascinating sub culture ….

Phenomenal episode guys…

Have a great holiday…

Rich…

George Payne is quite a character. Remarkable. If not for his illustrious and controversial career as a porn actor, he could get mainstream work, much like the late Robert Kerman better known as R. Bolla in the industry. He could even do voice acting for video games just with one liners. When it comes to classic adult films, just like they say, you see one, you’ve seen them all, well if you watch in Avon film, I would say I’ve seen them all, and not anymore. The only one I saw was “The Story of Prunella”. Cheap and dirty. Can’t say I enjoyed the film, I was fortunate enough to get through it without shutting it off. To Ashley and April, I always enjoy listening to the RR podcast, especially there’s an episode for me to listen to. 13 years and still going.

Just listened again and I think it should be noted what an amazing writer and narrator Ashley is. The ending of the podcast was such an eloquent expression of nostalgia and loss that it left me feeling gutted. Absolutely remarkable reporting.

Thank you for writing this. I didn’t know this about my Aunt Mickey. I didn’t know Honey Bee died from drugs. We just never talked about it. Mickey took care of her son Juan.